I have a few shorter more focused posts in the works, including my practical short version of On Bounded Distrust. In the meantime, it makes sense to continue to clean out the backlog of roundup style things.

Let Your Children Play

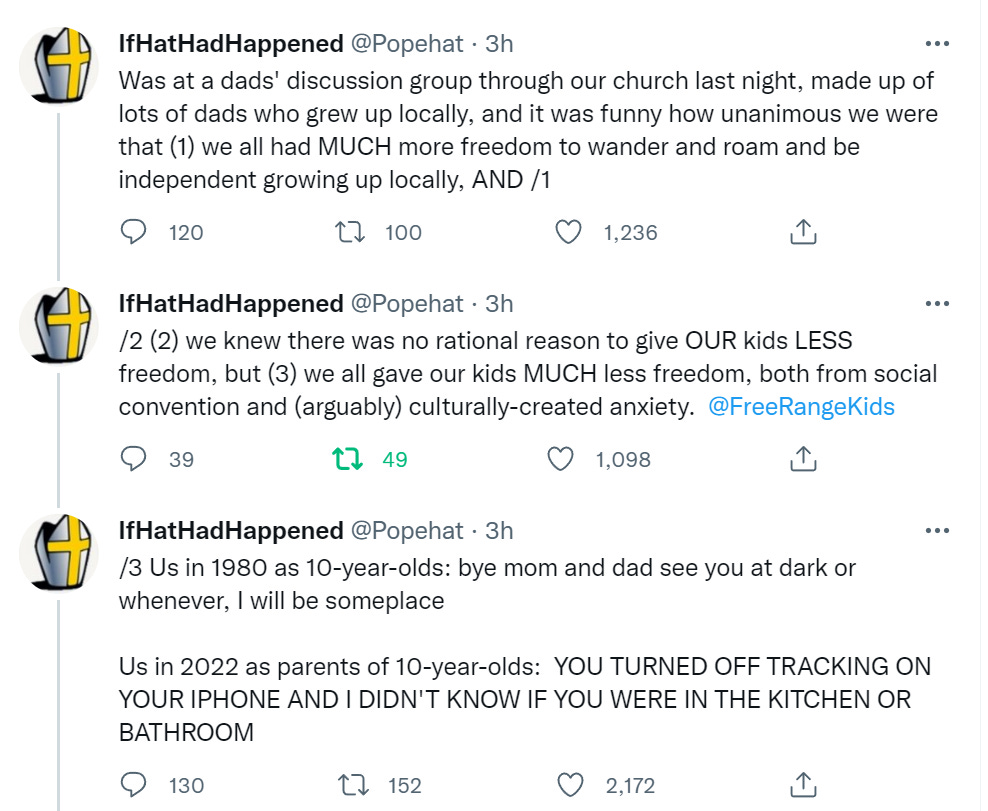

Sane 2022 parents of 10-year-olds: I would like to let you go outside without me. I am terrified that someone will call the cops and they will take you away from me.

That is a thing now. As in parents being thrown in jail for letting their eight year old child walk home from school on their own.

As they stood on her porch, the officers told Wallace that her son could have been kidnapped and sex trafficked. “‘You don’t see much sex trafficking where you are, but where I patrol in downtown Waco, we do,'” said one of the cops, according to Wallace.

Did things get more dangerous since 1980, when we were mostly sane about this? No. They got vastly less dangerous, in all ways other than the risk of someone calling the cops.

The numbers on ‘sex trafficking’ and kidnapping by strangers are damn near zero.

The incident caused ‘ruin your life’ levels of damage.

Child services had the family agree to a safety plan, which meant Wallace and her husband could not be alone with their kids for even a second. Their mothers—the children’s grandmothers—had to visit and trade off overnight stays in order to guarantee the parents were constantly supervised. After two weeks, child services closed Wallace’s case, finding the complaint was unfounded.

…

Wallace’s sister has started a GoFundMe for her. She is in debt after losing her job and paying for the lawyer and the diversion program. She also hopes to hire a lawyer to get her record expunged so that she can work with kids again.

One of my closest friends here in New York is strongly considering moving to the middle of nowhere so that his child will be able to walk around outside, because it is not legally safe to do that anywhere there are people.

Claim that UNICEF thinks Dutch children are the happiest in the world and that this is because they bike everywhere, things are designed to make this work, and they therefore have freedom to move around.

Childless World

This is also related to the thing where a lot of places give off the vibe that life does not involve children, and children are a weird, shameful and irresponsible lifestyle choice.

I sense this type of attitude ebb and flow in power as I move between places.

School Daze

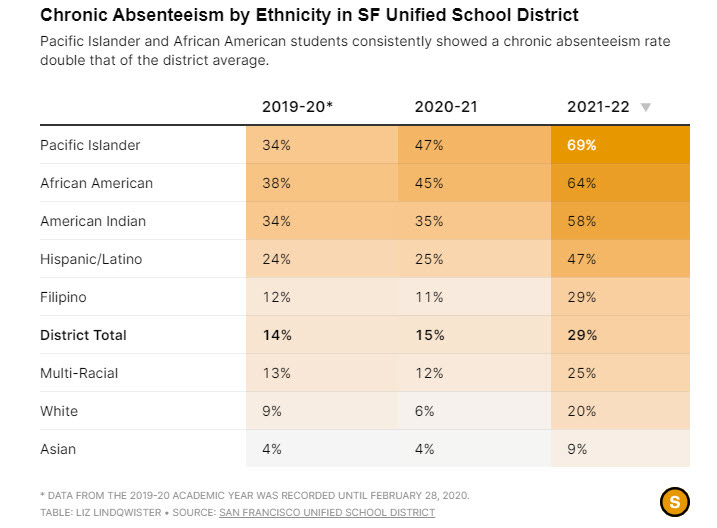

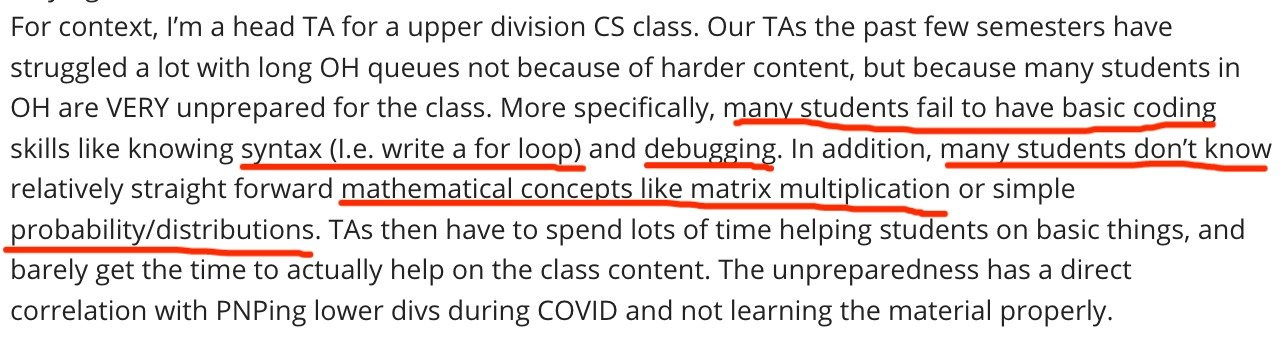

It’s not like the kids were attending school that much anyway (MR). The chart is San Francisco, but it is far from unique in this. This headline says ‘41% of NYC students were chronically absent’ last year, versus a historical expectation of ~25%.

Note that in school parlance, ‘chronic absentee’ means you missed 18 days of school out of 180. Thus, someone who reports as demanded 90% of the time is still ‘chronically absent,’ no matter the cause.

Public school enrollment continues to be 3% below pre-pandemic levels. Many responded with ‘at least some good has come of this.’

The degree of learning in schools, even high end ones, leaves something to be desired.

I simply don’t know how to update far enough in the appropriate directions.

A paper compared students answers on homework questions to their later answers to the same question posed on an exam. They found that in the past this correlation was high, and said this meant that the homework helped students. One obvious alternative explanation is that knowing X is correlated with knowing X.

None of this is ‘benefit.’ Then, the study notes that this correlation has gone down, due to a large group of students who don’t show this pattern – they get the homework right by copying it, then get the exam question wrong anyway.

Via MR, paper from India says that 18 months of school closure cost students 0.7 sigma declines in math and 0.34 in language by December 2021, but two thirds of it was made up within six months, with a claim that an after school program aided this recovery. If it is this easy to catch back up, a lot of time must be getting wasted.

Null hypothesis watch via MR, as paper claims short unit on self-regulation in first grade has substantial positive effects on children’s entire academic careers.

Math Trainer program for faster mental arithmetic. You know, for kids.

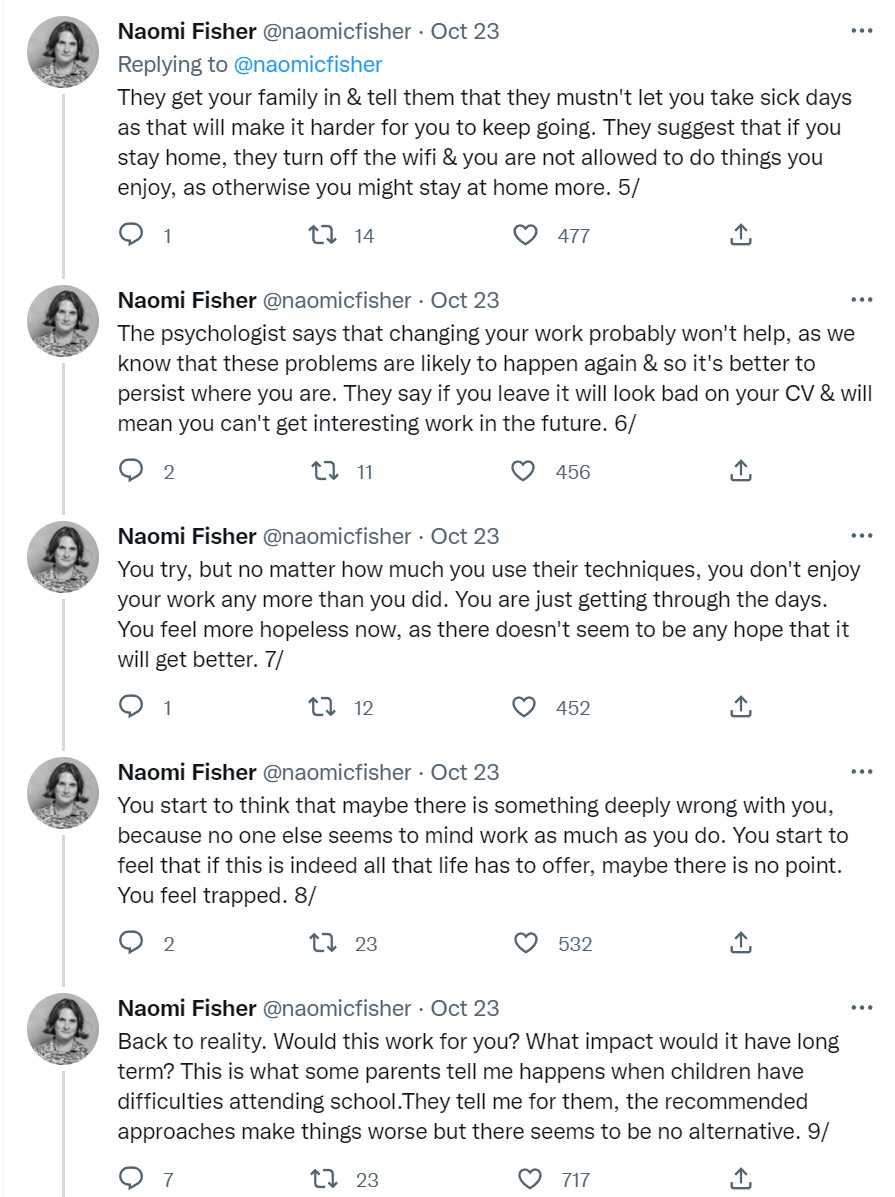

This was originally in the context of kids in particular trouble. It works even better as a simple description of school in general. This is not an outlier-only problem. What do you do when kids don’t want to go to school? What percentage of kids do you think want to go to school, or would if they felt they had any choice in the matter? If they thought ‘not going’ wouldn’t lead to escalating retaliations?

Can anyone wonder why in-person schooling raises youth suicide rates (paper)?

Along with everything else it does, school dramatically raises the economic cost of raising kids even if tuition is zero. Those who can have their children help run farms or other businesses have a large advantage over those that do not while also having larger families. Does doing this cripple their children’s future? It does if society explicitly retaliates sufficiently hardcore against those not sacrificing a decade to properly signal. If it is more a question of who learns more and more useful things, the answer is far less clear. As long as some attention is given directly to core academic subjects I would be inclined to take someone who had real world experience trying to accomplish things or especially starting and doing business, over those who spent that time in classrooms.

Fight Fiercely Harvard

Rob Henderson speculates it might be good that we don’t expand Harvard and other schools, because those with those degrees feel entitled to elite status. Disgruntled people who didn’t get the status they feel entitled to cause instability. An alternative hypothesis is that the elite status they want is going to Harvard and their kids going to Harvard, which you can totally fix by letting more people go to Harvard.

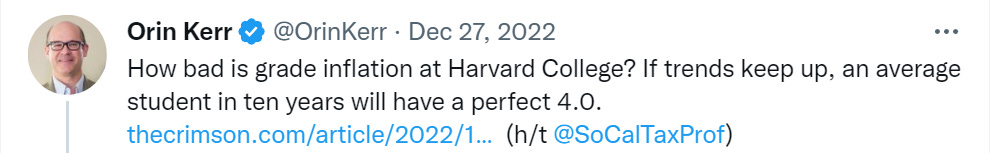

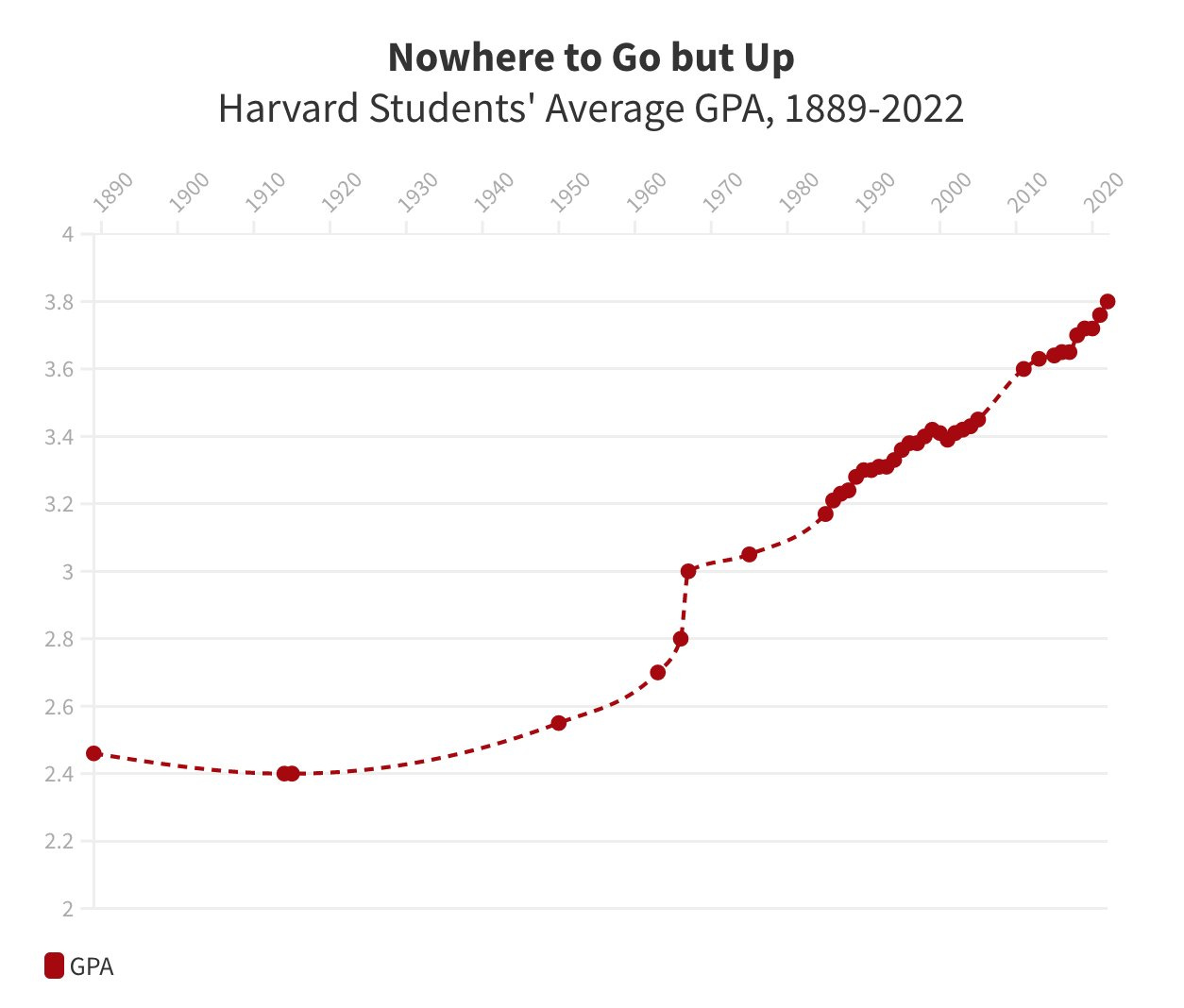

Tyler Cowen calls his post the battle for academic standards. I would have called it the battle against academic standards.

Several responses along the lines of ‘Harvard is getting more selective’ and Orin responds with variations on ‘a possibility worth examining.’ No. Effect size is too big.

Half of all sub-4.0 space eliminated in ten years because the students are that much smarter and more interested in maximizing grades? There’s that many more great students out there? Really?

The decline in acceptance rate is also, upon quick examination, mostly a mirage. It is driven by a rise in applications. I do not think Harvard is much more selective in 2022 than it was in 2012. What is happening is the practical cost of applying to Harvard is declining. Also students are realizing that even if they have a 1% chance of getting in, what is it worth to get into Harvard?

When I was applying to colleges, my high school refused to cooperate with more than seven applications. Thus I didn’t apply to Harvard or MIT, despite them being obviously my #1 and #2 picks in some order if I were to get in, because they seemed too unlikely even as reaches, and am still bitter Stanford tricked my parents into eating a slot. If I’d had a common application and free run of the place? I’d have applied for a minimum of 20-30 places, maybe 50+, on the theory that someone might randomly value qualifying for the USAMO on a particular day more than anyone else, and the value of a better college or a strangely generous scholarship is super high – toss them all in the air for a few thousand dollars, and then see what my real choices were. I doubt it changes where I end up going given how things worked out, but you never know, maybe MIT, Harvard or Yale says yes. It sure drives down acceptance rates at the top.

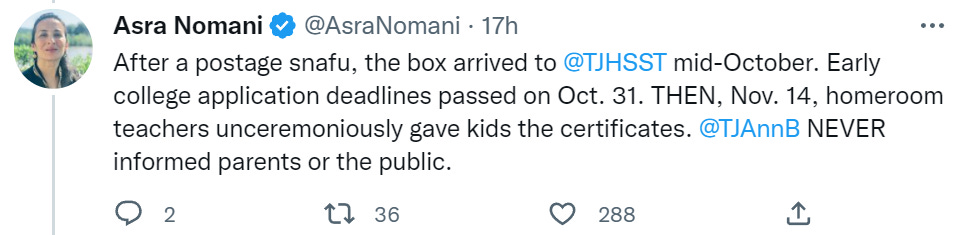

My old high school’s traditional rival, Thomas Jefferson, withheld news of National Merit awards from families, which many say is sabotaging their college admissions. If you want equal outcomes, you have two options, and one is a hell of a lot easier than the other.

I push back against the idea that this advances no interests. College admissions are ideally a matching problem. In practice, on the margins of merit scholars, college admissions are a zero sum signaling game. This is not going to change the number of kids admitted to various schools, or the amount of scholarship money available. If you want to advance the interests of your group at the expense of another group, on whatever basis, then this seems like a relatively harmless way to do that. And yes, this would advance the interests of politically preferred groups, because it disproportionally hurts other students from other groups in the zero sum game.

They still gave the awards to students, but too late to include them on early admissions applications. That’s quite the albatross on its own. It is where the extra push is most valuable.

I do see advantage in not telling parents or other students. This lets recipients decide whether to inform others.

Why would a student not inform others about such an award? Presumably because the parents would then do things the kid wants to avoid, like endlessly bragging about it to everyone, or forcing the kid to apply to schools they don’t want or competitions they hate, or things like that. I speak from personal experience here.

Similarly, if a student wants to tell other students about the award, they can do that. If they want to avoid this for whatever social reasons – and I can think of quite a few good ones – they can avoid it. Making a big deal out of it is not obviously doing the kid any favors.

And yes, sometimes that choice to hide this info will be because the kid is less ambitious, or less prioritizing of academics, and thus will end up at a ‘worse’ school. That is their choice. I do not see this as obviously hostile.

Tyler Cowen says universities are in crisis and declining in status. He notes the new emphasis on computer science, where they are outcompeted by the private sector for status because status there is based on capability and accomplishment and real world tests.

He notes there is youth mental health crisis, which he says is not the fault of colleges. Why is he so sure? We have structured young lives around taking on debt to go to college, and putting immense pressure on to follow the rules of the dance so you can get in. Ideological movements that are rooted in college campuses and that instill their ideas into children are, shall we say, not helping their mental health outlooks. If we got rid of college as a default life path, I bet that solves a good portion of our youth mental health crisis.

He does not link up declining academia with grade inflation or declining academic standards. Seems like an important piece of the puzzle.

He says students have more absences, excuses and missed assignments lately, and says this makes it harder to run an effective university. My guess is this is more a symptom of decline than a cause. Students have realized the returns to anything but the sheepskin effect are not so high, and required efforts to pass are lower than ever.

This goes hand in hand with his observation that the smartest people no longer want to be in academia. Its requirements seem onerous, jobs are difficult to get, and for what? I would at this point classify trying to be a professor as similar to writer or rock star, something you only do if you can’t not do it.

What Is Good In Life?

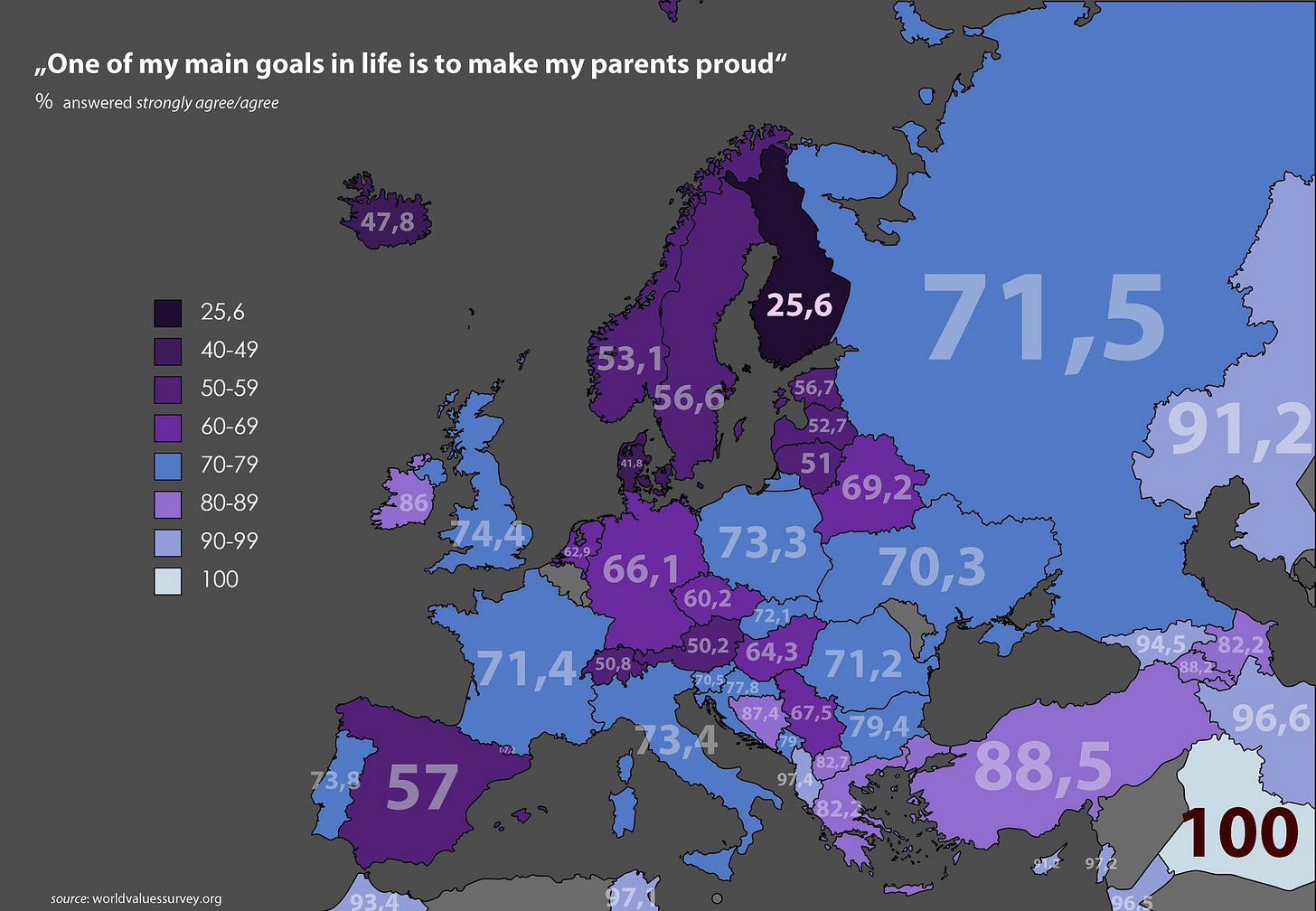

I simultaneously would have answered ‘no,’ would expect most people in my social circles to answer no, think it is clear that this being a near-universal is a very bad sign, and also that 25.6% is terrifying. It’s something like ‘there is a right amount of the thing this is a proxy for, and that very much is not it.’

Child Tax Credit Blues

(I plan to talk more about this on its own in the future.)

A good idea is to Give Parents Money to help them raise their children and to reduce the net financial burden on those who decide to have (more) kids. It reduces child poverty, it is equitable, it makes people’s lives better, it increases birth rates that need to increase, it enables more people to have the things that matter in life.

The problem is that, despite initial hopes that such an obviously good idea would also be highly popular, this has not proven to be the case. A lot of that is due to people really disliking it when either such payments are framed as ‘welfare’ or when they go to ‘people who don’t need them.’

So both the too poor and the too rich need to be screened out, despite such payments to both such groups making good sense. Very poor children need our help. Those that are ‘rich’ face effectively very high costs to raising children, due to the cost of schools, nannies and space in the expensive places they live, and the high hourly opportunity cost of their own time. It certainly makes sense to give them relative help, shifting funds from the childless rich to the rich with children, which is what the credit would do (since it is then paid for via progressive taxation that can be adjusted to be more progressive, if desired).

The other problem is that means testing is a logistical nightmare in the best of times, and mostly we suck at implementation. For example, see the latest proposal in New York. It pays out quarterly, so everyone’s income needs to be estimated in advance to decide who gets those payments in what quantity, and then everyone has to jump through hoops to explain when expectations should change and that they made ‘good faith’ efforts to keep estimates accurate and so on.

Whereas the obviously correct solution, as Matt Yglesias points out, is to pay everyone the maximum, at least on the ‘too rich’ end, and then collect it back in the form of an additional tax. Which would then in turn point out that the system adds up to an absurdity, which I would consider a feature but I would expect the legislature to consider it a bug. Perhaps this could dodge being misrepresented if the rich person algorithm was entirely handled on one’s tax return.

The graph of average GPA at Harvard vs. time is interesting. I thought back to being a 3rd-year Arts student in '78/79 at a public university in western Canada.

A very good prof told us that in the Department of Psychology (or perhaps the Faculty of Arts in general), the median mark was set as the demarcation between a C+ and a B (and thus, the median GPA would have been 2.75).

Per the graph, the average Harvard GPA at the time was c. 3.1. (The slope is steep at that point, so there's some +/- possible, and the median may have been different.)

Both average/median GPAs are higher than the formal grade definitions of my childhood. As I recall, they were:

A - Excellent 80 - 100% 4.0

B - Good 70 - 79% 3.0

C - Average 60 - 69% 2.0

D - Poor 50 - 59% 1.0

F - Fail 0 - 49% 0.0

All of this to say, by definition the average GPA should have been a C/65%.

It appears grade inflation has been a real thing for a long time.