I think this essay is going to be one I frequently recommend to others over the coming years, thanks for writing it.

But in the end, deep in the heart of any bureaucracy, the process is about responsibility and the ways to avoid it. It's not an efficiency measure, it’s an accountability management technique.

This vaguely reminded me of what Ivan Vendrov wrote in Metrics, Cowardice, and Mistrust. Ivan began by noting that "companies optimizing for simple engagement metrics aren’t even being economically rational... so why don't they?" It's not because "these more complex things are hard to measure", if you think about it. His answer is cowardice and mistrust, which lead to the selection of metrics "robust to an adversary trying to fool you":

But the other reason we use metrics, sadly much more common, is due to cowardice (sorry, risk-aversion) and mistrust.

Cowardice because nobody wants to be responsible for making a decision. Actually trying to understand the impact of a new feature on your users and then making a call is an inherently subjective process that involves judgment, i.e. responsibility, i.e. you could be fired if you fuck it up. Whereas if you just pick whichever side of the A/B test has higher metrics, you’ve successfully outsourced your agency to an impartial process, so you’re safe.

Mistrust because not only does nobody want to make the decision themselves, nobody even wants to delegate it! Delegating the decision to a specific person also involves a judgment call about that person. If they make a bad decision, that reflects badly on you for trusting them! So instead you insist that “our company makes data driven decisions” which is a euphemism for “TRUST NO ONE”. This works all the way up the hierarchy - the CEO doesn’t trust the Head of Product, the board members don’t trust the CEO, everyone insists on seeing metrics and so metrics rule.

Coming back to our original question: why can’t we have good metrics that at least try to capture the complexity of what users want? Again, cowardice and mistrust. There’s a vast space of possible metrics, and choosing any specific one is a matter of judgment. But we don’t trust ourselves or anyone else enough to make that judgment call, so we stick with the simple dumb metrics.

This isn’t always a bad thing! Police departments are often evaluated by their homicide clearance rate because murders are loud and obvious and their numbers are very hard to fudge. If we instead evaluated them by some complicated CRIME+ index that a committee came up with, I’d expect worse outcomes across the board.

Nobody thinks “number of murders cleared” is the best metric of police performance, any more than DAUs are the best metric of product quality, or GDP is the best metric of human well-being. However they are the best in the sense of being hardest to fudge, i.e. robust to an adversary trying to fool you. As trust declines, we end up leaning more and more on these adversarially robust metrics, and we end up in a gray Brezhnev world where the numbers are going up, everyone knows something is wrong, but the problems get harder and harder to articulate.

His preferred solution to counteracting this tendency to use adversarially robust but terrible metrics is to develop an ideology to promote mission alignment:

A popular attempt at a solution is monarchy. ... The big problem with monarchy is that it doesn’t scale. ...

A more decentralized and scalable solution is developing an ideology: a self-reinforcing set of ideas nominally held by everyone in your organization. Having a shared ideology increases trust, and ideologues are able to make decisions against the grain of natural human incentives. This is why companies talk so much about “mission alignment”, though very few organizations can actually pull off having an ideology: when real sacrifices need to be made, either your employees or your investors will rebel.

While his terminology feels somewhat loaded, I thought it natural to interpret all your examples of people breaking rules to get the thing done in mission alignment terms.

Another way to promote mission alignment is some combination of skilful message compression and resistance to proxies, which Eugene Wei wrote about in Compress to impress about Jeff Bezos (monarchy in Ivan's framing above). On the latter, quoting Bezos:

As companies get larger and more complex, there’s a tendency to manage to proxies. This comes in many shapes and sizes, and it’s dangerous, subtle, and very Day 2.

A common example is process as proxy. Good process serves you so you can serve customers. But if you’re not watchful, the process can become the thing. This can happen very easily in large organizations. The process becomes the proxy for the result you want. You stop looking at outcomes and just make sure you’re doing the process right. Gulp. It’s not that rare to hear a junior leader defend a bad outcome with something like, “Well, we followed the process.” A more experienced leader will use it as an opportunity to investigate and improve the process. The process is not the thing. It’s always worth asking, do we own the process or does the process own us? In a Day 2 company, you might find it’s the second.

I wonder how all this is going to look like in a (soonish?) future where most of the consequential decision-making has been handed over to AIs.

I like the phrase "Trust Network" which I've been hearing here and there.

TRUST NO ONE seems like a reasonable approximation of a trust network before you actually start modelling a trust network. I think it's important to think of trust not as a boolean value, not "who can I trust" or "what can I trust" but "how much can I trust this" and in particular, trust is defined for object-action pairs. I trust myself to drive places since I've learned how and done so many times before, but I don't trust myself to pilot an airplane. Further, when I get on an airplane, I don't personally know the pilot, yet I trust them to do something I wouldn't trust myself to do. How is this possible? I think there is a system of incentives and a certain amount of lore which informs me that the pilot is trustworthy. This system which I trust to ensure the trustworthiness of the pilot is a trust network.

When something in the system goes wrong, maybe blame can be traced to people, maybe just to systems, but in each case, something in the system has gone wrong, it has trusted someone or some process that was not ideally reliable. That accountability is important for improving the system. Not because someone must be punished, but because, if the system is to perform better in the future, some part of it must change.

I agree with the main article that accountability sinks protect individuals from punishment for their failures are often very good. In a sense, this is what insurance is, which is a good enough idea that it is legally enforced for dangerous activities like driving. I think accountability sinks in this case paradoxically make people less averse to making decisions. If the process has identified this person as someone to trust with some class of decision, then that person is empowered to make those decisions. If there is a problem because of it, it is the fault of the system for having identified them improperly.

I wonder if anyone is modelling trust networks like this. It seems like I might be describing reliability engineering with bayes-nets. In any case, I think it's a good idea and we should have more of it. Trace the things that can be traced and make subtle accountability explicit!

It’s always worth asking, do we own the process or does the process own us?

That's a nice shortcut to explain the distinction between "a process imposed upon yourself" vs. "a process handed to you from above".

Fantastic post, an overreliance on process can end up with an inflexible and stiff system. I'd like to add an example I've personally encountered in my own life, the "Zero Tolerance Policy" of schools back in the mid 2000s. I was often bullied in middle school and at one point in my life a kid was pulling on my coat while I had something in my hand. It slipped out and hit them, which caused them to beat me to the floor and punch me in the face repeatedly until the teachers stopped them. The school of course responded to their violence with a suspension (as is proper) but also tried to suspend me as well until my dad made it clear that he would not back down on the matter and demanded to see the tapes. The school folded and I was not suspended. If my father had not been such a fierce advocate, I would have been punished for the crime of being a victim. Human systems are not created with a perfect vision of the future being followed by robots, it simply can not predict every exception in every way and even if it could it would be too confusing to follow.

And yet I think this goes too hard on process and procedure in some ways. You acknowledge this with how society would collapse without rules and process, but I think it's better to look at the problem as one of tradeoffs. The limits on human flexibility are often a negative, but time and time again we flock to them. Why is that? Because without clear rules and procedure, humans can be really stupid, emotional and egotistical.

Rules are accountability sinks in part because they're the ones that create accountability to begin with. A society that follows its own rules is a society that builds up credibility overtime. As an example there are issues with the American legal system but I would much prefer to have the worst American judge looking over my case than the best North Korean one. The worst American judge is still at least somewhat accountable to the rules, and I can appeal and appeal upwards quite a bit. If I upset a political leader like a mayor, senator or president, it's difficult for them to corrupt not just the worst American judge but all the judges throughout the appeals process. The best North Korean judge however has no such process. If Kim Jong Un tells him to give me the death penalty, then I die.

This exists because of rules and process. While America has not been literally perfect and will likely never be literally perfect, I can still generally trust in the system. I can generally trust that a prosecutor must bring more evidence to a trial than "I don't like him and want him to be guilty", I can generally trust that a judge won't sentence me just because he doesn't like my face. And I can generally trust that the rest of government will do the same, that my mayor will not lean over to his police buddies and have me thrown in jail without a shred of proof. And even if that does happen, I can generally trust that when the court says "Let them go", I will be let out. I can do all of this because America has rules and process and obeys them the large majority of the time.

Ultimately rules are just words on paper, but our collective trust and faith in them creates a stable society where they do generally get enforced. Not perfectly, but better than most other nations both nowadays and in history. Sometimes rules get distorted, sometimes they get abused, sometimes they mandate things that shouldn't happen but I can at least trust that they will *generally* be followed and violators will *generally* be punished when possible and thus I can feel safe and assured that if tomorrow I insult my mayor, my governor, my senator, my local police chief, or my president that their hand can not easily reach out and slay me with their power. We can and should work on seeking a better balance when possible, but it is precisely this inflexibility that keeps me safe, and that means we trade off that sometimes rules take a little bit too much away. Thhanks to rules, I can also generally expect my bully to be punished for punching me.

And at the very least, I can predict the actions of a rules and process addict even if they are bad rules. Even in a county where you get the death penalty for speaking out against the Dear Leader, as long as they follow process you can at least know the outcome before you speak out. Unlike in many of those old school monarchies where the rules were shifting and vague based off the current feelings of the monarch.

A story of ancient China, as retold by a book reviewer:

In 536 BC, toward the end of the Spring and Autumn period, the state of Zheng cast a penal code in bronze. By the standards of the time, this was absolutely shocking, an upending of the existing order—to not only have a written law code, but to prepare it for public display so everyone could read it. A minister of a neighboring state wrote a lengthy protest to his friend Zichan, then the chief minister of Zheng:

“In the beginning I expected much from you, but now I no longer do so. Long ago, the former kings consulted about matters to decide them but did not make penal codes, for they feared that the people would become contentious. When they still could not manage the people, they fenced them in with dutifulness, bound them with governance, employed them with ritual propriety, maintained them with good faith, and fostered them with nobility of spirit. They determined the correct stipends and ranks to encourage their obedience, and meted out strict punishments and penalties to overawe them in their excesses. Fearing that that still was not enough, they taught them loyalty, rewarded good conduct, instructed them in their duties, employed them harmoniously, supervised them with vigilance, oversaw them with might, and judged them with rigor. Moreover, they sought superiors who were sage and principled, officials who were brilliant and discerning, elders who were loyal and trustworthy, and teachers who were kind and generous. With this, then, the people could be employed without disaster or disorder. When the people know that there is a code, they will not be in awe of their superiors. Together they bicker, appeal to the code, and seek to achieve their goals by trying their luck. They cannot be governed.

“When there was disorder in the Xia government, they created the ‘Punishments of Yu.’ When there was disorder in the Shang government, they created the ‘Punishments of Tang.’ When there was disorder in the Zhou government, they composed the ‘Nine Punishments.’ These three penal codes in each case arose in the dynasty’s waning era. Now as chief minister in the domain of Zheng you, Zichan, have created fields and ditches, established an administration that is widely reviled, fixed the three statutes, and cast the penal code. Will it not be difficult to calm the people by such means? As it says in the Odes,

Take the virtue of King Wen as a guide, a model, a pattern;

Day by day calm the four quarters.

And as it says elsewhere,

Take as model King Wen,

And the ten thousand realms have trust.In such an ideal case, why should there be any penal codes at all? When the people have learned how to contend over points of law, they will abandon ritual propriety and appeal to what is written. Even at chisel’s tip and knife’s edge they will contend. A chaotic litigiousness will flourish and bribes will circulate everywhere.

“Will Zheng perhaps perish at the end of your generation? I have heard that ‘when a domain is about to fall, its regulations are sure to proliferate.’ Perhaps this is what is meant?”

Zichan wrote back:

“It is as you have said, sir. I am untalented, and my good fortune will not reach as far as my sons and grandsons. I have done it to save this generation.”

Maybe I'm just misunderstanding the structure of the essay, but I'm a bit confused by the second half of this essay — you begin to argue that there are benefits to designing accountability sinks correctly, but it seems like most of your subsequent examples to support this involve someone disobeying the formal process and taking responsibility!

- The ER doctor skips process, turns over triage, and takes responsibility. His actions are defended by people using out-of system reasoning.

- The ATC skips process, comes back, and takes responsibility. Her actions are defended by people using out-of system reasoning.

etc for Healthcare.gov, Boris Johnson, etc. They were operating in the context of accountability sinks which discouraged the thing they ultimately and rightly chose to do, within the system they would have been forgiven for just following the rules.

Likewise, the free market example given feels like the total opposite of an accountability sink! The person who has the problem is in fact the person who can solve it. The free market does have a classic accountability sink, in the form of externalities, but how it's framed here seems like a perfect everyday example of the buck stopping exactly where it should stop.

The second part begins with: "Second, limiting the accountability if often exactly the thing you want." Maybe I should have elaborated on that, but example is often worth 1000 words...

I did follow that turn, I just am confused by the examples you chose to illustrate it with. The first examples of Bell Labs and VC firms I agree match the claim, but not the subsequent ones.

I am imagining an accountability sink as a situation where the person held responsible has no power over the outcome, shielding a third party. So this is bad as in the airline example (Attendant held responsible by disgruntled passenger, although mostly powerless, this shields corporate structure, problem not resolved), and good as in the VC example (VC firm held responsible by investors for profits, although mostly powerless, this shields startup founders to take risks, problem resolved successfully).

And if this is the frame you're using, then I don't see how the ER doctor and ATC controller examples fit this mold?

Does the Bell Labs example match the claim, though…? My reaction upon reading that one was the same as yours on reading the other anti-examples you listed. OP writes:

The same pattern emerges when looking at successful research institutions such as Xerox PARC, Bell Labs, or DARPA. Time and again, you find a crucial figure in the background: A manager who deliberately shielded researchers from demands for immediate utility, from bureaucratic oversight, and from the constant need to justify their work to higher-ups.

So… there was one specific person—that “crucial figure”—who was accountable to the higher-ups. He “shielded” the researchers by taking all of the accountability on himself! That’s the very opposite of the “accountability sink” pattern, it seems to me…

I read this more like a textbook article and less like a persuasive essay (which are epistemologically harmful imo) so the goal may have been to provide diverse examples, rather than examples which lead you to a predetermined conclusion.

Bad people react to this by getting angry at the gate attendant; good people walk away stewing with thwarted rage.

Shouting at the attendant seems somewhat appropriate to me. They accepted money to become the company's designated point of interface with you. The company has asked you to deal with the company through that employee, the employee has accepted the arrangement, the employee is being compensated for it, and the employee is free to quit if this deal stops being worth it to them. Seems fair to do to the employee whatever you'd do to the company if you had more direct access. (I don't expect it to help, but I don't think it's unfair.)

Extreme example, but imagine someone hires mercenaries to raid your village. The mercenaries have no personal animosity towards you, and no authority to alter their assignment. Is it therefore wrong for you to kill the mercenaries? I'm inclined to say they signed up for it.

They're free to quit in the sense that nobody will stop them. But they need money for food and shelter. And as far as moral compromises go, choosing to be a cog in an annoying, unfair, but not especially evil machine is a very mild one. You say you don't expect the shouting to do any good, so what makes it appropriate? If we all go around yelling at everyone who represents something that upsets us, but who has a similar degree of culpability to the gate attendant, we're going to cause a lot of unnecessary stress and unhappiness.

But they need money for food and shelter.

So do the mercenaries.

The mercenaries might have a legitimate grievance against the government, or god, or someone, for putting them in a position where they can't survive without becoming mercenaries. But I don't think they have a legitimate grievance against the village that fights back and kills them, even if the mercenaries literally couldn't survive without becoming mercenaries.

And as far as moral compromises go, choosing to be a cog in an annoying, unfair, but not especially evil machine is a very mild one.

Shouting at them is a very mild response.

You say you don't expect the shouting to do any good, so what makes it appropriate? If we all go around yelling at everyone who represents something that upsets us, but who has a similar degree of culpability to the gate attendant, we're going to cause a lot of unnecessary stress and unhappiness.

If the mercenary band is much stronger than your village and you have no realistic chance of defeating them or saving anyone, I still think it's reasonable and ethical to fight back and kill a few of them, even if it makes some mercenaries worse off and doesn't make any particular person better off.

At a systemic level, this still acts as an indirect incentive for people to behave better. (Hopefully, the risk of death increases the minimum money you need to offer someone to become a mercenary raider, which makes people less inclined to hire mercenary raiders, which leads to fewer mercenary raids. Similarly, shouting at a secretary hopefully indirectly increases the cost of hiring secretaries willing to stand between you and a person you're harming.)

Though I also kinda feel it's a fair and legitimate response even if you can prove in some particular instance that it definitely won't improve systemic incentives.

I'm inclined to agree, but a thing that gives me pause is something like... if society decides it's okay to yell at cogs when the machine wrongs you, I don't trust society to judge correctly whether or not the machine wronged a person?

Like if there are three worlds

- "Civilized people" simply don't yell at gate attendants. Anyone who does is considered gauche, and "civilized people" avoid them.

- "Civilized people" are allowed to yell at gate attendants when and only when the airline is implementing a shitty policy. If the airline is implementing a very reasonable policy - not just profit maximizing, but good for customers too, even if it sometimes goes bad for individual customers - "civilized people" are not allowed to yell at gate attendants.

- "Civilized people" are allowed to yell at gate attendants when they feel like the airline has wronged them.

...then (broadly speaking) I think right now we live in (1), but I think I'd prefer to live in (2). But I'm worried that if we tried, we'd end up in (3) and I tentatively think I'd like that less.

I think we already live in a world where, if you are dealing with a small business, and the owner talks to you directly, it's considered acceptable to yell at them if they wrong you. This does occasionally result in people yelling at small business owners for bad reasons, but I think I like it better than the world where you're not allowed to yell at them at all.

The main checks on this are (a) bystanders may judge you if they don't like your reasons, and (b) the business can refuse to do any more business with you. If society decides that it's OK to yell at a company's designated representative when the company wrongs you, I expect those checks to function roughly equally well, though with a bit of degradation for all the normal reasons things degrade whenever you delegate.

(The company will probably ask their low-level employees to take more crap than the owners would be willing to take in their place, but similarly, someone who hires mercenaries will probably ask those mercenaries to take more risk than the employer would take, and the mercenaries should be pricing that in.)

Extreme example, but imagine someone hires mercenaries to raid your village. The mercenaries have no personal animosity towards you, and no authority to alter their assignment. Is it therefore wrong for you to kill the mercenaries? I'm inclined to say they signed up for it.

They signed up for it but it is still wrong to kill them. Capture, or knock out to unconsciousness, is an option less permanent and looking better overall - unless it hinders your defence chances significantly; after all, you should continue caring for your goals.

Blameless postmortems are a tenet of SRE culture. For a postmortem to be truly blameless, it must focus on identifying the contributing causes of the incident without indicting any individual or team for bad or inappropriate behavior. A blamelessly written postmortem assumes that everyone involved in an incident had good intentions and did the right thing with the information they had. If a culture of finger pointing and shaming individuals or teams for doing the "wrong" thing prevails, people will not bring issues to light for fear of punishment.

This seems true and important to me. But also... some people really are incompetent or malicious. A blameless postmortem of the XZ backdoor would miss important parts of that story. A blameless postmortem of Royal Air Maroc Express flight 439 would presumably have left that captain still flying? At any rate, as long as "the captain gets fired" is a possible outcome of the postmortem, the captain has incentive to obfuscate. (Which he tried unsuccessfully. Apparently we don't know if he was actually fired though.)

I guess there are cases where "ability to get rid of people" is more important than "risk that people successfully obfuscate important details", and some cases where it's not. I don't know how to navigate these.

Absolutely. In adversarial setting (XZ backdoor) there's no point in relaxing accountability.

The Air Maroc case is interesting though because it's exactly the case when one would expect blameless postmortems to work: The employer and the employee are aligned - neither of them wants the plane to crash and so the assumption of no ill intent should hold.

Reading the article from the point of view of a former SRE... it stinks.

There's something going on there that wasn't investigated. The accident in question is probably just one instance of it, but how did the culture in the airlines got to the point where excessive risk taking and the captain bullying the pilot became acceptable? Even if they fired the captain, the culture would persist and similar accidents would still happen. Something was swept under the carpet here and that may have been avoided if the investigation was careful not to assign blame.

Absolutely. In adversarial setting (XZ backdoor) there's no point in relaxing accountability.

Well, but you don't necessarily know if a setting is adversarial, right? And a process that starts by assuming everyone had good intentions probably isn't the most reliable way to find out.

it's exactly the case when one would expect blameless postmortems to work: The employer and the employee are aligned - neither of them wants the plane to crash and so the assumption of no ill intent should hold.

Not necessarily fully aligned, since e.g. the captain might benefit from getting to bully his first officer, or from coming to work drunk every day, or might have theatre tickets soon after the scheduled landing time, or.... Obviously he doesn't want to crash, but he might have different risk tolerances than his employer.

(Back of the envelope: google says United Airlines employs ~10,000 pilots. If a pilot has a 50-year career, then United has 200 pilot careers every year. Since 2010, they've had about 3000 careers and 9 accidents, no fatalities. That's about 0.3% chance of accident per career. An individual pilot might well want to make choices that have a higher-than-that chance of accident over their career.)

Something was swept under the carpet here and that may have been avoided if the investigation was careful not to assign blame.

Stipulated, but... suppose that the investigators had run a blameless process, the captain had told the truth ("I disabled the EGPWS because it would have been distracting while I deliberately violated a bunch of regulations") with no risk of getting fired, and they found some rot in the culture there. Can they do anything about it? It seems like if the answer is "yes", and if anyone benefits from the current culture, then we're back at people having incentives to lie.

Absolutely agree with everything you've said. The problem of balancing accountability and blamelessness is hard. All I can say is, let's look at how it plays out in the real word. Here, I think, few general trends can be observed as to when less rigid process and less accountability is used:

- In highly complex areas (professors, researchers)

- When creativity is at a premium (dtto, art?)

- When unpredictability is high (emergency medicine, SRE, rescue, flight control, military?)

- When the incentives at the high and low level are aligned (e.g. procurement requires more rigid process, because incentives to prefer friends/family are just too high)

Few examples:

When working at an assembly line, the environment is deliberately crafted to be predictable, creativity hurts rather than helps. The process is rigid, there's no leeway.

At Google, there are both SREs and software engineers. The former are working in a highly unpredictable environment, the latter are not. From my observation, the former have both much less rigid processes and are blamed much less when things go awry.

Military is an interesting example which I would one day like to look more deeply into... As far as I understand the modern western system of units having their own agency instead of blindly following orders can be tracked back to Prussia trying to cope with the defeat by Napoleon. The idea is that a unit gets an goal without the instructions of how to accomplish it. The unit can then act creatively. But while that's the theory, it's hard to implement even to this day. It does not work at all for low-trust armies (Russian army), but even where trust is higher, there tend to be hick-ups. (I've also heard that the OKR system in business management may be descended from this framework, but again, more investigation would be needed.)

To give an example of how disastrously incompetence can interact with the lack of personal accountability in medicine, a recent horrifying case I found was this one:

Doctor indicted without being charged for professional negligence resulting in injury

According to the hospital, Matsui has been involved in a number of medical accidents during surgeries he performed over a period of around six months since joining the hospital in 2019, resulting in the deaths of two patients and leaving six others with disabilities.

Matsui was subsequently banned from performing surgery by the hospital and resigned in 2021.

This youtube video goes over the case. An excerpt:

January 22nd: Dr. Chiba's heart sinks when he learns that Matsui has pressured yet another patient into surgery. The patient is 74-year-old Mrs. Fukunaga, and the procedure is a laminoplasty—the same one that left Mrs. Saito paralyzed from the neck down 3 months ago. 'Please let Matsui learn from his mistakes,' Chiba pleads. Knowing that Matsui's grasp of anatomy is tenuous at best, Chiba tries to tell Matsui exactly what he needs to do. 'Drill here,' Chiba says, pointing at a vertebra. Matsui drills, but the patient starts bleeding, constantly bleeding. He calls for more suction, but it's no use; blood is now seeping from everywhere. Matsui is confronted by his greatest weakness: the inability to staunch bleeding, the one skill that every surgeon needs. The operating field is a sea of red. As sweat rolls down his face, Matsui is in complete despair. He knows he has to continue the surgery, so the only thing he can do is pick a spot and drill.

A sickening silence. Even Matsui can feel that something is wrong because his drill hits something that is definitely not bone. Dr. Chiba looks over and lets out a little whimper. Matsui has made the exact same mistake as last time: he's drilled into the spinal cord, and this time the damage is so bad that the patient's nerves look like a ball of yarn. There's actually video footage of this surgery. Yes, it really looks like a ball of yarn, and no, you really don't want to watch it, trust me. The footage ends with Matsui literally just stuffing the nerves back into the hole he drilled and hoping for the best. This was Matsui's most serious surgical error yet, and it would later come back to haunt him. But for now, all he got was a slap on the wrist. A month later, he was back at it. He was going to perform another brain tumor removal—the very first procedure he failed at Ako.

One aspect I found interesting: Japan's defamation laws are so severe that the hospital staff whistleblowers had to resort to drawing a serialized manga about a "fictional" incompetent neurosurgeon to signal the alarm.

That's pretty messed up. This thread is a good examination of the flaws of blame vs blamelessness.

I wonder if we could somehow promote the idea that "outing yourself as incompetent or malevolent" is heroic and venerable. Like with penetration testers, if you could, as an incompetent or malevolent actor, get yourself into a position of trust, then you have found a flaw in the system. If people got big payouts and maybe a little fame if they wanted it for saying. "Oh hey, I'm in this important role, and I'm a total fuck up. I need to be removed from this role", that might promote them doing so, even if they are malevolent but especially if they are incompetent.

Possible flaws are that this would incentivize people to defect sometimes, pretending to be incompetent or malevolent, which is a form of malevolence, but this could get out of control. Also people would be more incentivized to try to get into roles they shouldn't be in, but as with crypto, I'd rather have lots of people trying to break the system to demonstrate it's strength than security through obscurity.

It's not infinitely no-blame. Instead, Just culture would distinguish (my paraphrase):

Blameless behaviour:

Human error: To Err is Human. Human error is inevitable[1] and shall not be punished — not even singling out individuals for additional training.

At-risk behaviour: People can become complacent with experience, and use shortcuts — most often when under time pressure, or to workaround dysfunctional systems. At-risk behaviour shall not be punished, but people should share their lessons and may need to receive additional training.

Blameworthy behaviour:

Reckless behaviour: Someone who knows the risks to be unjustifiedly high, and still acts in that unsafe and norm-deviant manner. This is worthy of discipline, and possibly legal action — it's similar to recklessness in law.

- note that, if the same behaviour were the norm, then just culture no longer considers that person to have acted recklessly! Instead, the norm — a cultural factor in safety — was inadequate. (The legal system may disagree and assign liability nonetheless.)

Malicious behaviour: Similar to the purposeful level of criminal intent. This is worthy of a criminal investigation.

Instead, the focus is on designing the whole system (mechanical and electronic; and human and cultural):

- to be robust to component failures — not just mechanical or electronic components, but also human components. Usually this means redundancy and error-checking, but robustness can also be obtained by simplifying the system and reducing dependencies;

- so that human errors are less likely. For example, an exposed "in case of fire, break glass" fire alarm call point may give frequent false alarms from people accidentally bumping into them, so you add a simple hinged cover that stops these accidental alarms.

From healthcare perspectives, ISMP has a good article, and here is a good table summary.

From an aviation perspective, Eurocontrol has a model policy, which aims to facilitate accident investigations by making evidence collected by accident investigators inadmissible in criminal courts (without preventing prosecutors from independently collecting evidence).

And LessWrong also has a closely-related article by Raemon!

- ^

Human decision-making, too, has a mean time between failures.

Quite an interesting paper you linked:

Conventional wisdom during World War II among German soldiers,

members of the SS and SD as well as police personnel, held that any order given

by a superior officer must be obeyed under any circumstances. Failure to carry

out such an order would result in a threat to life and limb or possibly serious

danger to loved ones. Many students of Nazi history have this same view, even

to this day.

Could a German refuse to participate in the round up and murder of

Jews, gypsies, suspected partisans,"commissars"and Soviet POWs - unarmed

groups of men, women, and children - and survive without getting himself shot

or put into a concentration camp or placing his loved ones in jeopardy?

We may never learn the full answer to this, the ultimate question for

all those placed in such a quandry, because we lack adequate documentation

in many cases to determine the full circumstances and consequences of such a

hazardous risk. There are, however, over 100 cases of individuals whose moral

scruples were weighed in the balance and not found wanting. These individuals

made the choice to refuse participation in the shooting of unarmed civilians or

POWs and none of them paid the ultimate penalty, death! Furthermore,very few

suffered any other serious consequence!

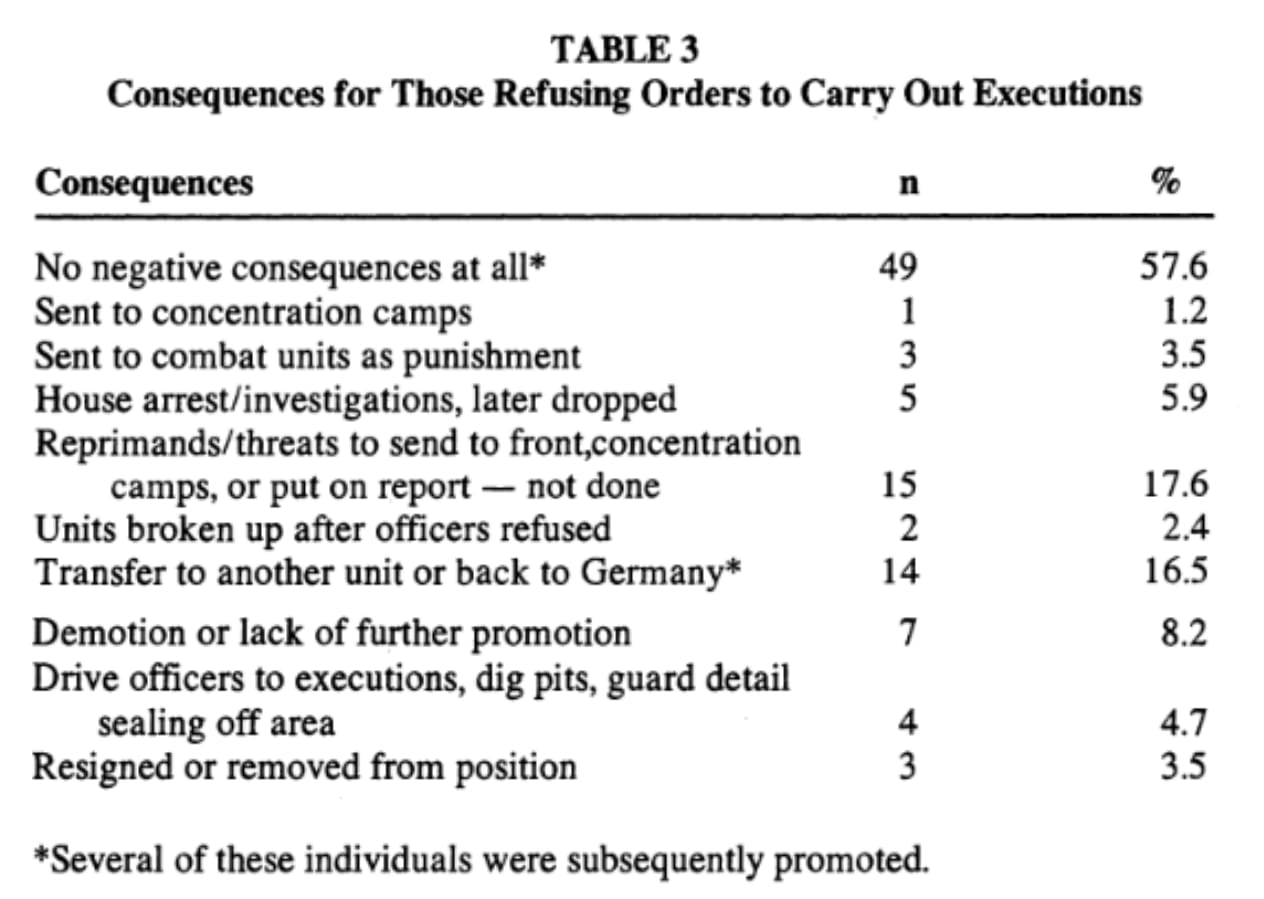

Table of the consequences they faced:

Well, a 5 percent rate of being sent to a concentration camp or combat unit isn't exactly negligible, and a further 17 percent were threatened. So maybe it's correct that these effects are "surprisingly mild", but these stats are more justification for the "just following orders" explanation than I'd have imagined from the main text.

I assumed that there were a large number of unknown cases and that the unknown cases, on average, had less severe consequences. But I haven't read the paper deeply enough to really know this.

I'm not sure that focusing on the outcomes makes sense when thinking about the psychology of individual soldiers. Presumably refusal was rare enough that most soldiers were unaware of what the outcome of refusal was in practice. I think it would probably be rational for soldiers to expect severe consequences absent being aware of a specific case of refusal going unpunished.

I don't know if this is true, but I've heard that when the Nazis were having soldiers round up and shoot people (before the Holocaust became more industrial and systematic), as part of the preparation for having them execute civilians, the Nazi officers explicitly offered their soldiers the chance to excuse themselves (on an individual basis) from having to actually perform the executions themselves with no further consequences.

I guess it was usually not worth bothering with prosecuting disobedience as long as it was rare. If ~50% of soldiers were refusing to follow these orders, surely the Nazi repression machine would have set up a process to effectively deal with them and solved the problem

Relevant section of Project Lawful, on how dath ilan handles accountability in large organizations:

"Basic project management principles, an angry rant by Keltham of dath ilan, section one: How to have anybody having responsibility for anything."

Keltham will now, striding back and forth and rather widely gesturing, hold forth upon the central principle of all dath ilani project management, the ability to identify who is responsible for something. If there is not one person responsible for something, it means nobody is responsible for it. This is the proverb of dath ilani management. Are three people responsible for something? Maybe all three think somebody else was supposed to actually do it.

Several paragraphs collapsed for brevity

Dath ilani tend to try to invent clever new organizational forms, if not otherwise cautioned out of it, so among the things that you get warned about is that you never form a group of three people to be responsible for something. One person with two advisors can be responsible for something, if more expertise is required than one person has. A majority vote of three people? No. You might think it works, but it doesn't. When is it time for them to stop arguing and vote? Whose job is it to say that the time has come to vote? Well, gosh, now nobody knows who's responsible for that meta-decision either. Maybe all three of them think it's somebody else's job to decide when it's time to vote.

The closest thing that dath ilan has to an effective organization which defies this principle is the Nine Legislators who stand at the peak of Governance, voting with power proportional to what they receive from the layers of delegation beneath them. This is in no small part because dath ilan doesn't want Governance to be overly effective, and no private corporations or smaller elements of Governance do that. The Nine Legislators, importantly, do not try to run projects or be at the top of the bureaucracy, there's a Chief Executive of Governance who does that. They just debate and pass laws, which is not the same as needing to make realtime decisions in response to current events. Same with the Court of Final Settlement of which all lower courts are theoretically a hierarchical prediction market, they rule on issues in slowtime, they don't run projects.

Even then, every single Governance-level planetwide law in dath ilan has some particular Legislator sponsoring it. If anything goes wrong with that law, if it is producing stupid effects, there is a particular Legislator to point to, whose job it was to be the person who owned that law, and was supposed to be making sure it didn't have any stupid effects. If you can't find a single particular Legislator to sign off on ownership of a law, it doesn't get to be a law anymore. When a majority court produces an opinion, one person on the court takes responsibility for authoring that opinion.

Every decision made by the Executive branch of government, or the executive structure of a standardly organized corporation, is made by a single identifiable person. If the decision is a significant one, it is logged into a logging system and reviewed by that person's superior or manager. If you ask a question like 'Who hired this terrible person?' there's one person who made the decision to hire them. If you ask 'Why wasn't this person fired?' there's either an identifiable manager whose job it was to monitor this person and fire them if necessary, or your corporation simply doesn't have that functionality.

Keltham is informed, though he doesn't think he's ever been tempted to make that mistake himself, that overthinky people setting up corporations sometimes ask themselves 'But wait, what if this person here can't be trusted to make decisions all by themselves, what if they make the wrong decision?' and then try to set up more complicated structures than that. This basically never works. If you don't trust a power, make that power legible, make it localizable to a single person, make sure every use of it gets logged and reviewed by somebody whose job it is to review it. If you make power complicated, it stops being legible and visible and recordable and accountable and then you actually are in trouble.

The basic sanity check on organizational structure is whether, once you've identified the person supposedly responsible for something, they then have the eyes and the fingers, the sensory inputs and motor outputs, to carry out their supposed function and optimize over this thing they are supposedly responsible for.

Any time you have an event that should've been optimized, such as, for example, notifying Keltham that yet another god has been determined to have been messing with his project, there should be one person who is obviously responsible for that happening. That person needs to successfully be notified by the rest of the organization that Cayden Cailean has been identified as meddling. That person needs the ability to send a message to Keltham.

In companies large enough that they need regulations, every regulation has an owner. There is one person who is responsible for that regulation and who supposedly thinks it is a good idea and who could nope the regulation if it stopped making sense. If there's somebody who says, 'Well, I couldn't do the obviously correct thing there, the regulation said otherwise', then, if that's actually true, you can identify the one single person who owned that regulation and they are responsible for the output.

Sane people writing rules like those, for whose effects they can be held accountable, write the ability for the person being regulated to throw an exception which gets caught by an exception handler if a regulation's output seems to obviously not make sane sense over a particular event. Any time somebody has to literally break the rules to do a saner thing, that represents an absolute failure of organizational design. There should be explicit exceptions built in and procedures for them.

Exceptions, being explicit, get logged. They get reviewed. If all your bureaucrats are repeatedly marking that a particular rule seems to be producing nonsensical decisions, it gets noticed. The one single identifiable person who has ownership for that rule gets notified, because they have eyes on that, and then they have the ability to optimize over it, like by modifying that rule. If they can't modify the rule, they don't have ownership of it and somebody else is the real owner and this person is one of their subordinates whose job it is to serve as the other person's eyes on the rule.

Paragraph collapsed for brevity

'Nobody seems to have responsibility for this important thing I'm looking at' is another form of throwable exception, besides a regulation turning out to make no sense. A Security watching Keltham wander around obviously not knowing things he's been cleared to know, but with nobody actually responsible for telling him, should throw a 'this bureaucratic situation about Keltham makes no sense' exception. There should then be one identifiable person in the organization who is obviously responsible for that exception, who that exception is guaranteed to reach by previously designed aspects of the organization, and that person has the power to tell Keltham things or send a message to somebody who does. If the organizational design fails at doing that, this incident should be logged and visible to the single one identifiable sole person who has ownership of the 'actually why is this part of the corporation structured like this anyways' question.

If one specific person in the Dutch government had been required to give the order to destroy the squirrels, taking full responsibility for the decision, it wouldn't have happened. If there had been an exception handler that employees could notify about the order, it wouldn't have happened.

Promoted to curated: Concrete examples are great. This post is a list of specific examples. Therefore this post is great.

Just kidding, but I do quite like this post. I feel like it does a good job introducing a specific useful concept handle, and explains it with a good mixture of specific examples and general definitions. It doesn't end up too opinionated about how the concept should be used, or some political agenda, and that makes it a good reference post that I expect to link to in a relatively wide range of scenarios.

Thank you!

I liked reading these examples; I wanted to say, it initially seemed to me a mistake not to punish Wascher, whose mistake led to the death of 35 people.

I have a weak heuristic that, when you want enforce rules, costs and benefits aren’t fungible. You do want to reward Wascher’s honesty, but I still think that if you accidentally cause 35 people to die this is evidence that you are bad at your job, and separately it is very important to disincentivize that behavior for others who might be more likely to make that mistake recklessly. There must be a reliable punishment for that kind of terrible mistake.

So you must fire her and bar her from this profession, or fine her half a year’s wages, or something. If you also wish to help her, you should invest in supporting her get into a new line of work with which she can support her family, or something. You can even make her net better off for having helped uncover a critical mistake and saving future lives. But people should know that there was a cost and there will be if they do so in future.

Or at least this is what my weak heuristic says.

This is what the investigation found out (from the Asterisk article):

-

LAX was equipped with ground radar that helped identify the locations of airplanes on the airport surface. However, it was custom built and finding spare parts was hard, so it was frequently out of service. The ground radar display at Wascher’s station was not working on the day of the accident.

-

It was difficult for Wascher to see Intersection 45, where the SkyWest plane was located, because lights on a newly constructed terminal blocked her view.

-

After clearing the USAir plane to land, Wascher failed to recognize her mistake because she became distracted searching for information about another plane. This information was supposed to have been passed to her by another controller but was not. The information transmission hierarchy at the facility was such that the task of resolving missing data fell to Wascher rather than intermediate controllers whose areas of responsibility were less safety-critical.

-

Although it’s inherently risky to instruct a plane to hold on the runway at night or in low visibility, it was legal to do so, and this was done all the time.

-

Although there was an alarm system to warn of impending midair collisions, it could not warn controllers about traffic conflicts on the ground.

-

Pilot procedure at SkyWest was to turn on most of the airplane’s lights only after receiving takeoff clearance. Since SkyWest flight 5569 was never cleared for takeoff, most of its lights were off, rendering it almost impossible for the USAir pilots to see.

Does that make you update your heuristic?

Thank you for the details! I change my mind about the locus of responsibility, and don’t think Wascher seems as directly culpable as before. I don’t update my heuristic, I still think there should be legal consequences for decisions that cause human deaths,

My new guess is that something more like “the airport” should be held accountable and fined some substantial amount of money for the deaths, to go to the victim’s families.

Having looked into it a little more I see they were sued substantially for these, so it sounds like that broadly happened.

Good timing.

Jesus: "I just got done trying to fix this!"

Less jokingly, scapegoating, accountability sinks, liability laundering, declining trust, kakonomics, form an interesting constellation that I feel is under explored for understanding human behavior when part of large systems.

Would you include preference cascades and the formation of common knowledge in the same cluster?

Definitely for preference cascades. For common knowledge I'd say it's about undermining of common knowledge formation (eg meme to not share salary, strong pressure not to name that emperor is naked, etc.)

Sorry about hijacking an only tangentially related thread but I'd love to get your thoughts on ways to accelerate common knowledge formation. This could be technologies or social technologies or something else.

I have a bunch of thoughts around this. Where would be the best place to talk?

I have trouble understanding what's going on in people's heads when they choose to follow policy when that's visibly going to lead to horrific consequences that no one wants. Who would punish them for failing to comply with the policy in such cases? Or do people think of "violating policy" as somehow bad in itself, irrespective of consequences?

Of course, those are only a small minority of relevant cases. Often distrust of individual discretion is explicitly on the mind of those setting policies. So, rather than just publishing a policy, they may choose to give someone the job of enforcing it, and evaluate that person by policy compliance levels (whether or not complying made sense in any particular case); or they may try to make the policy self-enforcing (e.g., put things behind a locked door and tightly control who has the key).

And usually the consequences look nowhere close to horrific. "Inconvenient" is probably the right word, most of the time. Although very policy-driven organizations seem to have a way of building miserable experiences out of parts any one of which might be best described as inconvenient.

I'm not sure I agree who's good and who's bad in the gate attendant scenario. Surely getting angry at the gate attendant is unlikely to accomplish anything, but if (for now; maybe not much longer, unfortunately) organizations need humans to carry out their policies, the humans don't have to do that. They can violate the policy and hope they don't get fired; or they can just quit. The passenger can tell them that. If they're unable to listen to and consider the argument that they don't have to participate in enforcing the policy, I guess at that point they're pretty much NPCs.

I don't know whether we know anything about how to teach this, other than just telling (and showing, if the opportunity arises), or about what works and what doesn't, but I think this is also what I'd consider the most important goal for education to pursue. I definitely intend to tell my kids, as strongly as possible, "You always can and should ignore the rules to do the right thing, no matter what situation you're in, no matter what anyone tells you. You have to know what the right thing is, and that can be very hard, and good rules will help you figure out what the right thing is much better than you could on your own; but ultimately, it's up to you. There is nothing that can force you to do something you know is wrong."

I have trouble understanding what's going on in people's heads when they choose to follow policy when that's visibly going to lead to horrific consequences that no one wants. Who would punish them for failing to comply with the policy in such cases? Or do people think of "violating policy" as somehow bad in itself, irrespective of consequences?

On my model, there are a few different reasons:

- Some people aren't paying enough attention to grok that horrific consequences will ensue, because Humans Who Are Not Concentrating Are Not General Intelligences. Perhaps they vaguely assume that someone else is handling the issue, or just never thought about it at all.

- Some people don't care about the consequences, and so follow the path of least resistance.

- Some people revel in the power to cause problems for others. I have a pet theory that one the strategies that evolution preprogrammed into humans is "be an asshole until someone stops you, to demonstrate you're strong enough to get away with being an asshole up to that point, and thereby improve your position in the pecking order". (I also suspect this is why the Internet is full of assholes--much harder to punish it than in the ancestral environment, and your evolutionary programming misinterprets this as you being too elite to punish.)

- Some people may genuinely fear that they'll be punished for averting the horrific consequences (possibly because their boss falls into the previous category).

- Some people over-apply the heuristic that rules are optimized for the good of all, and therefore breaking a rule just because it's locally good is selfish cheating.

You might also be interested in Scott Aaronson's essay on blankfaces.

I think there's an emperors new clothes effect in chains of command. In every layer, the truth is altered slightly to make things appear a justifiable amount better than they really are, but because there can be so many layers of indirection in the operation of and adherence to policy, the culture can look really different depending on where you find yourself in the class hierarchy. This is especially true with thinking things through and questioning orders. I think people in roles to make policy are often far removed from the mentality that must be adopted to operate in the frantic, understaffed efficiency of front line workers carrying out policy.

"There is nothing that can force you to do something you know is wrong" seems like a very affluent pov. More working class families might suggest advice more like "lower your expectations to lower your stress". I don't know your background though. Do let me know if I'm misunderstanding you.

I am saying you do not literally have to be a cog in the machine. You have other options. The other options may sometimes be very unappealing; I don't mean to sugarcoat them.

Organizations have choices of how they relate to line employees. They can try to explain why things are done a certain way, or not. They can punish line employees for "violating policy" irrespective of why they acted that way or the consequences for the org, or not.

Organizations can change these choices (at the margin), and organizations can rise and fall because of these choices. This is, of course, very slow, and from an individual's perspective maybe rarely relevant, but it is real.

I am not saying it's reasonable for line employees to be making detailed evaluations of the total impact of particular policies. I'm saying that sometimes, line employees can see a policy-caused disaster brewing right in front of their faces. And they can prevent it by violating policy. And they should! It's good to do that! Don't throw the squirrels in the shredder!

I don't think my view is affluent, specifically, but it does come from a place where one has at least some slack, and works better in that case. As do most other things, IMO.

(I think what you say is probably an important part of how we end up with the dynamics we do at the line employee level. That wasn't what I was trying to talk about, and I don't think it changes my conclusions, but maybe I'm wrong; do you think it does?)

sometimes, line employees can see a policy-caused disaster brewing right in front of their faces. And they can prevent it by violating policy. And they should! It's good to do that!

I really like this. Agreed.

Slack is good, and ideally we would have plenty for everyone, but Moloch is not a fan.

I feel like your pov includes a tacit assumption that if there are problems, somewhere there is somebody who, if they had better competence or moral character, could have prevented things from being so bad. I am a fan of Tsuyoku naritai, and I think it applies to ethics as well... I want to be stronger, more skilled and more kind. I want others to want this too. But I also want to acknowledge that, when honestly looking for blame, sometimes it may rest fully in someones character, but sometimes (and I suspect many or most times) the fault exists in systems and our failures of forethought and failures to understand the complexities of large multi state systems and the difficult ambiguity in communication. It is also reasonable to assume both can be at fault.

Something that may be driving me to care about this issue... it seems much of the world today is out for blood. Suffering and looking to identify and kill the hated outgroup. Maybe we have too much population and our productivity can't keep up. Maybe some people need to die. But that is awful, and I would rather we sought our sacrifices with sorrow and compassion than the undeserving bitter hatred that I see.

I believe we very well could be in a world where every single human is good, but bad things still happen anyway.

In every layer, the truth is altered slightly to make things appear a justifiable amount better than they really are, but because there can be so many layers of indirection in the operation of and adherence to policy, the culture can look really different depending on where you find yourself in the class hierarchy. This is especially true with thinking things through and questioning orders.

Not sure whather that aligns with your thinking, but Jenifer Pahlka has this nice concept of rigidity cascades. What she means is that a process get ever more rigid as it travels down the hierarchy. What may have been a random suggestion at the highest level becomes a "prefered way of doing thing" a level below that and an "unviolable requirement" at the very bottom of the hierarchy. https://www.eatingpolicy.com/p/understanding-the-cascade-of-rigidity

Yes, I think this is exactly what I am thinking of, but with the implied generality that it applies to all domains, not specifically software as in the article examples, and also with my suggested answers to why it happens not being to avoid responsibility, but rather the closer you are to the bottom of the hierarchy, the more likely you are to be understaffed and overworked in a way that makes it logistically more difficult to spend time thinking about policy, and also to appear more agreeable to management.

Formal processes are mostly beneficial

It feels like you wrote this line first, and nothing you wrote above it was going to change that conclusion. You recite a litany of horrors, grand and mundane, and then ignore them all.

and they’re not going anywhere.

This may be true, but that's no reason to embrace cope the equivalent of "death is what gives life meaning."

I don't agree "the pursuit of happiness is dead" so I guess accountability sinks aren't that big of a problem? Like corporations are not constantly failing due to lack of accountability, for instance the blameless postmortem seems to be working just fine. Maybe we should introduce blameless PMs aka "occasionally accepting an apology" to other layers of society. The problem seems to be too few accountability sinks, not too many.

What's interesting about the whole thing is that it's not a statistical model with a single less/more accountability slider. There's actual insight into the mechanism, which in turn allows to think about the problem qualitatively, to consider different kinds of sinks, which of them should be preferred and under which circumstances etc.

Well not to dig in or anything but if I have a chance to automate something I'm going to think of it in terms of precision/recall/long tails, not in terms of the joy of being able to blame a single person when something goes wrong. There are definitely better coordination/optimization models than "accountability sinks." I don't love writing a riposte to a concept someone else found helpful but it really is on the edge between "sounds cool, means nothing" and "actively misleading" so I'm bringing it up.

The Nuremberg defense discussion is sketch. The author handles it OK but I don't like grouping it in with these other accountability sinks. "Oh the Holocaust is just an accountability sink" is rationalism at its most self-caricature. Like maybe an insight from being an SRE at Google shouldn't immediately be cast into a new history of Germany 1930-1945. Just, like, be careful, when forming new mental models about the Holocaust from someone who worked on keeping Gmail up for a few years.

More object level I don't exactly share OP's discomfort with the Nuremberg defense. It seems like many people are culpable for Nazi Germany on the basis of hateful opinions they participated in and acted on, and its' hard to figure out how to balance justice, mercy, and moving forward, but not for any reason that is elucidated by the concept of an accountability sink. It's really not hard to agree with something like "Hitler is more culpable than a guy who voted for Hitler." Punishing everyone in Germany for WWI backfired -- so there seems to be a loose coupling of justice and progress, but the problem isn't lack of knowing who's culpable.

In the rest of this comment, I'm talking in detail about some of my mental models of the Holocaust. If you think it might be more upsetting to you than helpful, please don't read it.

It seems like you might be pointing out that there is a significant difference in the badness of hundreds of thousands of people being systematically murdered and a web server going down... which should be obvious, but I'm not sure about your actual critique of the concept of an "accountability sink". The concept seems important and valuable to me.

I recall reading about how gas chambers were designed so that each job was extremely atomized, allowing each person to rationalize their culpability. One person just lead people into a room and shut the door. Another separate person loaded a chamber of poison, someone else just operates the button that releases that poison. A completely different door is used for people who remove the bodies ensuring that the work teams dealing with putting living people in are separate from those working on taking dead people out. It really does seem like the process was well designed from the perspective of an accountability sink and understanding that seems meaningful.

You do know the Nuremberg defense is bad and wrong and was generally rejected right? Nazis are bad, even if their boss is yet another Nazi, who is also bad. If it's an "accountability sink" it's certainly one that was solved by holding all of them accountable. I don't share your "vague feeling of arbitrariness," nor did the Allies. Nazis pretended they're good people by building complicated contraptions to suppress their humanity, I'm aware, that's what makes it a defense, and we reject it.

If accountability sink lends credence to Nuremberg defense then it's a bad concept. If you want to use the concept you would say "while an accountability sink, the right thing to do is hold everyone accountable," in which case I'm not sure what the word "sink" is doing. It sounds like we're deciding whether to hold someone accountable then doing so.

It seems you might be worried the concept "accountability sink" could be use to excuse crimes that should not be excused. I'll suggest that if improperly applied, they could be used for that, but if properly applied they are more beneficial than this risk.

In your earlier comment you suggested that what is being said here is "Oh the Holocaust is just an accountability sink". That suggests you may be thinking of this in a True/False way rather than a complex system dynamics kind of way. I don't think anyone here agrees with "the Holocaust was an accountability sink" but rather, people would agree with "there were accountability sinks in the Holocaust, without which, more people would have more quickly resisted rather than following orders".

I think you can view punishment at least two ways. (a) As a way of hurting those who deserve to be hurt because they are bad. (b) As a way to signal to other people who would commit such a crime that they should not because the outcome for them will be bad.

I can't fault fault people who feel a desire for (a), but I feel it should be viewed as perverse, like children who enjoy feeling powerful by playing violent video games, these are not the people who I want as actual soldiers.

I feel (b) is a reasonable part our goal "prevent bad things from happening". But people are only so influenced by fear of punishment. They may still defect if: - they think they can get away with it, - they are sufficiently desperate, - they believe what they are doing is ideologically right. So if we want to go further with influencing those actors we need to understand those cases, each of which I think includes some form of not thinking what they are doing is bad, and accountability sinks may form a part of that.

You may be concerned that focus on accountability sinks will lead to letting those who should be punished off the hook, but we could flip that. Maybe we punish everyone who has any involvement with an accountability sink because they should have known better. I am currently poorer than I would have been if I had been more willing to engage with the nebulously evil society I was born into. I would feel some vindication if, for example, everyone who bought designer clothes manufactured in sweat shops was charged with a crime. I don't think this is going to happen for practical reasons, but I think your impression that "sink" implies that we actually won't hold people accountable is wrong, it is more that people in these situations don't feel accountable and it's hard to tell who actually is accountable. I think "everyone is accountable when engaging with an accountability sink" is a reasonable perspective.

Looking at "accountability sinks" is good for predicting when people might engage in mass harmful systems. Predicting this is good since we want to prevent it, and educating people to watch out for accountability sinks because if you willingly engage with an accountability sink you are accountable and will be tried as such.

Note that this does have implications for capitalism / market based society. There are many products that don't have a 3rd party certificate showing it was audited and isn't making use of accountability sinks to benefit from criminal things like illegal working conditions or compensation, or improper waste disposal. Buying such products should rightly be illegal. But unfortunately this will raise the cost of legal products forcing many people who are currently near the poverty line below it. This is not something that should be taken lightly either.

First, as already mentioned, formal processes are, more often than not, good and useful. They increase efficiency and safety. They act as a store of tacit organizational knowledge. Getting rid of them would make the society collapse.

You could argue, the judicial branch within the Constitution was designed to limit accountability (tenuring Supreme Court justices for life) so that they could judge freely; and that a societal amnesia is why we are skeptical of that policy again.

While it’s easy to see how a rigid procedure can strip agency from frontline workers—whether at Schiphol Airport in 1999 or on an airline gate—there’s a deeper point worth emphasizing: processes are not villains in themselves but the tools we use to achieve collective goals.

At their best, formalized workflows capture institutional knowledge, ensure consistency, and guard against the whims of any single individual. When they “misfire” in rare edge cases, that usually means one of two things: either the process wasn’t designed to handle that scenario, or the mechanisms for handling exceptions were missing or poorly defined. In other words, a process gone awry doesn’t discredit the very idea of process; it reveals gaps in its design.

Far from being an antithesis to human judgment, exception-handling should be built into every robust system. A well-constructed process explicitly defines who has the authority to deviate, under what circumstances, and how that deviation is documented and reviewed. If you leave out that “escape hatch,” you don’t just create an accountability sink—you create brittle machinery that can’t adapt when reality steps outside its narrow lanes.

It’s equally dangerous, though, to romanticize the notion of solitary moral actors as the ultimate safeguard. Humans carry their own biases, incomplete information, and emotional states, all of which can lead to inconsistent or unfair decisions. What we really need is a thoughtful blend: processes that enshrine lessons from past cases and guardrails against reckless behavior, alongside well-defined channels for human discretion when the unexpected happens.

In practice, designing accountability back into our systems means three things. First, build clear exception frameworks—authority, scope, documentation, and feedback loops must all be spelled out. Second, adopt blameless post-mortems that treat errors as opportunities to strengthen the process rather than occasions for finger-pointing. Third, maintain transparency through audits and stakeholder reviews so that when the system does stumble, we know exactly where to look and whom to consult.

In the end, we shouldn’t view processes as cold, unfeeling machines set against human ethics. Instead, they are the scaffolding that makes large-scale cooperation possible. A more nuanced perspective admits that processes can fail—but also insists that with the right exception paths and accountability measures, we can harness both the consistency of systems and the wisdom of individuals.

I agree—processes are an efficient way to offload the computation/analysis, from being done in the moment (when time is most valuable) to being done during the planning/designing stages (when time comes very cheaply).

Interesting read, and very weird. my first associations when reading was to Lawfulness - in the GlowFic-Golarion meaning. and for me, this is the essence of responsibility, exactly the opposite of the claim of the post.

the people who responsible to the outcomes look on all possible situations, and choose their own trade-offs. they look on the cost of the trade off, and say they are willing to pay that cost, because the alternative is worst.

what is the opposite of that? culture in which acknowledging cost of policy is political suicide, when all political debates must appear one-sided, when person that say that they willing to pay price x to achieve outcome y is heartless and cruel.

blameless postmortems (or retrospectives, like we do at work after every sprint in agile programming) are part of the process, are the place where we should look on the trade offs and chose them. it doesn't always happen, but mostly, from my point of view, it's lack if processes, not excessive amount of processes, that is the problem.

I think the main part here is, i see process as ultimate form of responsibility. the people who choose it bear it. and you... don't? for some reason?

practically, power buy distance from crime, and people who want to avoid accountability can use the distance for that aim. but i find the whole idea that process absolve from responsibility, instead of transfer and concentrate it in the hands of people who design the process, very weird.

a process imposed upon you from above often incentivizes blind adherence, even when it’s hurting the stated goals

Something something Goodhart’s Law - or rather, hurting the unstated real goals

Something something AGI

This is a cross-post from https://250bpm.substack.com/p/accountability-sinks

— Dan Davies: The Unaccountability Machine

— ibid.

A credit company used to issue plastic cards to its clients, allowing them to make purchases. Each card had the client’s name printed on it.

Eventually, employees noticed a problem: The card design only allowed for 24 characters, but some applicants had names longer than that. They raised the issue with the business team.

The answer they've got was that since only a tiny percentage of people have names that long, rather than redesigning the card, those applications would simply be rejected.

You may be in a perfectly good standing, but you'll never get a credit. And you are not even told why. There's nobody accountable and there's nobody to complain to. A technical dysfunction got papered over with process.

Holocaust researchers keep stressing one point: The large-scale genocide was possible only by turning the popular hatred, that would otherwise discharge in few pogroms, into a formalized administrative process.

For example, separating the Jews from the rest of the population and concentrating them at one place was a crucial step on the way to the extermination.

In Bulgaria, Jews weren't gathered in ghettos or local "labor camps", but rather sent out to rural areas to help at farms. Once they were dispersed throughout the country there was no way to proceed with the subsequent steps, such as loading them on trains and sending them to the concentration camps.

Concentrating the Jews was thus crucial to the success of the genocide. Yet, bureaucrats working on the task haven't felt like they were personally killing anybody. They were just doing their everyday, boring, administrative work.

The point is made more salient when reading about Nuremberg trials. Apparently, nobody was responsible for anything. Everybody was just following the

processorders.To be fair, the accused often acted on their own rather than following the orders. And it turns out that the German soldiers faced surprisingly mild consequences for disobeying unlawful orders. So it's not like the high-ups would be severely hurt if they just walked away or even tried to mitigate the damage.

Yet, the vague feeling of arbitrariness about Nuremberg trials persists. Why blame these guys and not the others? There were literally hundreds of thousands involved in implementing the final solution. The feeling gets even worse when contemplating German denazification trials in 1960's:

— Interview with historian Götz Aly (in German)

At the first glance, this might seem like a problem unique to large organizations. But it doesn't take a massive bureaucracy to end up in the same kind of dysfunction. You can get there with just two people in an informal setting.

Say a couple perpetually quarrels about who's going to do the dishes. To prevent further squabbles they decide to split the chores on weekly, alternating basis.

Everything works well, until one of the spouses falls ill. The dishes pile up in the kitchen sink, but the other spouse does not feel responsible for the mess. It’s not their turn. And yes, there's nobody to blame.

This is what Dan Davies, in his book The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions — and How the World Lost Its Mind, calls "accountability sinks".