I agree with most of this post, but do want to provide a stronger defense of at least a subtype of tone arguments that I think are important (I think those are not the most frequently deployed type of tone arguments, but they are of a type that I think are important to allow people to make).

Tone arguments are practically always in bad faith. They aren't made by people trying to help an idea be transmitted to and internalized by more others.

To give a very extreme example of the type I am thinking about: Recently I was at an event where I was talking with two of my friends about some big picture stuff in a pretty high context conversation. We were interrupted by another person at the event who walked into the middle of our conversation, said "Fuck You" to me, then stared at me aggressively for about 10 seconds, then insulted me and then said "look, the fact that you can't even defend yourself with a straight face makes it obvious that what I am saying is right", then turned to my friends and explained loudly how I was a horrible person, and left a final "fuck you" before walking away.

The whole interaction left me quite terrified. I managed t...

[EDIT: see the comment thread with Wei Dai, I don't endorse the policing/argument terms as stated in this comment]

I agree that tone policing is not always bad. In particular, enforcement of norms that improve collective epistemology or protect people from violence is justified. And, tone can be epistemically misleading or (as you point out) constitute an implicit threat of violence. (Though, note that threats to people's feelings are not necessarily threats of violence, and also that threats to reputation are not necessarily threats of violence; though, threats to lie about reputation-relevant information are concerning even when not violent). (Note also, different norms are appropriate for different spaces, it's fine to have e.g. parties where people are supposed to validate each other's feelings)

Tone arguments are bad because they claim to be "helping you get more people to listen to you" in a way that doesn't take responsibility for, right then and there, not listening, in a way decision-theoretically correlated with the "other people". (That isn't what happened in the example you described)

I agree that people threatening mob violence is generally a bad thing in discourse. (Threats of mob violence aren't arguments, they're... threats) Such threats used in the place of arguments are a form of sophistry.

It's confusing that "tone argument" (in the OP) links to a Wikipedia article on "tone policing", if they're not supposed to be the same thing.

What is the actual relationship between tone arguments and tone policing? In the OP you wrote:

A tone argument criticizes an argument not for being incorrect, but for having the wrong tone.

From this it seems that tone arguments is the subset of tone policing that is aimed at arguments (as opposed to other forms of speech). But couldn't an argument constitute an implicit threat of violence, and therefore tone arguments could be good sometimes?

It seems like to address habryka's criticism, you're now redefining (or clarifying) "tone argument" to be a subset of the subset of tone policing that is aimed at arguments, namely where the aim of the policing is specifically claimed to be “helping you get more people to listen to you”. If that's the case, it seems good to be explicit about the redefinition/clarification to avoid confusing people even further.

Saying "fuck you" and waiting ten seconds? There's a good chance they were trying to bait you into a reportable offense. That said, you should've used more courage in the moment, and your "friends" should've backed you up. If you find yourself in that situation again, try saying "no you" and improvise from there.

If you find yourself in that situation again, try saying “no you” and improvise from there.

Why take the risk of this escalating into a seriously negative sum outcome? I can imagine the risk being worth it for someone who needs to constantly show others that they can "handle themselves" and won't easily back down from perceived threats and slights. But presumably habryka is not in that kind of social circumstances, so I don't understand your reasoning here.

Why take the risk of this escalating into a seriously negative sum outcome?

Because if someone does that to you (walking up to you and insulting you to your face, apropos of nothing), then the value to them of the situation’s outcome no longer matters to you—or shouldn’t, anyway; this person does not deserve that, not by a long shot.

And so the “negative sum” consideration is irrelevant. There’s no “sum” to consider, only the value to you. And to you, the situation is already strongly negative.

Now, it is possible that you could make it more negative, for yourself. Possible… but not likely. And even if you do, if you simultaneously succeed at making it much more negative for your opponent, you have nonetheless improved your own outcome (for what I hope are obvious game-theoretic reasons).

Aren’t you, after all, simply asking “why retaliate against attacks, even when doing so is not required to stop that particular attack”? All I can say to that is “read Schelling”…

Fun tends to be highly personal, for example some people find free soloing fun, and others find it terrifying. Some people enjoy strategy games and others much prefer action games. So it seems surprising that you'd give an unconditional "should have" criticism/advice based on what you think is fun. I mean, you wouldn't say to someone, "you should not have used safety equipment during that climb." At most you'd say, "you should try not using safety equipment next time and see if that's more fun for you."

I think NVC has the thing where, if it's used well, it's subtle enough that you don't necessarily recognize it as NVC.

I tend to (or at least try to remember to) draw on NVC a lot in conversation about emotionally fraught topics, but it's hard for me to recall the specifics of my wording afterwards, and they often include a lot of private context. But here's an old example which I picked because it happened in a public thread and because I remember being explicitly guided by NVC principles while writing my response.

As context, I had shared a link to an SSC post talking about EA on my Facebook page, and some people were vocally critical of its implicit premises (e.g. utilitarianism). The conversation got a somewhat heated tone and veered into, among other things, the effectiveness of non-EA/non-utilitarian-motivated volunteer work. I ended making some rather critical comments in return, which led to the following exchange:

The other person: Kaj, I also find you to be rather condescending (and probably, privileged) when talking about volunteer work. Perhaps you just don't realize how large a part volunteers play in doing the work that supposedly belongs to the state, but isn't being taken care of. And your suggestion that by volunteering you mainly get to feel better about yoursel...

The problem with Calvinism is that it does not allow for improvement. We are (Calvin and Calvinists say) utterly depraved, and powerless to do anything to raise ourselves up from the abyss of sin by so much as the thickness of a hair. We can never be less wrong. Only by the external bestowal of divine grace can we be saved, grace which we are utterly undeserving of and are powerless to earn by any effort of our own. And this divine grace is not bestowed on all, only upon some, the elect, predetermined from the very beginning of Creation.

Calvinism resembles abusive parenting more than any sort of ethical principle.

Eliezer has written of a similar concept in Judaism:

Each year on Yom Kippur, an Orthodox Jew recites a litany which begins Ashamnu, bagadnu, gazalnu, dibarnu dofi, and goes on through the entire Hebrew alphabet: We have acted shamefully, we have betrayed, we have stolen, we have slandered . . .

As you pronounce each word, you strike yourself over the heart in penitence. There’s no exemption whereby, if you manage to go without stealing all year long, you can skip the word gazalnu and strike yourself one less time. That would violate the community spirit of Yom Kippur, which...

I've heard of a similar superstition in Christendom, that if for a single day, no-one sinned, that would bring about the Second Coming. The difference between either of these and a total lack of hope is rounding error.

The alternative is just this: there is work to be done — do it. When the work can be done better — do it better. When you can help others work better — help them to work better.

Forget about a hypothetical absolute pinnacle of good, and berating yourself and everyone else for any failure to reach it. It is like complaining, after the first step of a journey of 10,000 miles, that you aren't there yet.

I quoted Spurgeon as a striking example of pure, stark Calvinism. But to me his writings are lunatic ravings. In fairness, some of the quotes on the spurgeon quotes site are more humane. But Calvinism, secular or religious, is an obvious failure mode. DO NOT DO OBVIOUS FAILURE MODES.

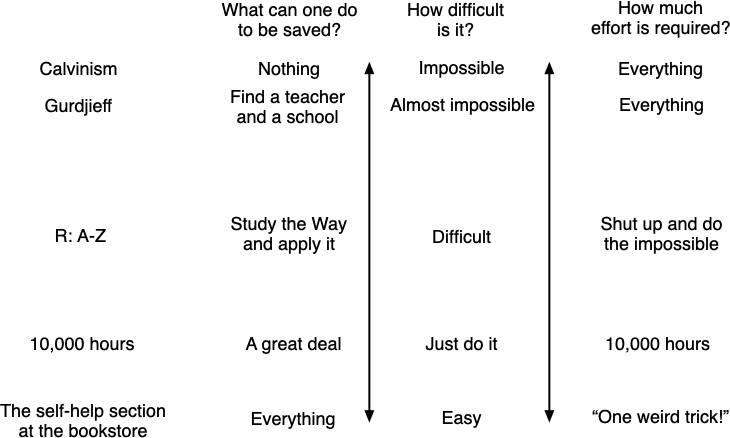

Considering this more widely, here's a diagram I came up with. (Thanks to Raemon for advice on embedding images.)

(Please let me know if you do not see an image above. There might be a setting on my web site that blocks embedding.) (ETA: minor changes to image.)

What if it isn’t actually possible to be “not racist” or otherwise “a good person”, at least on short timescales? What if almost every person’s behavior is morally depraved a lot of the time (according to their standards of what behavior makes someone a “good person”)? What if there are bad things that are your fault? What would be the right thing to do, then?

This paragraph (and the entire concept described in this last part of the post) is—if the words therein are taken to have their usual meanings—inherently self-contradictory.

If it’s not possible for you to do something, then it cannot possibly be your fault that you don’t do that thing. (“Ought implies can” is the classic formulation of this idea.)

Rejecting “ought implies can” turns the concepts of fault, good, etc., into parodies of themselves, and morality into nonsense. If morality isn’t about how to make the right choices, then what could it be about? Whatever that thing is, it’s not morality. If you say that according to your “morality”, I can’t be “good”, on account of there being no “right” choice available to me, my answer is: clearly, whatever you mean by “good” and “right” and “morality” isn’t what I mean by those

I'm going to clarify what I mean by "what if it's not possible to be a good person?"

Most people have a confused notion of what a "good person" is. According to this notion, being a "good person" requires having properties X, Y, and Z. Well, it turns out that no one, or nearly no one, has properties X&Y&Z, and also couldn't achieve them quickly even with effort. Therefore, no one is a "good person" by that definition.

If you apply moral philosophy to this, you can find (as you point out) that this definition of "good person" is rather useless, as it isn't even actionable. Therefore, the notion should either be amended or discarded. However, to realize this, you have to first realize that no one has properties X&Y&Z. And, to someone who accepts this notion of "good person", this is going to feel, from the inside, like no one is a good person.

Therefore, it's useful to ask people who have this kind of confused notion of "good person" to imagine the hypothetical where no one is a good person. Imagining such a hypothetical can lead them to refine their moral intuitions.

[EDIT: I also want to clarify "some behavior is unethical and also hard to stop". What I mean her

being a "good person" requires having properties X, Y, and Z. Well, it turns out that no one, or nearly no one, has properties X&Y&Z, and also couldn't achieve them quickly even with effort. Therefore, no one is a "good person" by that definition.

Some examples of varying flavour, to see if I've understood:

Being a good person means not being racist, *but* being racist involves unconscious components (which Susan has limited control over because they are below conscious awareness) and structural components (which Susan has limited control over because she is not a world dictator). Therefore Susan is racist, therefore not good.

Being a good person means not exploiting other people abusively, *but* large parts of the world economy rely on exploiting people, and Bob, so long as he lives and breathes, cannot help passively exploiting people, so he cannot be good.

Alice likes to think of herself as a good person, but according to Robin Hanson, most of what she is doing turns out to be signalling. Alice is dismayed that she is a much shallower and more egotistical person than she had previously imagined.

But the problem with these criteria isn’t that they’re unsatisfiable! The problem is that they are subverted by malicious actors, who use equivocation (plus cache invalidation lag) as a sort of ‘exploit’ on people’s sense of morality. Consider:

Everyone agrees that being a good person means not being racist… if by that is meant “not knowingly behaving in a racist way”, “treating people equally regardless of race”, etc. But along come the equivocators, who declare that actually, “being racist involves unconscious and structural components”; and because people tend to be bad at keeping track of these sorts of equivocations, and their epistemic consequences, they still believe that being a good person means not being racist; but in combination with this new definition of “racist” (which was not operative when that initial belief was constructed), they are now faced with this “no one is a good person” conclusion, which is the result of an exploit.

Everyone agrees that being a good person means not exploiting people abusively… if by that is meant “not betraying trusts, not personally choosing to abuse anyone, not knowingly participating in abusive dynamics if you can easily avoid it”, etc...

"Feeling guilty/ashamed, then lashing out in order to feel better" is a good example of an exile/protector dynamic. It may be possible to reduce the strength of such reactions through an intellectual argument, as you seem to suggest yourself to have done. But as Ruby suggested, the underlying insecurity causing the protector response is likely to be related to some fear around social rejection, in which case working on the level of intellectual concepts may be insufficient for changing the responses.

I suspect that the "nobody is good" move, when it works, acts on the level of self-concept editing, changing your concepts so as to redefine the "evil" act to no longer be evidence about you being evil. But based on my own experience, this move only works to heal the underlying insecurity when your brain considers the update to be true - which is to say, when it perceives the "evil act" to be something which your social environment will no longer judge you harshly for, allowing the behavior to update. If this seems false, or the underlying insecurity is based on a too strong of a trauma, then one may need to do more emotional kind of work in ord...

It might be worth separating self-consciousness (awareness of how your self looks from within) from face-consciousness (awareness of how your self looks from outside). Self-consciousness is clearly useful as a cheap proxy for face-consciousness, and so we develop a strong drive to be able to see ourselves as good in order for others to do so as well. We see the difference between this separation and being a good person being only a social concept (suggested by Ruby) by considering something like the events in "Self-consciousness in social justice" with only two participants: then there is no need to defend face against others, but people will still strive for a self-serving narrative.

Correct me if I'm wrong: you seem more worried about self-consciousness and the way it pushes people to not only act performatively, but also limits their ability to see their performance as a performance causing real damage to their epistemics.

The phenomenon of people changing the subject to "Who is, or is not, Bad" is a very serious problem that prevents us from making intellectual progress on topics other than the question of who is Bad. (And actually, that topic as well.) It can be a serious problem even if the people who do it are not Bad!

I've been paying more attention to this reaction over the last few days since reading this post, and realize that its' often a bit different than "You're calling this bad, I've done it, I don't want to be a bad person, so I want to defend this as good."

Oftentimes the actual reaction is something like "You're calling this bad, and I've done it and don't believe its' bad. If I let this slide, I'm letting you set a precedent for calling my acceptable behavior bad, and I can't do that."...

I imagine that Susan's position is complicated, because in the social justice framework, in most interactions she is considered the less-privileged one, and then suddenly in a few of them she becomes the more-privileged one. And in different positions, different behavior is expected. Which, I suppose, is emotionally difficult, even if intellectually the person accepts the idea of intersectionality.

If in most situations, using tears is the winning strategy, it will be difficult to avoid crying when it suddenly becomes inappropriate for reasons invisibl...

however, tone arguments aren't about epistemic norms, they're about people's feelings

One interesting idea here is that people's feelings are actually based on their beliefs (this is for instance one of the main ideas behind CBT, Focusing, and Internal Double Crux).

If I make people feel bad about being able to express certain parts of themselves, I'm creating an epistemic environment where there are certain beliefs they feel less comfortable sharing. The steelmanned tone argument is "By not being polite, you're creating...

The only thing left to do is to steer in the right direction: make things around you better instead of worse, based on your intrinsically motivating discernment of what is better/worse. Don't try to be a good person, just try to make nicer things happen. And get more foresight, perspective, and cooperation as you go, so you can participate in steering bigger things on longer timescales using more information.

FWIW, this is roughly my viewpoint.

I don't think being a good person is a concept that is really that meaningful. Meanwhile, many of the sys...

I don't think being a good person is a concept that is really that meaningful.

My not-terribly-examined model is that good person is a social concept masquerading as a moral one. Human morality evolved for social reasons to service social purposes [citation needed]. Under this model, when someone is anxious about being a good person, their anxiety is really about their acceptance by others, i.e. good = has met the group's standards for approval and inclusion.

If this model is correct, then saying that being a good person is not a meaningful moral concept could be interpreted (consciously or otherwise) by some listeners to mean "there is no standard you can meet which means you have gained society's approval". Which is probably damned scary if you're anxious about that kind of thing.

My quick thoughts on the implications is something like maybe it's good to generally dissolve good person as a moral concept and then consciously factor out the things you do to gain acceptance within groups (according to their morality) from the actions you take because you're trying to optimize for your own personally-held morality/virtues/value.

> It's clear why tone arguments are epistemically invalid. If someone says X, then X's truth value is independent of their tone, so talking about their tone is changing the subject.

If tone is independent of truth then it should be possible to make a truth-compliant and tone-compliant comment. That is the thing should be bad even if you sugarcoat it. you don't need ot be anti-tone to be pro-truth althought it is harder to be compliant on both and people typically need to spread their skills over those goods. There is the kind of problem...

I definitely notice this pattern of "feeling like the thing someone is pointing at is them pointing at me. then having to defend it to defend myself."

I move that's similar to the Calvanism concept that I've done (but makes me feel less like shit) is something like forgiving myself for making mistakes, and realizing that my mistakes don't define me. Thus when someone points at something that feels like one of my mistakes, I can see that as them pointing at the mistake, instead of me.

This is all a framing game of course, the Calvini...

I think I see a motte and bailey around what it means to be a good person. Notice at the beginning of the post, we've got statements like

Anita reassured Susan that her comments were not directed at her personally

...

they spent the duration of the meeting consoling Susan, reassuring her that she was not at fault

And by the end, we've got statements like

it's quite hard to actually stop participating in racism... In societies with structural racism, ethical behavior requires skillfully and consciously reducing harm

...

almost every person's b...

steer in the right direction: make things around you better instead of worse, based on your intrinsically motivating discernment ... try to make nicer things happen. And get more foresight, perspective, and cooperation as you go, so you can participate in steering bigger things on longer timescales using more information.

This seems kind of like... be a good person, or possibly be good, or do good. And I can't square it with:

accept that you are irredeemably evil

If you're irredeemably evil, your discernment is not to be trusted and your efforts ar...

Is jessicata writing as if being a good person implies being thoroughly good in all respects, incapable of evil, perhaps incapable of serious error, perhaps single-handedly capable of lifting an entire society's ethical standing? That's a very tall order. I don't think that's what "good person" means. I don't think that's a reasonable standard to hold anyone to .

I think this is in fact the belief of Calvinism though. Have you lied? Then you're a liar. Have you acted out of jealousy? Then you're a jealous person. I think for a certain class of people this is obviously the wrong move to make, they'll descend into self loathing.

For another group of people, this is powerful though. I think this is the intuition behind AA "Hi I'm Matt, and I'm an Alcoholic." Once I stop running from the fact that its' in my very nature to want alcohol, I can start consciously working to make the fact that I am an alcoholic have less impact on myself and others (by putting myself in situations that make it easier to choose not to drink, noticing I have to expend willpower when around alcohol, etc). I don't have wa...

Here's a pattern that shows up again and again in discourse:

A: This thing that's happening is bad.

B: Are you saying I'm a bad person for participating in this? How mean of you! I'm not a bad person, I've done X, Y, and Z!

It isn't always this explicit; I'll discuss more concrete instances in order to clarify. The important thing to realize is that A is pointing at a concrete problem (and likely one that is concretely affecting them), and B is changing the subject to be about B's own self-consciousness. Self-consciousness wants to make everything about itself; when some topic is being discussed that has implications related to people's self-images, the conversation frequently gets redirected to be about these self-images, rather than the concrete issue. Thus, problems don't get discussed or solved; everything is redirected to being about maintaining people's self-images.

Tone arguments

A tone argument criticizes an argument not for being incorrect, but for having the wrong tone. Common phrases used in tone arguments are: "More people would listen to you if...", "you should try being more polite", etc.

It's clear why tone arguments are epistemically invalid. If someone says X, then X's truth value is independent of their tone, so talking about their tone is changing the subject. (Now, if someone is saying X in a way that breaks epistemic discourse norms, then defending such norms is epistemically sensible; however, tone arguments aren't about epistemic norms, they're about people's feelings).

Tone arguments are about people protecting their self-images when they or a group they are part of (or a person/group they sympathize with) is criticized. When a tone argument is made, the conversation is no longer about the original topic, it's about how talking about the topic in certain ways makes people feel ashamed/guilty. Tone arguments are a key way self-consciousness makes everything about itself.

Tone arguments are practically always in bad faith. They aren't made by people trying to help an idea be transmitted to and internalized by more others. They're made by people who want their self-images to be protected. Protecting one's self-image from the truth, by re-directing attention away from the epistemic object level, is acting in bad faith.

Self-consciousness in social justice

A documented phenomenon in social justice is "white women's tears". Here's a case study (emphasis mine):

The key relevance of this case study is that, while the conversation was originally about the issue of student community needs, it became about Susan's self-image. Susan made everything about her own self-image, ensuring that the actual concrete issue (that her office was not supporting the racial community) was not discussed or solved.

Shooting the messenger

In addition to crying, Susan also shot the messenger, by complaining about Anita to both her and Anita's supervisors. This makes sense as ego-protective behavior: if she wants to maintain a certain self-image, she wants to discourage being presented with information that challenges it, and also wants to "one-up" the person who challenged her self-image, by harming that person's image (so Anita does not end up looking better than Susan does).

Shooting the messenger is an ancient tactic, deployed especially by powerful people to silence providers of information that challenges their self-image. Shooting the messenger is asking to be lied to, using force. Obviously, if the powerful person actually wants information, this tactic is counterproductive, hence the standard advice to not shoot the messenger.

Self-consciousness as privilege defense

It's notable that, in the cases discussed so far, self-consciousness is more often a behavior of the privileged and powerful, rather than the disprivileged and powerless. This, of course, isn't a hard-and-fast rule, but there certainly seems to be a relation. Why is that?

Part of this is that the less-privileged often can't get away with redirecting conversations by making everything about their self-image. People's sympathies are more often with the privileged.

Another aspect is that privilege is largely about being rewarded for one's identity, rather than one's works. If you have no privilege, you have to actually do something concretely effective to be rewarded, like cleaning. Whereas, privileged people, almost by definition, get rewarded "for no reason" other than their identity.

Maintenance of a self-image makes less sense as an individual behavior than as a collective behavior. The phenomenon of bullshit jobs implies that much of the "economy" is performative, rather than about value-creation. While almost everyone can pretend to work, some people are better at it than others. The best people at such pretending are those who look the part, and who maintain the act. That is: privileged people who maintain their self-images, and who tie their self-images to their collective, as Susan did. (And, to the extent that e.g. school "prepares people for real workplaces", it trains such behavior.)

Redirection away from the object level isn't merely about defending self-image; it has the effect of causing issues not to be discussed, and problems not to be solved. Such effects maintain the local power system. And so, power systems encourage people to tie their self-images with the power system, resulting in self-consciousness acting as a defense of the power system.

Note that, while less-privileged people do often respond negatively to criticism from more-privileged people, such responses are more likely to be based in fear/anger rather than guilt/shame.

Stop trying to be a good person

At the root of this issue is the desire to maintain a narrative of being a "good person". Susan responded to the criticism of her office by listing out reasons why she was a "good person" who was against racial discrimination.

While Anita wasn't actually accusing Susan of racist behavior, it is, empirically, likely that some of Susan's behavior is racist, as implicit racism is pervasive (and, indeed, Susan silenced a woman of color speaking on race). Susan's implicit belief is that there is such a thing as "not being racist", and that one gets there by passing some threshold of being nice to marginalized racial groups. But, since racism is a structural issue, it's quite hard to actually stop participating in racism, without going and living in the woods somewhere. In societies with structural racism, ethical behavior requires skillfully and consciously reducing harm given the fact that one is a participant in racism, rather than washing one's hands of the problem.

What if it isn't actually possible to be "not racist" or otherwise "a good person", at least on short timescales? What if almost every person's behavior is morally depraved a lot of the time (according to their standards of what behavior makes someone a "good person")? What if there are bad things that are your fault? What would be the right thing to do, then?

Calvinism has a theological doctrine of total depravity, according to which every person is utterly unable to stop committing evil, to obey God, or to accept salvation when it is offered. While I am not a Calvinist, I appreciate this teaching, because quite a lot of human behavior is simultaneously unethical and hard to stop, and because accepting this can get people to stop chasing the ideal of being a "good person".

If you accept that you are irredeemably evil (with respect to your current idea of a good person), then there is no use in feeling self-conscious or in blocking information coming to you that implies your behavior is harmful. The only thing left to do is to steer in the right direction: make things around you better instead of worse, based on your intrinsically motivating discernment of what is better/worse. Don't try to be a good person, just try to make nicer things happen. And get more foresight, perspective, and cooperation as you go, so you can participate in steering bigger things on longer timescales using more information.

Paradoxically, in accepting that one is irredeemably evil, one can start accepting information and steering in the right direction, thus developing merit, and becoming a better person, though still not "good" in the original sense. (This, I know from personal experience)

(See also: What's your type: Identity and its Discontents; Blame games; Bad intent is a disposition, not a feeling)