Our current big stupid: not preparing for 40% agreement

Epistemic status: lukewarm take from the gut (not brain) that feels rightish

The "Big Stupid" of the AI doomers 2013-2023 was AI nerds' solution to the problem "How do we stop people from building dangerous AIs?" was "research how to build AIs". Methods normal people would consider to stop people from building dangerous AIs, like asking governments to make it illegal to build dangerous AIs, were considered gauche. When the public turned out to be somewhat receptive to the idea of regulating AIs, doomers were unprepared.

Take: The "Big Stupid" of right now is still the same thing. (We've not corrected enough). Between now and transformative AGI we are likely to encounter a moment where 40% of people realize AIs really could take over (say if every month another 1% of the population loses their job). If 40% of the world were as scared of AI loss-of-control as you, what could the world do? I think a lot! Do we have a plan for then?

Almost every LessWrong post on AIs are about analyzing AIs. Almost none are about how, given widespread public support, people/governments could stop bad AIs from being built.

[Example: if 40% of people were as worried about AI as I was, the US would treat GPU manufacture like uranium enrichment. And fortunately GPU manufacture is hundreds of time harder than uranium enrichment! We should be nerding out researching integrated circuit supply chains, choke points, foundry logistics in jurisdictions the US can't unilaterally sanction, that sort of thing.]

TLDR, stopping deadly AIs from being built needs less research on AIs and more research on how to stop AIs from being built.

*My research included 😬

As recently as early 2023 Eliezer was very pessimistic about AI policy efforts amounting to anything, to the point that he thought anyone trying to do AI policy was hopelessly naive and should first try to ban biological gain-of-function research just to understand how hard policy is. Given how influential Eliezer is, he loses a lot of points here (and I guess Hendrycks wins?)

Then Eliezer updated and started e.g. giving podcast interviews. Policy orgs spun up and there are dozens of safety-concerned people working in AI policy. But this is not reflected in the LW frontpage. Is this inertia, or do we like thinking about computer science more than policy, or is it something else?

It depends on overall probability distibution. Previously Eliezer thought something like that p(doom|trying to solve alignment) = 50% and p(doom|trying to solve AI ban without alignment) = 99% an then updated to p(doom|trying to solve alignment) = 99% and p(doom|trying to solve AI ban without alignment) = 95%, which makes solving AI ban even if pretty much doomed but worthwhile. But if you are, say, Alex Turner, you could start with the same probabilities, but update towards p(doom|trying to solve alignment) = 10%, which makes publishing papers on steering vectors very reasonable.

The other reasons:

- I expect majority of policy people to be on EA forum, maybe I am wrong;

- Kat Woods has large twitter thread about how posting on Twitter is much more useful than posting on LW/AF/EAF in terms of public outreach.

Seems reasonable except that Eliezer's p(doom | trying to solve alignment) in early 2023 was much higher than 50%, probably more like 98%. AGI Ruin was published in June 2022 and drafts existed since early 2022. MIRI leadership had been pretty pessimistic ever since AlphaGo in 2016 and especially since their research agenda collapsed in 2019.

I am talking about belief state in ~2015, because everyone was already skeptical about policy approach at that time.

Strong agree and strong upvote.

There are some efforts in the governance space and in the space of public awareness, but there should and can be much, much more.

My read of these survey results is:

AI Alignment researchers are optimistic people by nature. Despite this, most of them don't think we're on track to solve alignment in time, and they are split on whether we will even make significant progress. Most of them also support pausing AI development to give alignment research time to catch up.

As for what to actually do about it: There are a lot of options, but I want to highlight PauseAI. (Disclosure: I volunteer with them. My involvement brings me no monetary benefit, and no net social benefit.) Their Discord server is highly active and engaged and is peopled with alignment researchers, community- and mass-movement organizers, experienced protesters, artists, developers, and a swath of regular people from around the world. They play the inside and outside game, both doing public outreach and also lobbying policymakers.

On that note, I also want to put a spotlight on the simple action of sending emails to policymakers. Doing so and following through is extremely OP (i.e. has much more utility than you might expect), and can result in face-to-face meetings to discuss the nature of AI x-risk and what they can personally do about. Genuinely, my model of a world in 2040 that contains humans is almost always one in which a lot more people sent emails to politicians.

Epistemic status: I have written only a few emails/letters myself and haven't personally gotten a reply yet. I asked the volunteers who are more prolific and successful in their contact with policymakers, and got this response about the process (paraphrased).

It comes down to getting a reply, and responding to their replies until you get a meeting / 1-on-1. The goal is to have a low-level relationship:

- Keep in touch, e.g. through some messaging service that feels more personal (if possible)

- Keep sending them information

- Suggest specific actions and keep in touch about them (motions, debates, votes, etc.)

There are some conversations about policy & government response taking place. I think there are a few main reasons you don't see them on LessWrong:

- There really aren't that many serious conversations about AI policy, particularly in future worlds where there is greater concern and political will. Much of the AI governance community focuses on things that are within the current Overton Window.

- Some conversations take place among people who work for governments & aren't allowed to (or are discouraged from) sharing a lot of their thinking online.

- [Edited] The vast majority of high-quality content on LessWrong is about technical stuff, and it's pretty rare to see high-quality policy discussions these days (Zvi's coverage of various bills would be a notable exception). Partially as a result of this, some "serious policy people" don't really think LW users will have much to add.

- There's a perception that LessWrong has a bit of a libertarian-leaning bias. Some people think LWers are generally kind of anti-government, pro-tech people who are more interested in metastrategies along the lines of "how can me and my smart technical friends save the world" as opposed to "how can governments intervene to prevent the premature development of dangerous technology."

If anyone here is interested in thinking about "40% agreement" scenarios or more broadly interested in how governments should react in worlds where there is greater evidence of risk, feel free to DM me. Some of my current work focuses on the idea of "emergency preparedness"– how we can improve the government's ability to detect & respond to AI-related emergencies.

LessWrong does not have a history of being a particularly thoughtful place for people to have policy discussions,

This seems wrong. Scott Alexander and Robin Hanson are two of the most thoughtful thinkers on policy in the world and have a long history of engaging with LessWrong and writing on here. Zvi is IMO also one of the top AI policy analysts right now.

Definitely true policy thinking here has a huge libertarian bent, but I think it's pretty straightforwardly wrong to claim that LW does not have a history of being a thoughtful place to have policy discussions (indeed, I am hard-pressed to find any place in public with a better history)

I think you're too close to see objectively. I haven't observed any room for policy discussions in this forum that stray from what is acceptable to the mods and active participants. If a discussion doesn't allow for opposing viewpoints, it's of little value. In my experience, and from what I've heard from others who've tried posting here and quit, you have not succeeded in making this a forum where people with opposing viewpoints feel welcome.

You are not wrong to complain. That's feedback. But this feels too vague to be actionable.

First, we may agree on more than you think. Yes, groupthink can be a problem, and gets worse over time, if not actively countered. True scientists are heretics.

But if the science symposium allows the janitor to interrupt the speakers and take all day pontificating about his crackpot perpetual motion machine, it's also of little value. It gets worse if we then allow the conspiracy theorists to feed off of each other. Experts need a protected space to converse, or we're stuck at the lowest common denominator (incoherent yelling, eventually). We unapologetically do not want trolls to feel welcome here.

Can you accept that the other extreme is bad? I'm not trying to motte-and-bailey you, but moderation is hard. The virtue lies between the extremes, but not always exactly in the center.

What I want from LessWrong is high epistemic standards. That's compatible with opposing viewpoints, but only when they try to meet our standards, not when they're making obvious mistakes in reasoning. Some of our highest-karma posts have been opposing views!

Do you have concrete examples? In each of those cases, are you confident it's because of the opposing view, or could it be their low standards?

Your example of the janitor interrupting the scientist is a good demonstration of my point. I've organized over a hundred cybersecurity events featuring over a thousand speakers and I've never had a single janitor interrupt a talk. On the other hand, I've had numerous "experts" attempt to pass off fiction as fact, draw assumptions from faulty data, and generally behave far worse than any janitor might due to their inflated egos.

Based on my conversations with computer science and philosophy professors who aren't EA-affiliated, and several who are, their posts are frequently down-voted simply because they represent opposite viewpoints.

Do the moderators of this forum do regular assessments to see how they can make improvements in the online culture so that there's more diversity in perspective?

can't comment on moderators, since I'm not one, but I'd be curious to see links you think were received worse than is justified and see if I can learn from them

I'm echoing other commenters somewhat, but - personally - I do not see people being down-voted simply for having different viewpoints. I'm very sympathetic to people trying to genuinely argue against "prevailing" attitudes or simply trying to foster a better general understanding. (E.g. I appreciate Matthew Barnett's presence, even though I very much disagree with his conclusions and find him overconfident). Now, of course, the fact that I don't notice the kind of posts you say are being down-voted may be because they are sufficiently filtered out, which indeed would be undesirable from my perspective and good to know.

Oh good point– I think my original phrasing was too broad. I didn't mean to suggest that there were no high-quality policy discussions on LW, moreso meant to claim that the proportion/frequency of policy content is relatively limited. I've edited to reflect a more precise claim:

The vast majority of high-quality content on LessWrong is about technical stuff, and it's pretty rare to see high-quality policy discussions on LW these days (Zvi's coverage of various bills would be a notable exception). Partially as a result of this, some "serious policy people" don't really think LW users will have much to add.

(I haven't seen much from Scott or Robin about AI policy topics recently– agree that Zvi's posts have been helpful.)

(I also don't know of many public places that have good AI policy discussions. I do think the difference in quality between "public discussions" and "private discussions" is quite high in policy. I'm not quite sure what the difference looks like for people who are deep into technical research, but it seems likely to me that policy culture is more private/secretive than technical culture.)

It's not that people won't talk about spherical policies in a vacuum, it's that the actual next step of "how does this translate into actual politics" is forbidding. Which is kind of understandable, given that we're probably not very peopley persons, so to speak, inclined to high decoupling, and politics can objectively get very stupid.

In fact my worst worry about this idea isn't that there wouldn't be consensus, it's how it would end up polarising once it's mainstream enough. Remember how COVID started as a broad "Let's keep each other safe" reaction and then immediately collapsed into idiocy as soon as worrying about pesky viruses became coded as something for liberal pansies? I expect with AI something similar might happen, not sure in what direction either (there's a certain anti-AI sentiment building up on the far left but ironically it denies entirely the existence of X-risks as a right wing delusion concocted to hype up AI more). Depending on how those chips fall, actual political action might require all sorts of compromises with annoying bedfellows.

the problem "How do we stop people from building dangerous AIs?" was "research how to build AIs".

Not quite. It was to research how to build friendly AIs. We haven't succeeded yet. What research progress we have made points to the problem being harder than initially thought, and capabilities turned out to be easier than most of us expected as well.

Methods normal people would consider to stop people from building dangerous AIs, like asking governments to make it illegal to build dangerous AIs, were considered gauche.

Considered by whom? Rationalists? The public? The public would not have been so supportive before ChatGPT, because most everybody didn't expect general AI so soon, if they thought about the topic at all. It wasn't an option at the time. Talking about this at all was weird, or at least niche, certainly not something one could reasonably expect politicians to care about. That has changed, but only recently.

I don't particularly disagree with your prescription in the short term, just your history. That said, politics isn't exactly our strong suit.

But even if we get a pause, this only buys us some time. In the long(er) term, I think either the Singularity or some kind of existential catastrophe is inevitable. Those are the attractor states. Our current economic growth isn't sustainable without technological progress to go with it. Without that, we're looking at civilizational collapse. But with that, we're looking at ever widening blast radii for accidents or misuse of more and more powerful technology. Either we get smarter about managing our collective problems, or they will eventually kill us. Friendly AI looked like the way to do that. If we solve that one problem, even without world cooperation, it solves all the others for us. It's probably not the only way, but it's not clear the alternatives are any easier. What would you suggest?

I can think of three alternatives.

First, the most mundane (but perhaps most difficult), would be an adequate world government. This would be an institution that could easily solve climate change, ban nuclear weapons (and wars in general), etc. Even modern stable democracies are mostly not competent enough. Autocracies are an obstacle, and some of them have nukes. We are not on track to get this any time soon, and much of the world is not on board with it, but I think progress in the area of good governance and institution building is worthwhile. Charter cities are among the things I see discussed here.

Second might be intelligence enhancement through brain-computer interfaces. Neuralink exists, but it's early days. So far, it's relatively low bandwidth. Probably enough to restore some sight to the blind and some action to the paralyzed, but not enough to make us any smarter. It might take AI assistance to get to that point any time soon, but current AIs are not able, and future ones will be even more of a risk. This would certainly be of interest to us.

Third would be intelligence enhancement through biotech/eugenics. I think this looks like encouraging the smartest to reproduce more rather than the misguided and inhumane attempts of the past to remove the deplorables from the gene pool. Biotech can speed this up with genetic screening and embryo selection. This seems like the approach most likely to actually work (short of actually solving alignment), but this would still take a generation or two at best. I don't think we can sustain a pause that long. Any anti-AI enforcement regime would have too many holes to work indefinitely, and civilization is still in danger for the other reasons. Biological enhancement is also something I see discussed on LessWrong.

If LW takes this route, it should be cognizant of the usual challenges of getting involved in politics. I think there's a very good chance of evaporative cooling, where people trying to see AI clearly gradually leave, and are replaced by activists. The current reaction to OpenAI events is already seeming fairly tribal IMO.

Well I asked this https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/X9Z9vdG7kEFTBkA6h/what-could-a-policy-banning-agi-look-like but roughly no one was interested--I had to learn about "born secret" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Born_secret from Eric Weinstein in a youtube video.

FYI, while restricting compute manufacture is I would guess net helpful, it's far from a solution. People can make plenty of conceptual progress given current levels of compute https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/sTDfraZab47KiRMmT/views-on-when-agi-comes-and-on-strategy-to-reduce . It's not a way out, either. There are ways possibly-out. But approximately no one is interested in them.

I think this is the sort of conversation we should be having! [Side note: I think restricting compute is more effective than restricting research because you don't need 100% buy in.

- it's easier to prevent people from manufacturing semiconductors than to keep people from learning ideas that fit on a napkin

- It's easier to prevent scientists in Eaccistan from having GPUs than to prevent scientists in Eaccistan from thinking.

The analogy to nuclear weapons is, I think, a good one. The science behind nuclear weapons is well known -- what keeps them from being built is access to nuclear materials.

(Restricting compute also seriously restricts research. Research speed on neural nets is in large part bounded by how many experiments you run rather than ideas you have.)]

The science behind nuclear weapons is well known -- what keeps them from being built is access to nuclear materials.

This is not true for AGI.

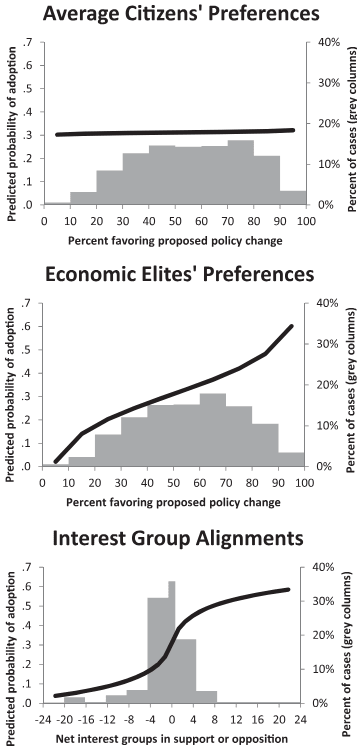

There's a paper from ten years ago, "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens", which says that public opinion has very little effect on government, compared to the opinion of economic elites. That might be a start in figuring out what you can and can't do with that 40%.

compared to the opinion of economic elites

Note that's also a way of saying the economic elites had little effect too, in the "Twice nothing is still nothing" sort of way: https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/spencer-greenberg-stopping-valueless-papers/#importance-hacking-001823

...But one example that comes to mind is this paper, “Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens.” The basic idea of the paper was they were trying to see what actually predicts what ends up happening in society, what policies get passed. Is it the view of the elites? Is it the view of interest groups? Or is it the view of what average citizens want?

And they have a kind of shocking conclusion. Here are the coefficients that they report: Preference of average citizens, how much they matter, is 0.03. Preference of economic elites, 0.76. Oh, my gosh, that’s so much bigger, right? Alignment of interest groups, like what the interest groups think, 0.56. So almost as strong as the economic elites. So it’s kind of a shocking result. It’s like, “Oh my gosh, society is just determined by what economic elites and interest groups think, and not at all by average citizens,” right?

Rob Wiblin: I remember this paper super well, because it was covered like wall-to-wall in the media at some point. And I remember, you know, it was all over Reddit and Hacker News. It was a bit of a sensation.

Spencer Greenberg: Yeah. So this often happens to me when I’m reading papers. I’m like, “Oh, wow, that’s fascinating.” And then I come to like a table in Appendix 7 or whatever, and I’m like, “What the hell?”

And so in this case, the particular line that really throws me for a loop is the R² number. The R² measures the percentage of variance that’s explained by the model. So this is a model where they’re trying to predict what policies get passed using the preferences of average citizens, economic elites, and interest groups. Take it all together into one model. Drum roll: what’s the R²? 0.07. They’re able to explain 7% of the variance of what happens using this information.

Rob Wiblin: OK, so they were trying to explain what policies got passed and they had opinion polls for elites, for interest groups, and for ordinary people. And they could only explain 7% of the variation in what policies got up? Which is negligible.

Spencer Greenberg: So my takeaway is that they failed to explain why policies get passed. That’s the result. We have no idea why policies are getting passed.

Yes, I did read the paper. And those are still extremely small effects and almost no predictability, no matter how you graph them (note the axis truncation and sparsity), even before you get into the question of "what is the causal status of any of these claims and why we are assuming that interest groups in support precede rather than follow success?"

I think the "crux" is that, while policy is good to have, it's fundamentally a short-term delaying advantage. The stuff will get built eventually no matter what, and any delay you can create before it's built won't really be significant compared to the time after it's built. So if you have any belief that you might be able to improve the outcome when-not-if it's built, that kind of dominates.

Suppose there were some gears in physics we weren't smart enough to understand at all. What would that look like to us?

It would look like phenomena that appears intrinsically random, wouldn't it? Like imagine there were a simple rule about the spin of electrons that we just. don't. get. Instead noticing the simple pattern ("Electrons are up if the number of Planck timesteps since the beginning of the universe is a multiple of 3"), we'd only be able to figure out statistical rules of thumb for our measurements ("we measure electrons as up 1/3 of the time").

My intuitions conflict here. One the one hand, I totally expect there to be phenomena in physics we just don't get. On the other hand, the research programs you might undertake under those conditions (collect phenomena which appear intrinsically random and search for patterns) feel like crackpottery.

Maybe I should put more weight on superdetermism.

If you do set out on this quest, Bell's inequality and friends will at least put hard restrictions on where you could look for a rule underlying seemingly random wave function collapse. The more restricted your search, the sooner you'll find a needle!

"When you talk about the New York Times, rational thought does not appear to be holding the mic"

--Me, mentally, to many people in the rationalist/tech sphere since Scott took SlateStarCodex down.