Preserving the memory, and the cells, of the best cat ever

This story begins in May 2007. The Iraq War was in full swing, Windows Vista was freshly released,[1] and I was just 10 years old.

My family’s beloved black cat, Lucy, had died. Devastated, I begged my parents: we need to get another Lucy. They must have felt the same way, because a few days later, we visited the Minnesota Humane Society, where there was a crowd of cute kittens up for adoption. One stood out to me, a black kitten with green eyes. The Humane Society staff had named him Spitfire, due to his high energy. But after bringing him home, we decided to name him after an icon of rebirth: Phoenix.

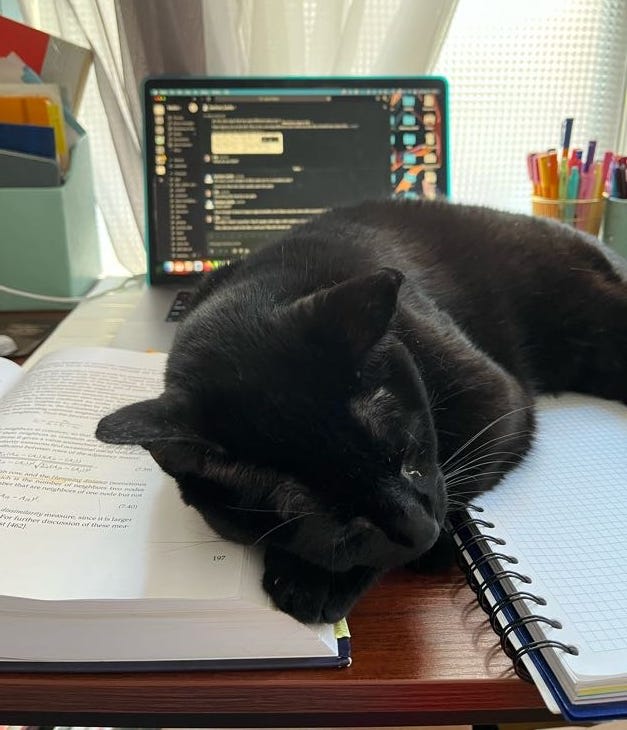

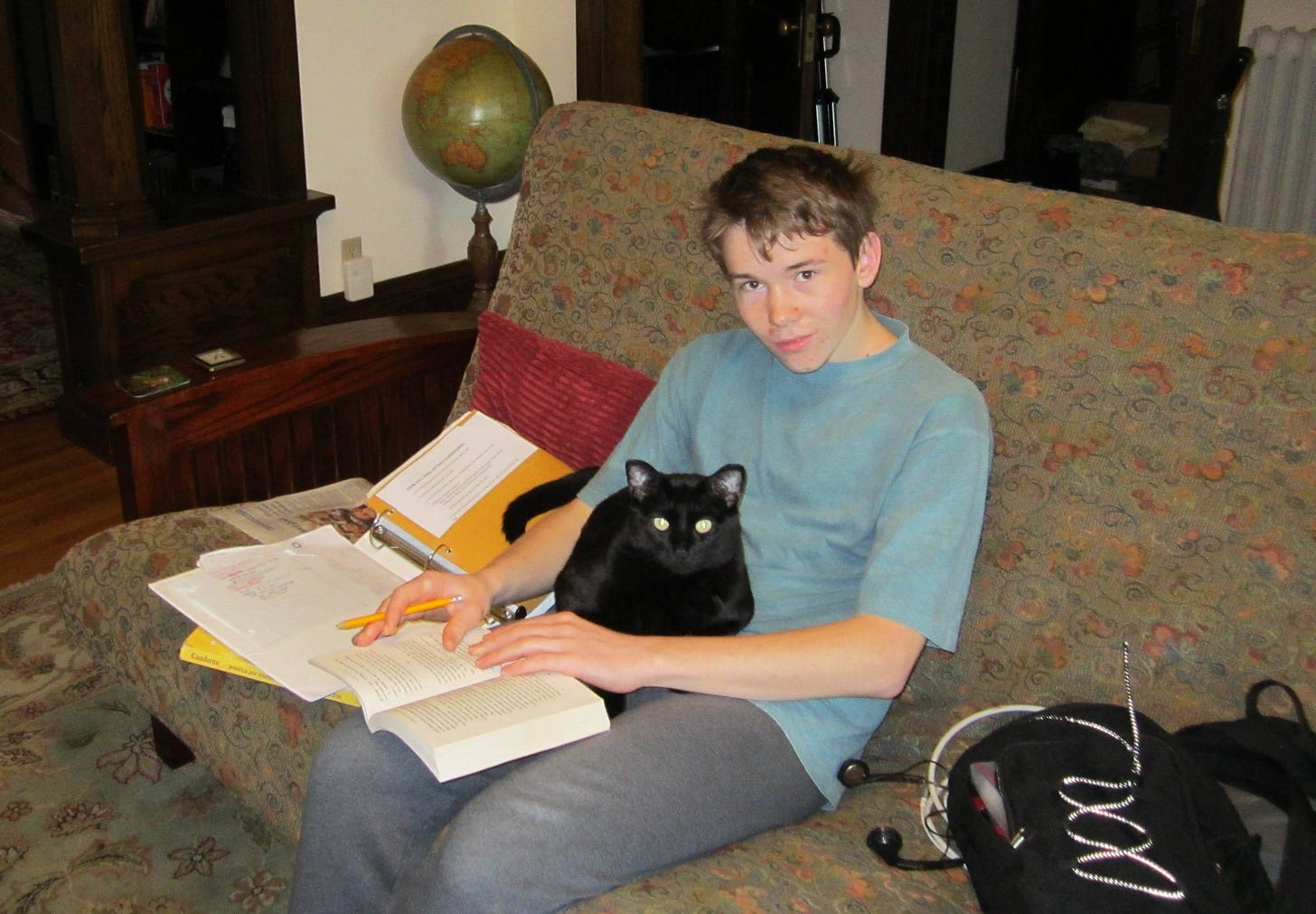

Over the years, Phoenix and I became best friends, sharing many special moments. In high school, he often helped me with my homework:

And even in college, I still saw him whenever I visited my parents. At the beginning of 2022, my partner Ula and I adopted Phoenix, welcoming him into our apartment. At this point, he was already showing his age, and, like many old cats, he had developed kidney disease. Still, he still had the zoomies from time to time, and really enjoyed his cuddles. Ula gave him a new nickname, “The Bean”, because he was “a cute little bean”

For someone who hasn’t met him, it’s hard to explain why Phoenix was the best cat ever. Of course, I’m biased. But Phoenix truly had the best of both playful energy, and calming cuddles. When he sat on your lap and purred, you felt so relaxed that you just couldn’t do anything except pet him. He also had a charming personality, including a morning routine that involved asking for fresh water in his fountain, then either sitting on the windowsill in the summer, or burrowing under the blankets in the winter. Whenever we were sick, Phoenix would always try to help us feel better. I’ve met plenty of other cats, but none of them were like Phoenix. For 17 years, he was truly a family member and a constant companion.

Unfortunately, Nature has a way of destroying everything dear to us. Domestic cats typically live for 13 - 17 years, and Phoenix was no exception. By the end of his life, he was suffering from kidney disease, arthritis, and a heart murmur. We tried to give him the best quality of life he could have. Starting in May 2024, we even injected him with subcutaneous fluids every day (100 mL lactated Ringer’s), which he tolerated remarkably well. He hated injections at the vet, but apparently trusted us enough to be injected at home. I think he understood that the fluids made him feel better.

At his last checkup in January, the vet found that his blood urea level was 5 times higher than the unhealthy threshold, and remarked that we must be taking good care of him, because he still appeared to be doing well in spite of his kidney disease. In fact, what finally did him in was not his kidneys, but a rapidly growing nasal tumor. We first noticed some swelling on Phoenix’s face around February 13, and a week later, it had progressed to the point that he was refusing food and water. We had previously discussed end-of-life plans for him, but I was surprised how quickly he declined in the end. On Friday, February 21, 2025, we had a vet come visit our apartment to put Phoenix to rest. He was just a month away from his 18th birthday.

Only mostly dead

I had often talked about preserving Phoenix’s cells after he died. After all, with a name like Phoenix, it was only fitting that one day he might be re-born as a clone. I knew that Viagen Pets had successfully cloned cats starting from skin fibroblasts. The only catch was that the cloning cost $50,000, and I really couldn’t justify spending that much when there were plenty of better causes to fund. But, if I could preserve his fibroblasts, there was a chance that I could clone him in the future when the technology was more accessible. Plus, I needed to practice fibroblast isolation anyway, because some of Ovelle’s future work will involve using skin-derived fibroblasts to generate induced pluripotent stem cell lines.

Isolating fibroblasts requires taking a skin sample, and I didn’t want to hurt Phoenix while he was still alive. After all, he had already lost the tip of one ear! So a post-mortem sample was the only option. In the last few weeks of Phoenix’s life, I read up on fibroblast culture methods, and found a helpful protocol from JoVE, a journal which publishes tutorial videos for experimental procedures. I wanted to try out the protocol using my own skin, and I got all the materials to do so, but at the end, Phoenix declined so rapidly that I didn’t get a chance to test out the method first.

Following a guide from Viagen, I took some skin samples starting about 45 minutes after death. This was more difficult than I expected. The hardest part was removing all the fur! I also was very emotional — I’ve dissected several mice over the course of my research, but it’s really different when it’s your own pet. I transported the samples to the lab in tubes of lactated Ringer’s solution, and set up the cultures. Following the JoVE protocol, I cut up the skin samples using two scalpels and put the pieces into 6-well culture plates with a small amount of growth medium.

Again, this was a bit trickier than I expected, and I had trouble cutting the pieces to be small enough before putting them into culture dishes. Following a different guide, I also cryopreserved a few skin pieces just as a backup in case the culture didn’t work.

The hardest part of the fibroblast culture was that I would have to wait for several days to know whether or not it worked. Importantly, the skin pieces needed to attach to the bottom of the culture plates, and if I was too impatient and moved the plates around too much, it might disrupt the attachment, causing the cultures to fail!

So, just to be sure, I took some additional samples the next morning (after keeping Phoenix’s body refrigerated overnight). This time, knowing what to expect, it went much more smoothly. Afterwards, we brought Phoenix’s body to the vet to be cremated, but I kept a few skin samples (in RPMI medium with antibiotics) and gave them to one of my friends who had previous experience with fibroblast culture.

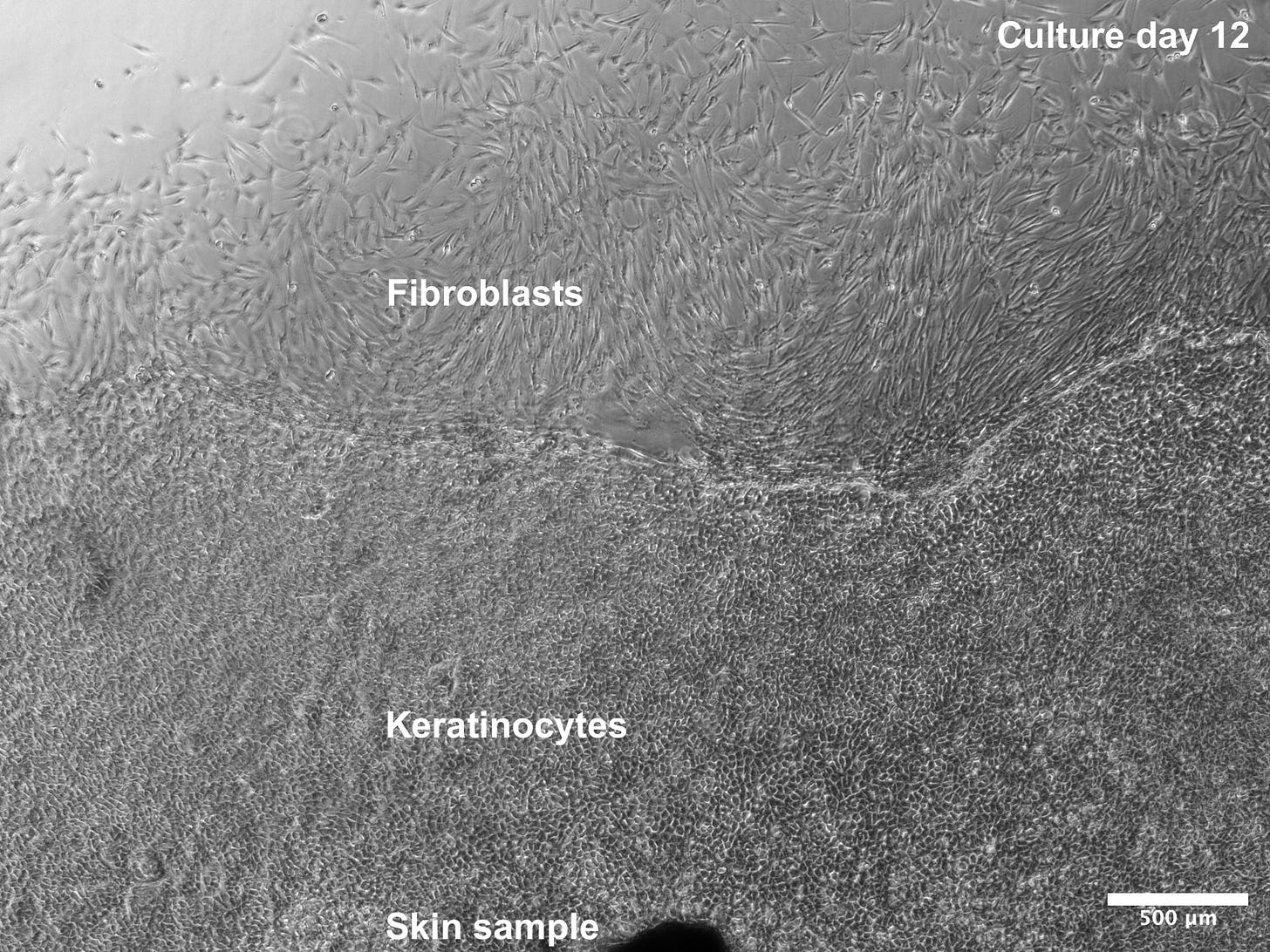

Thankfully, despite my anxiety and lack of practice, all of the cultures[2] were successful! I noticed the first signs of growth on February 25 (4 days after starting the first cultures), and soon the cells were spreading across the bottom of the culture plates. The pattern of growth basically matched the description in the tutorial video: the first cells to appear were keratinocytes,[3] but soon, fibroblasts overtook them and grew across the plates.

A new beginning?

In a few days, I will freeze the cultured fibroblasts. As Hayflick famously discovered, fibroblasts can’t be cultured indefinitely, and furthermore, mutations or epigenetic abnormalities could accumulate in cell culture. Thankfully, I have plenty of liquid nitrogen storage available, so a few extra vials of cells won’t get in the way of my research. And after this experience, I’m definitely more confident in my ability to culture fibroblasts from skin, which will come in handy for generating new iPSC lines.

In the meantime, I want to design a really nice urn for Phoenix’s ashes. I have an idea for something like a phoenix egg, with a winged cat sitting on top.

And who knows, maybe 25 years from now, we’ll have a Phoenix Junior. The second time around, I want to do some gene editing to make his kidneys stronger. And maybe also make his eyes express luciferase . . .

- ^

The world would have to wait a little longer to get the iPhone, which was announced in January 2007 but released in June.

- ^

Including the ones from Feb. 21, Feb. 22, and even the ones from Feb. 24 which my friend set up. Clearly, Phoenix wasn’t all dead. He was only mostly dead.

- ^

Keratinocytes are not great cells for somatic cell nuclear transfer cloning; it seems that fibroblasts work better for this.

Touching. Thank you for this.

When I was 11 I cut off some of my very-much-alive cat's fur to ensure future cloning would be possible, and put it in a little plastic bag I hid from my parents. He died when I was 15, and the bag is still somewhere in my Trunk of Everything.

I don't imagine there's much genetic content left but also I have a vague intuition that we severely underestimate how much information a superintelligence could extract from reality—so I'll keep onto a lingering hope.

My past self would have wanted me to keep tabs on how the technology is going.

(For those hypothetically wondering, I also cut off some of my own hair that day in case someone would like to clone ME after death, and that bag is still in the Trunk as well.)

(And I couldn't do this to my cat, but my past self also wrote over a million words about everything he experienced in a google docs in the hopes that the clone could know who his predecessor was and model himself accordingly. I was one of those terrified-of-death kids.)

I'm sorry to break this to you, but cloning requires live cells, not just DNA. This is one of the reasons why it's so hard to bring back the woolly mammoth. (The other reason is that it's really hard to do IVF on elephants.)

So if you want to make a clone, you'll need to do something like what I did (take cells and preserve them in liquid nitrogen).