Funny how I find myself agreeing with everything except for the last paragraph, which I would replace with something like: "if this is the best evidence you can get, maybe it's time to admit that you have no evidence".

I mean, in a universe where Hitchens actually defended waterboarding (and it was a topic important enough for him that he actually tried it), we would expect to find stronger evidence than "one blogger said so" and "it makes a good story". Like, he would actually mention it somewhere in writing or in an interview.

It can be shockingly difficult to track down stuff like this. Even the most high-profile magazines like Time or Newsweek can be hard to get a copy of if you aren't in exactly the right place or if they happen to have not digitized a particular range or your citation isn't exactly right. Television is even worse. Archives of somewhere like CNN are... hard. If you know someone said something at exactly 12:11PM on 15 September 2004 on CNN, on what was perhaps the most watched & influential TV channel in the world, you may seriously struggle to get it if it's not already conveniently excerpted from fourth-hand copies of copies of copies on YouTube.

(This reminds me of a BBC TV documentary on cats and life in cat colonies that I wanted to watch back in 2018. It was a high-profile documentary, even published as a book, and I wanted to watch it because it apparently covered parts that the book did not. After a bunch of searching, I concluded that I had exactly 2 options for accessing it at the time: I could either drive several hundred miles to an obscure library in North Carolina that still had one of the only VHS tapes in the world according to WorldCat, and hope that it worked, and maybe bring along a VHS player just in case; or I could fly to London, and submit a request in writing to the BBC archives to be allowed to watch it - and naturally, I would be strictly forbidden from making a copy or taking any photos of it etc. Meanwhile, the book was a few clicks & $13 to scan... I scanned the book. I have not seen the documentary.)

I recall reading a few months ago an enlightening article on Jon Stewart in the 2000s: why could Stewart marshal so many devastating clips of people saying stuff on TV? Because old stuff on TV disappeared the instant it was broadcast unless someone made a point then and there of videotaping it and making it 'go viral'. Otherwise, it vanished without a trace, as if it were an opium dream, with any copy buried deep in the TV network's vaults.* Technically, it still existed, but it was unfindable, like the ending of Raiders of the Lost Ark. (Sort of like social media: if you don't note down something right now, you may never refind it, even assuming it's not deleted or anything.) So people spoke freely and never worried about old clips resurfacing. But Stewart invested in researchers and paying for access to archives, and pulling up the newly-digitized records to take down guests or subjects.

I imagine there will be similar issues in trying to understand 2010--2030 streaming and Tiktok culture. In theory, it should all be super-legible and everything should be able to be immaculately cited... In practice, you're quickly reduced to rumors of rumors and you know more about the Roman Empire millennia ago than some events beheld by millions on streams just years ago. (AI may be able to help by bruteforce searching gigantic corpuses for the kernel of truth behind the garbled versions which become the standard account, but that won't help in many cases because you won't have the video to analyze - most streaming video, if it was saved at all, is going to be deleted at the first opportunity because video is gigantic & expensive to store. A single streamer could easily be generating tens of terabytes.)

* Itself far from guaranteed. You may know about the BBC Dr Who episodes and other lost TV broadcasts, but this is endemic. Hence https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marion_Stokes

This is one technical point that younger people are often amazed to hear, that for a long time the overwhelming majority of TV broadcast was perfectly ephemeral, producing no records at all. Not just that the original copies were lost or never digitised or impossible to track down or whatever, but that nothing of the sort ever existed. The technology for capturing, broadcasting, and displaying a TV signal is so much easier than the tech for recording one, that there were several decades when the only recordings of TV came from someone setting up a literal film camera pointed at a TV and capturing the screen on photographic film, and that didn't happen much.

(This also meant that old TV was amazingly low latency. The camera sensor scanned through, producing the signal, which went through some analog circuitry and straight onto the air, into the circuitry of your TV and right onto the screen. The scanning of the electron beam across the screen was synchronised with the scanning of the camera sensor. At no point was even a single frame stored - I need to check the numbers but I think if you were close to the TV station, you're looking at the top of the frame before the bottom of the frame is even captured by the camera)

I think you are vastly overestimating the 2001-2010 internet's ability to preserve and catalog evidence.

I would like to add a small element of purely anecdotal evidence to this debate as an avid follower of the "warblogs" and discussions at the time which is slightly different from the "he was pro torture before he was against it" take in your post. My general understanding is that Hitchens was always against "torture" (disagree with Nance's take on this) but there was both a legal and moral debate about water boarding qualifying as torture. For example see this NPR story from 2014: https://www.npr.org/2014/01/07/260155065/cia-lawyer-waterboarding-wasnt-torture-then-and-isnt-torture-now

Hitchens decided to answer the question for himself and came firmly down on the "it is torture and therefore wrong" side of the debate afterwards. He was initially wrong but continued to be intellectually consistent throughout.

Was this post significantly edited? Because this seems to be exactly the take in the post from the start:

because he thought it wasn't bad enough to be considered torture. Then he had it tried on himself, and changed his mind, coming to believe it is torture and should not be performed.

to the end

This is supported by Malcom's claim that Hitchens was "a proponent of torture", which is clearly false going by Christopher's public articles on the subject. The question is only over whether Hitchens considered waterboarding to be a form of torture, and therefore permissible or not, which Malcolm seems to have not understood.

I kind of love how this post is very very narrow, and very very specific, and about a topic that everyone was mind-killed on in the late aughties, but which very few people are mind-killed on in modern times.

It feels like a calibration exercise!

(Also, I wrote a LOT of words on related issues, and what I think this might be a calibration exercise for ...that I've edited out since it was a big and important topic, and would have taken a long time to edit into something usefully readable.)

It is safe and easy to say: I appreciate the scholarship and care that was taken to figure things out here, and to highlight how rare it is for people to understand the specific subquestion, and not conflate subquestions with larger nearby issues, and (without doing any original research or even clicking through to read most of the links) I find the conclusion and confidence level reasonably convincing.

On mechanistic psychology priors (given that no smoking guns were found here) the thing I would expect is that Hitchens spent some time thinking that water boarding wasn't really brutal or terrible torture that should be illegal... (maybe he published something that is hard to find now and felt guilt about that, or maybe he just had private opinions) and then he probably did some research on it and at some point changed his mind in private, and then he might have tried to experience it as a way of creating credibility using a story that would echo in history?

That is, I suspect the direct personal experience didn't cause the update.

I suspect he intellectually suspected what was probably true, and then gathered personally expensive evidence that confirmed his intellectual suspicions for the sake of how the evidence gathering method would play in stories about his take on the topic.

Curated. I appreciated reading this attempt to actually get to the bottom of a simple, widely popularized narrative. It's a helpful datapoint about how reliable narratives are that are spread around our civilization, and how much work is actually involved in checking what actually happened.

That's a great observation, I've added a [comment](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Waterboarding#Citation_needed) in the Talk section for this wikipedia article that there's a missing [citation needed] on that claim about Hitchens's beliefs.

There's a popular story that goes like this: Christopher Hitchens used to be in favor of the US waterboarding terrorists because he though it's wasn't bad enough to be torture.. Then he had it tried on himself, and changed his mind, coming to believe it isn't torture.

though -> thought

it's wasn't -> it wasn't

torture.. -> torture... (ellipses have three dots)

it isn't torture -> it is torture

...I had never thought to question this story, despite it being the primary example I think of when looking for evidence people can change. (Not a formal argument, but a repeated thought experiment)

How many other points like this do I assume I know without the proper research...this is quite the humbling shocker.

Y'all in the comments are epic btw. It's like an extension of the post. I almost feel like this comment only muddies the waters. I have a lot of growing to do.

Hitchens wanted to make a discrimination between "harsh interrogation" and "torture" in a discussion about the CIA on Slate. It's not that he was ever in favor of waterboarding, but that he found it defensible in contrast to what he (initially) considered frank torture. His position was strongly inferred and his agreement to be water-boarded was a test of the binary distinction. He wanted to be able to support the idea that the US was not actually torturing people.

I would find very loud, obnoxious music over an extended period, prolonged sleep deprivation and forced body positions to be torturous. Hitchens, at least initially, would argue they are "harsh interrogation." I think his eventual conclusion is that it's a false binary, though he hedged on that too, by implying in his conclusion that the concept of torture may be flawed.

How would you define torture?

I think something that is missing in the perspective is that, rather than pro or contra, permissible or non-permissible torture, the war on terror might have overridden this in his mind; a greater evil to possibly justify a smaller one. In my memory, from multiple debate appearances, Hitchens was a bit or reasonably supportive of Guantanamo Bay (and thus of a smaller evil to avert a larger one) but also tried to arrive at some reasonable middle position, while the topic was (understandably) very polarizing. It is possible to be against torture, but still be open to considering exceptions.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2025. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

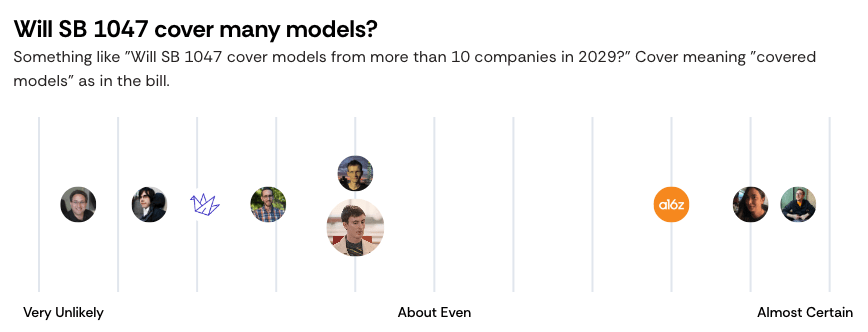

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

Still, when several individually-questionable pieces of evidence are pointing in one direction, and nothing in particular is pointing in the other, that seems like the correct conclusion. I think the story is probably true.

…Huh? The entire rest of the post gave me the exact opposite impression. It sounds like most of the evidence points to the story being false, while hardly anything points to the story being true. Did I miss something?

I think I explain this in the last section? There are several statements he makes that at least imply he doesn't consider it torture, and I couldn't find any with the opposite implication.

I wouldn't assume that Hitchen's writings are a complete record of his views. I remember him being a regular (and fiery!) TV guest during this period, often arguing in defense of military intervention on the basis that radical Islam is an evil worth fighting against. It's possible that he argued in favor of waterboarding in one of these many appearances.

Yes, I did watch some of his interviews on related subjects, but couldn't find any relevant statements one way or the other. But I couldn't watch all that many; as Gwern points out above, many were probably not recorded.

There's a popular story that goes like this: Christopher Hitchens used to be in favor of the US waterboarding terrorists because he thought it wasn't bad enough to be considered torture. Then he had it tried on himself, and changed his mind, coming to believe it is torture and should not be performed.

(Context for those unfamiliar: in the ~decade following 9/11, the US engaged in a lot of... questionable behavior to prosecute the war on terror, and there was a big debate on whether waterboarding should be permitted. Many other public figures also volunteered to undergo the procedure as a part of this public debate; most notably Sean Hannity, who was an outspoken proponent of waterboarding, yet welched on his offer and never tried it himself.)

This story intrigued me because it's popular among both Hitchens' fans and his detractors. His fans use it as an example of his intellectual honesty and willingness to undergo significant personal costs in order to have accurate beliefs and improve the world. His detractors use it to argue that he's self-centered and unempathetic, only coming to care about a bad thing that's happening to others after it happens to him.

But is the story actually true? Usually when there are two sides to an issue, one side will have an incentive to fact-check any false claims that the other side makes. An impartial observer can then look at the messaging from both sides to discover any flaws in the other. But if a particular story is convenient for both groups, then neither has any incentive to debunk it.

I became suspicious when I tried going to the source of this story to see what Hitchens had written about waterboarding prior to his 2008 experiment, and consistently found these leads to evaporate.

The part about him having it tried on himself and finding it tortureous is certainly true. He reported this himself in his Vanity Fair article Believe me, It's Torture.

But what about before that? Did he ever think it wasn't torture?

His article on the subject doesn't make any mention of changing his mind, and it perhaps lightly implies that he always had these beliefs. He says, for example:

In a video interview he gave about a year later, he said:

The loudest people on the internet about this were... not promising. Shortly after the Vanity Fair article, the ACLU released an article titled "Christopher Hitchens Admits Waterboarding is Torture", saying:

But they provide no source for this claim.

As I write this, Wikipedia says:

No source is provided for this either.

Yet it's repeated everywhere. The top comments on the Youtube video. Highly upvoted Reddit posts. Etc.

Sources for any of these claims were quite scant. Many people cited "sources" that, upon me actually reading them, had nothing to do with the claim. Often these "sources" were themselves just some opinion piece from a Hitchens-disliker themselves spreading the rumor with no further sources of their own.

Frankly, many of these people seemed to have extremely poor reading/listening comprehension. For example, christopherhitchens.net affirms the story that he changed his mind from "not torture and morally permissible" to "torture and unacceptable". I reached out to the owner to ask for a source, and they told me to watch his Vanity Fair video, saying:

This A) contradicts their own website, now claiming that he never changed his mind at all, and B), it is false that the video includes anything like that. The only statement he makes in that video that bears any relation to his prior beliefs is:

Not particularly enlightening.

I wasn't the first to have this concern. On the Christopher Hitchens subreddit, one user made a post asking for evidence that he had ever believed waterboarding to be acceptable.

Several comments ignored the question entirely and rambled on about unrelated tangents. One commenter said Hitchens had been more explicit about his support for waterboarding in TV interviews, but did not say which one. (I spent quite a while searching and was unable to find any such interview posted online.) Several other comments claimed that the story was false, and he was always opposed to waterboarding. But none of them provided a source for that claim either! Infuriating.

Ultimately, I could find three articles that Christopher Hitchens wrote prior to the Vanity Fair experiment that people cited in support of this story.

In A War to Be Proud of:

In Abolish the CIA:

In Confessions of a Dangerous Mind:

The first quote from A War to Be Proud of seems completely irrelevant to me and I don't understand why anyone would cite it as supporting evidence. Believing that conditions got better is entirely compatible with waterboarding being torture. (It could be less bad than other forms, or occur less frequently. And Hitchens agreed that more traditional torture was happening there anyway, so his statement must include those too.)

However the other two do paint a picture that is generally in accordance with the story. He describes waterboarding as "rough interrogation", and while this is not technically at odds with it being torture (torture seems like the roughest form of interrogation there is), it does seem like a euphemism that was likely chosen to set waterboarding apart from other forms of torture.

Additionally, in A Moral Chernobyl, Hitchens comes out strongly against the US torturing people. Combined with his support for waterboarding in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, this logically implies that he must believe them to be mutually exclusive.

Still, this is all just inference. Some of those articles were written years apart, so his beliefs could have changed in between, rendering derivations from combinations of those articles invalid. So to be sure, I tried reaching out to people who knew him personally.

I first reached out to Vanity Fair to ask why they had made the offer to Christopher in the first place. Unfortunately they did not respond. I tried contacting Graydon Carter, the Vanity Fair editor-in-chief who proposed the story, via two of his personal email addresses, but he didn't respond either.

I did get a reply from Christopher's brother Peter Hitchens, but it was unhelpful. He and Christopher were somewhat estranged and Peter didn't recall any discussions about this point in particular, saying only:

I reached out to one or two other of his personal friends (those for whom I could find contact information), but got no reply. The only seriously useful lead I got was from Malcolm Nance, a military officer whom Christopher Hitchens mentioned discussing the issue with in his Vanity Fair article.

Nance was an outspoken opponent of waterboarding, and stated on Twitter that Hitchens had first reached out to him to get himself waterboarded as a part of their discussions on the subject. (Nance declined, so Hitchens went with the other team seen in the video.)

Malcolm has a Substack blog and I was able to get in contact with him there, and finally got a helpful response:

Finally! A clear answer from someone who had directly discussed the matter with him personally.

My only reservation is that Malcom Nance seems to be... an excitable individual. A look over his Substack articles and Twitter feed reveal copious exaggeration and simplistic, hyper-emotional language. So it strikes me as plausible that he misinterpreted ambivalent statements from Hitchens. (This is supported by Malcom's claim that Hitchens was "a proponent of torture", which is clearly false going by Christopher's public articles on the subject. The question is only over whether Hitchens considered waterboarding to be a form of torture, and therefore permissible or not, which Malcolm seems to have not understood.)

Still, when several individually-questionable pieces of evidence are pointing in one direction, and nothing in particular is pointing in the other, that seems like the correct conclusion. I think the story is probably true, though perhaps with a bit less conviction on Hitchens' part than he's presented as having.