LLMs appear to universally learn a feature in their embeddings representing the frequency / rarity of the tokens they were trained on

...I use Olah et al.'s definition of a feature as a direction in the vector space of a model's weights / activations in a given layer.

If you define 'feature' this way, and you look only at post-training models, including your nanoGPT models, is it necessarily learned? Or are they something else, like left near their initialization and then it's every other feature which is learned and so the 'rareness' feature is not really a feature, so much as it is 'the absence of every other feature', maybe?

It seems like, almost by definition from gradient descent, if tokens are rarely or never present in the training (as seems to be the case with a lot of the glitch tokens like SolidGoldMagikarp, especially the spam ones, like all the Chinese porn ones that somehow got included in the new GPT-4o tokenization), it is difficult for a model to learn anything about rare tokens - they simply never contribute to the output because they are never present, and there are no gradients. And then activation steering or other things using the 'rareness feature' would be weak or not do anything particularly consistent or interesting, because what is left is going to be effectively meaningless jitter from tiny numerical residues.

Very true. If a token truly never appears in the training data, it wouldn't be trained / learned at all. Or similarly, if it's only seen like once or twice it ends up "undertrained" and the token frequency feature doesn't perform as well on it. The two least frequent tokens in the nanoGPT model are an excellent example of this. They appear like only once or twice and as a result don't get properly learned, and as a result end up being big outliers.

@Bogdan Ionut Cirstea I think it is plausible explanation for feature alignment between brain and LLMs?

Summary

Definitions / Notation

I use Olah et al.'s definition of a feature as a direction in the vector space of a model's weights / activations in a given layer.

Tied weights are a common LLM architectural choice where in order to reduce the number of parameters in the model and align the embeddings and unembeddings, the same weights matrix is used for both. Of the models discussed here the GPT 2 series, Gemma series, and Phi 3 Small models use tied weights. All others have separate weight matrices for their embeddings and unembeddings. For brevity, in models with tied weights, I will refer to both the embeddings and unembeddings as simply the model's "embeddings" since the two are identical.

Linear probing is just a fancy name for using linear regression (or classification) on the internal representations (weights or activations) of models.

How to Find the Feature

PC_matrix. It will also be of size V×DPC_matrixseparately, regressing the principal component values vs. log10(token_count+1) for each token. While performing each regression, evaluate the p-value of that principal component and keep a list of all principal components with a p-value ≤0.05DCode for this process can be found here, and the final feature vectors for all the models I studied can be found here.

Results

I was able to find the feature in 20 different models: 18 popular open source LLMs and their variants plus two smaller, GPT-style models trained on a fully known training dataset for validation. This includes a variety of different model sizes (from 10M to 70B parameters), both base models and instruction tuned models, and even code models. The results are summarized in the table below:

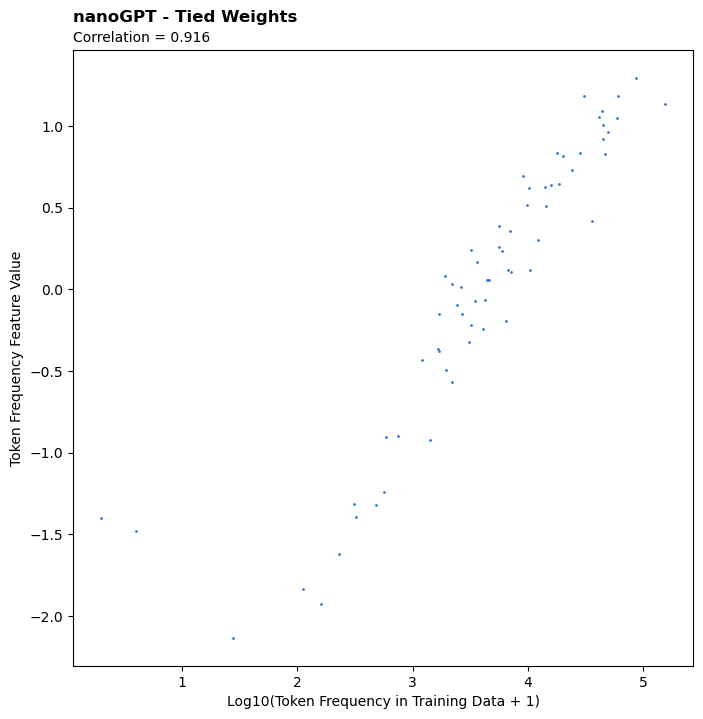

You'll notice the feature correlates very strongly with the log token frequency (typically ~0.9). To visualize this, here's a scatter plot for one specific model (GPT 2 - Small). (Scatter plots for all other models, plus code to replicate the results can be found here.)

Interestingly, we see high correlations for both model embeddings and unembeddings. In some cases, we even observe that the embedding correlation is stronger than the unembedding correlation, despite initially expecting the feature to be stronger in unembeddings.

The weakest correlations were observed for the CodeGemma models. My hypothesis for this is that, being code models, the data they were trained on differs more substantially from our proxy dataset (OpenWebText) than it did for the other, more standard text models. I believe this is also the case for the regular Gemma models to a lesser extent, due to more of their training data being non-English text. (OpenWebText filters out non-English webpages.)

All that said, the only way to truly confirm the feature measures training data token frequency is to use a model's actual training data instead of a proxy. As such, I trained two small character-level language models on the works of Shakespeare using Andrej Karpathy's nanoGPT repo. I trained one version with tied weights (in true GPT fashion) and one without. This experiment yielded the single highest correlation observed across the models investigated, generally confirming that yes, the feature actually measures training data token frequency.

Possible Uses

I also explored a couple possible uses for this feature, beyond improving model understanding alone.

Identifying Glitch Tokens

One use for this feature is as a way to identify candidate "glitch tokens" a la the infamous SolidGoldMagikarp token. Indeed, one leading hypothesis for the existence of these tokens is that they're tokens that appear in a model's tokenizer but never (or only very rarely) appear in the model's actual training data. As such, this is an extremely natural use for this feature.

While I haven't conducted a thorough review, initial inspection suggests the tokens scored as least frequent by the feature align well with the list of anomalous tokens shared in SolidGoldMagikarp II: technical details and more recent findings.

Activation Steering

I also performed some initial exploration on how this feature could potentially be used to influence model behavior through activation steering. I did this by simply adding the feature vector times some chosen constant c to the final hidden state of the model before the unembedding matrix is applied. Note, due to computational / time constraints, this investigation was conducted on GPT 2 - Small only, and so the findings may or may not generalize to the other models.

One important observation from this exercise was that it required very large / small steering vectors (i.e. very large / small values of c) to change model outputs. Indeed, at its most extreme it typically required |c|>1000 to push models outputs to the extremes of the feature: always outputting the most or least frequent token according to the feature. With other, unrelated features this can typically be done with much lower values c, e.g. |c|>100 or even less. This suggests the model pays relatively little attention to this feature. Ultimately, because of this, I don't believe it's a strong target for activation steering efforts.

Nevertheless, the activation steering did have the effect you might anticipate of pushing the model to use more common / rare tokens. This is demonstrated in the activation steering example pictured below. In this example, the default first token output is

" Paris", but by pushing the feature in an increasingly negative direction (i.e. more negative values of 𝑐) we're eventually able to force it to output the rarer" Cologne"token. Conversely, we can also push it in the other more positive direction to force it to output first the" London"and then the" New"token instead, both of which are more common tokens.Final Thoughts / Next Steps

Obviously, this is not a surprising feature. It definitely seems like a feature models should learn. As such, I hope that this work:

Given this, a natural next project, building off this one, would be to try to demonstrate the universality of a "feature" for token bigram statistics. The theory from A Mathematical Framework for Transformer Circuits suggests this should be related to the product of embedding and unembedding matrices, but to my knowledge this hasn't yet been empirically demonstrated as universal in LLMs.

In fact, if the bigram statistic theory is correct and universal, that could explain why GPT 2 - Small was relatively insensitive to my attempts to steer it using the token frequency feature. Specifically, my current hypothesis is that the feature exists and is important to the model not for providing some sort of baseline prior on the output tokens, but rather as a feature the model uses to learn / store bigram statistics (which ultimately become a better prior it can use / update).

Acknowledgements

I want to express my gratitude to all the companies who made their models open source (OpenAI, Meta, Mistral, Google, and Microsoft). This work would have been impossible otherwise as I definitely don't have the means to train any of these models myself! I also want to thank Hugging Face for hosting the models and providing helpful code for pulling / interacting with them, and of course Andrej Karpathy for building and sharing his nanoGPT repo.