I don't see support for the key claim of the article.

This post aims to show that, over the next decade, it is quite likely that most democratic Western countries will become fascist dictatorships - this is not a tail risk, but the most likely overall outcome.

How do we get to "most democratic Western countries"? Which ones should I expect to fall? What's a rough timeline for them falling?

I don't even see what parties are supposed to be those fascist dictatorships. The three main examples given of fascism are "Modi in India, Erdogan in Turkey, and Orban in Hungary".

But:

- Erdogan just narrowly won an election, one in which he was fully expected to step down if defeated. He has repeatedly lost important elections at the local level.

- Modi is a popular leader who is widely expected to win reelection, and yet opposition parties control a great many states. Indian democracy still functions, despite the many failures of the main opposition.

- Hungary also still has elections and viable political opposition.

Other examples include:

- Trump, who has been president without significantly weakening American democracy and whose 3 appointed judges have proven willing to rule against him, particularly

Thanks for the response! Here are some comments:

- India, Turkey, and Hungary are widely referred to as "hybrid regimes" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hybrid_regime), in which opposition still exists and there are still elections, but the state interferes with elections so as to virtually guarantee victory. In Turkey's case, there have been many elections, but Erdogan always wins through a combination of mass arrests, media censorship, and sending his most popular opponent to prison for "insulting public officials" (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63977555). In India's case, Modi is no doubt very popular, but elections are likewise hardly fair when the main opponent is disqualified and sent to prison for "defamation" (insulting Modi). Rather than being voted out, hybrid regimes usually transition to full dictatorships, as has happened in (eg.) Russia, Belarus, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Iran, etc.

- Of course nothing is certain, but France's president is very powerful, and this article discusses in detail how Le Pen could manipulate the system to get a legislative supermajority and virtually unlimited power if elected: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/04/20/france-electio...

In Turkey's case, there have been many elections, but Erdogan always wins through a combination of mass arrests, media censorship, and sending his most popular opponent to prison for "insulting public officials"

You do know that Ekrem Imamoglu was not actually sent to jail, right? He was one of the vice-presidential candidates in the May 2023 election.

Your claims here also ignore the fact that before the May 2023 elections, betting markets expected Erdogan to lose. On Betfair, for example, Erdogan winning the presidential elections was trading at 30c to 35c. Saying that "of course Erdogan would win, he censors his critics and puts them in jail" is a good example of 20/20 hindsight. Can you imagine betting markets giving Putin a 30% chance to win a presidential election in Russia?

It's also not true that Erdogan always wins elections in Turkey. Erdogan's party used to have a majority of seats in the parliament, and over time their share of the vote diminished to the extent that now they don't anymore. To remain in power, Erdogan was compelled to ally with a Turkish nationalist party that had previously been one of his political enemies, and it's only this alliance that has a majority of seats in the parliament now. This also led to noticeable policy shifts in Erdogan's government, most notably when it comes to their attitude towards the Kurds.

It seems to me that you're getting your information from biased sources and your knowledge of the political situation in Turkey is only superficial.

Trump's appointed SCOTUS judges are indeed willing to rule against him and to uphold a coherent legal theory of democracy under the rule of law, which agree or disagree is clearly not equivalent to "whatever my side wants it gets". The same sadly cannot be said of his lower court judges, notably Aileen Cannon, whose presence on the bench in his home district drastically decreases the otherwise high likelihood of his being convicted and imprisoned for having obviously, self-confessedly committed serious crimes. Cannon is exactly the sort of lawless, toadying party hack that fascist dictators-in-making around the world love to appoint to the judiciary, and we should expect lots more of them to be appointed if Trump wins in 2024. This may prove to be the biggest single piece of damage to US democracy in the next decade.

This is a nitpick that doesn't really affect the overall message of the post (which I upvoted), but:

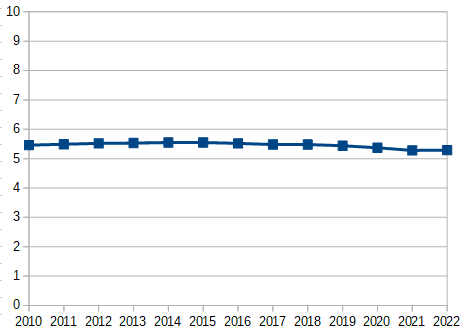

The Economist's Democracy Index shows a sharp decline over the last decade:

That chart has a cut y-axis; the decline looks much less sharp in a graph that shows the full range:

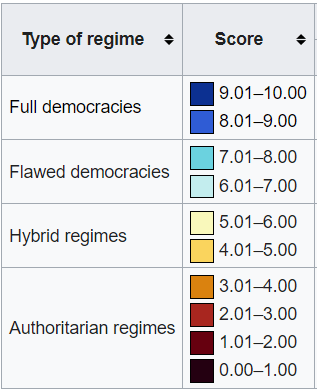

This box from Wikipedia also suggests that the overall average going from 5.55 to 5.3 isn't that significant, as the whole scale is used and everything between 4 and 6 is considered to be within the same category of regime:

+1.

I'm a big fan of extrapolating trendlines, and I think the current trendlines are concerning. But when evaluating the likelihood that "most democratic Western countries will become fascist dictatorships", I'd say these trends point firmly against this being "the most likely overall outcome" in the next 10 years. (While still increasing my worry about this as a tail-risk, a longer-term phenomena, and as a more localized phenomena.)

If we extrapolate the graphs linearly, we get:

- If we wait 10 years, we will have 5 fewer "free" countries and 7 more "non-free" countries. (Out of 195 countries being tracked. Or: ~5-10% fewer "free" countries.)

- If we wait 10 years, the average democracy index will fall from 5.3 to somewhere around 5.0-5.1.

That's really bad. But it would be inconsistent with a wide fascist turn in the West, which would cause bigger swings in those metrics.

(As far as I can tell, the third graph is supposed to indiciate the sign of the derivative of something like a democracy index, in each of many countries? Without looking into their criteria more, I don't know what it's supposed to say about the absolute size of changes, if anything.)

This also makes me confused about the...

In what sense is that a nitpick or something that doesn't affect the message? It's a substantial drag on the message, data that only supports the conclusion if you already have a prior that the conclusion is true.

I meant in the sense that there were quite a few different pieces of evidence presented in the post (e.g. this was one index out of three mentioned), so just pointing out that one of them is weaker than implied doesn't affect the overall conclusion much.

Good point, but also according to Wikipedia "the index includes 167 countries and territories", so small changes in the average are plausibly meaningful.

Man, it is so bizarre living in a red tribe area, and absorbing red tribe perspectives, and then seeing a post like this, and being forced to try to bridge the gap between the two perspectives...

They live in a world where the authoritarian revolution already happened, and the 2020 election being 'obviously stolen' is the greatest indicator of such, and now that the blue elite learned they can get away with using social media censorship and shadowbanning to make any discussion of election security seem extremely low-status, we'll probably never have a real election again

And like, on the one hand, game theory tells me that I really ought to be immediately suspicious of election security that was thought up in the 18th century and not really updated since, especially given my job as someone who tries to secure linux servers and knows security is impossible. and yet on the other hand, even though i'd consider the lesswrong crowd to be far more sympathetic to the red tribe than most intellectual elites and definitely worth assuming good faith, even they reject Trump's complaints about election security as an attempt to manipulate the election itself, not anything to actually do with rea...

I don't actually see very much of an argument presented for the extremely strong headline claim:

This post aims to show that, over the next decade, it is quite likely that most democratic Western countries will become fascist dictatorships - this is not a tail risk, but the most likely overall outcome.

You draw an analogy between the "by induction"/"line go up" AI risk argument, and the increase in far-right political representation in Western democracies over the last couple decades. But the "by induction"/"line go up" argument for AI risk is not the reason one should be worried; one should be worried for specific causal reasons that we expect unaligned ASI to cause extremely bad outcomes. There is no corresponding causal model presented for why fascist dictatorship is the default future outcome for most Western democracies.

Like, yes, it is a bit silly to see "line go up" and plug one's fingers in one's ears. It certainly can happen here. Donald Trump being elected in 2024 seems like the kind of thing that might do it, though I'd probably be happy to bet at 9:1 against. But if that doesn't happen, I don't know why you expect some other Republican candidate to do it, given that none of them seem particularly inclined.

This seems like a strange reaction. If an alien read this post and believed the claims, wouldn't they think fascism was pretty likely very much on the rise? There's global trends, and there's a bunch of specific examples. Do you agree with that?

Maybe you have some reasons that this prima facie evidence isn't actually strong evidence. What are those reasons?

But the "by induction"/"line go up" argument for AI risk is not the reason one should be worried; one should be worried for specific causal reasons that we expect unaligned ASI to cause extremely bad outcomes.

One should be worried because of a combination of specific causal reasons to expect ASI to be very bad for us, plus various lines (compute, capabilities, research investment, research insights, economic benefit) going way up. If the lines weren't going up, there'd be no great reason to expect ASI in the next 50 years with significant probability. We know dictatorships are bad because we've seen it; and we have fascism lines going up.

FWIW I'm not convinced by the article on Haley, having bad conservative policies != being an anti-democratic nut job who wants to rig elections and put all your opponents in jail. She's super unlikely to win, though.

Because there's a big difference between "has unsavory political stances" and "will actively and successfully optimize for turning the US into a fascist dictatorship", such that "far right or fascist" is very misleading as a descriptor.

Noting that the author deleted a critical comment which was somewhat rude but IMO made some reasonable points. That's fair enough, but in conjunction with the way the site handles deletions this strikes me as bad, since there's no way of (a) seeing which user posted the deleted comment (this might be a bug?) (b) examining the text of deleted comments. Together this means that you can't distinguish cases where a post attracts no criticism(an important signal) and cases where there were critical comments that were deleted, and you can't examine deleted criticisms.

I find it ironic that the author of a post warning of the risks of dictatorships becoming more widespread throughout the world has a moderation policy of "deleting anything they judge to be counterproductive".

(Update: I just merged a PR that should fix the issue, i.e. make it clear who's comments got deleted. Should be live in about 7 minutes)

I notice that you cite Freedom House, and Richard Hanania goes into why that NGO in particular is pretty institutionally captured and a biased source. Citing Freedom house is akin to circular reasoning or is too close for comfort with regards to the question of "Democracy". (link) Also, for better or worse every institution of the US is very liberal, including the government (link) so it's hard to imagine how in any real sense the US could become an actual right wing dictatorship.

Furthermore,"The Dictator's Handbook" actually researches this exact question, with an eye toward selectorate theory, on how stable democracies vs dictatorships are, and actually digs into the numbers on this. And the punchline is that if you actually look, once you get past a certain threshold of keys, needed to obtain or stay in power, Democracies become very, very, very stable. And that in the entire history of democracies, no democracy past that threshold has ever backslid into dictatorships, short of being conquered by a foreign power or going completely bankrupt. (It goes without saying the US is well past this point)

The relevant section of The Dictator's Handbook is the following

...Given the complexity of the trade-off between declining private rewards and increased societal rewards, it is useful to look at a simple graphical illustration, which, although based on specific numbers, reinforces the relationships highlighted throughout this book. Imagine a country of 100 people that initially has a government with two people in the winning coalition. With so few essentials and so many interchangeables, taxes will be high, people won’t work very hard, productivity will be low, and therefore the country’s total income will be small. Let’s suppose the country’s income is $100,000 and that half of it goes to the coalition and the other half is left to the people to feed, clothe, shelter themselves and to pay for everything else they can purchase. Ignoring the leader’s take, we assume the two coalition members get to split the $50,000 of government revenue, earning $25,000 a piece from the government plus their own untaxed income. We’ll assume they earn neither more nor less than anyone else based on whatever work they do outside the coalition.

Now we illustrate the consequences of enlarging the coalition

France had a military coup in 1958 followed by 6 months of dictatorship. What threshold had France not passed in 1958 to not count as a full democracy? Does the Dictator's Handbook actually say this?

You write: "Stalinism is also very bad, but is not a major political force in 2023."

Why do you think this? In western countries, the "left" has control of most of the levers of power and influence - eg, look at who gets censored by social media corporations, what sort of stuff academic job applicants have to write to get hired, how much money is spent by governments on left-oriented projects. And there are clear signs of increasing authoritarianism on the left - for example, the Canadian government reaction to the "Freedom Convoy", invoking the Emergencies Act in response to an annoying, but peaceful, protest, and freezing bank accounts of people whose only crime was donating money to the protesters. Some left-wing policies seem almost designed to provoke the right, such as (in the US) giving away hundreds of billions of dollars in student loan forgiveness, and proposing to give away trillions of dollars in "reparations". Such huge wealth transfers break the social compact, and are likely to trigger a conflict that might in the end result in right-wing authoritarians taking power, but presumably are seen by their advocates as more likely to result in a left-wing authoritarian regime.

Most highly educated people lean left, but there really are just very few Stalinists. I quoted a poll above showing that just 8% of Americans would support an AOC hard-left party, and actual Stalinists are a small fraction of that. There's no developed country where tankies get a serious fraction of the vote. See Contrapoints for why communist revolutionaries are super unlikely to take power: https://youtu.be/t3Vah8sUFgI

There are many crazy professors of various stripes, but universities aren't states. They can't shoot you, can't throw you in jail, can't seize your house or business, and are ultimately dependent on government funding to even exist.

Can you explain why "most democratic Western countries will become fascist dictatorships" specifically is the most likely outcome? I'm not quite following the "line go up" reasoning.

Just to give some concrete illustrations: Western Europe has dropped by 0.08 points on the Democracy Index over the last decade. If that happens again, it will fall to 8.28, so about as democratic as the UK is now. Definitely not fascist dictatorship territory!

If we pessimistically assume that Western Europe will decline faster in line with the world average, we get to 8.13, a bit more democratic than France. Also nothing close to a fascist dictatorship.

If Western Europe declines twice as fast as the world average, we get 7.9, a bit more democratic than the US. Three times as fast, we end up just above Belgium. Double that, and we'd be about level with Poland and India: not functioning democracies, but still democratic enough that upsets can happen (e.g. Modi's BJP just lost a major state election in Karnataka). I certainly wouldn't call either of those countries fascist.

Let's assume the decline in democracy speeds up ten times over the next decade: then Western Europe still looks more democratic than Mexico, Ukraine and Peru. A sudden tenfold speed-up in current trends sounds like a tail risk to me, but it doesn't come close to the outcome you're predicting. How do you get to a prediction as strong as that one given the data you've presented?

Thanks for this—I agree that this is a pretty serious concern, particularly in the US. Even putting aside all of the ways in which the end of democracy in the US could be a serious problem from a short-term humanitarian standpoint, I think it would also be hugely detrimental to effective AI policy interventions and cooperation, especially between the US, the UK, and the EU. I'd recommend cross-posting this to the EA Forum—In my opinion, I think this issue deserves a lot more EA attention.

Sam Altman, the quintessential short-timeline accelerationist, is currently on an international tour meeting with heads of state, and is worried about the 2024 election. He wouldn't do that if he thought it would all be irrelevant next year.

Whilst I do believe Sam Altman is probably worried about the rise of fascism and its augmenting by artificial intelligence, I don't see this as evidence of his care regarding this fact. Even if he believed a rise in fascism had no likelihood of occurring; it would still be beneficial for him to pursue the international tour as a means of minimizing x-risks, assuming even that we would see AGI in the next <6 months.

[Facism is] a system of government where there are no meaningful elections; the state does not respect civil liberties or property rights; dissidents, political opposition, minorities, and intellectuals are persecuted; and where government has a strong ideology that is nationalist, populist, socially conservative, and hostile to minority groups.

I doubt that including some of the conditions toward the end makes for a more useful dialogue. Irrespective of social conservatism and hostility directed at minority groups, the risk of fasci...

The Trump section makes a few assumptions that aren't defended. They might be right, they might be wrong, but even the most basic counterarguments aren't addressed.

First, you call questioning the election "overthrowing democracy," which implies that questioning it wasn't in any way justified. What's your prior that an election is sound? This is a genuine question; I'm not sure what's appropriate. Many, many elections throughout human history have been various degrees of rigged. I have no idea what prior to use, and I have no idea what level of fraud/questionable behavior occurs every election, so it's hard to analyze both the prior and the update. That said, you're ascribing bad faith to anyone questioning the results, when most of those truly believe the democratically chosen vote was different. Rigged elections that the media covers up are an equally valid way to abolish democracy, and you provided just as much defense of that claim as you did of yours (none).

If anything, what happened with Gore and Bush in '08 was more egregious than this, and that didn't destroy the republic, at least not to the point of property rights vanishing. Contested elections are par for the course for ...

It was the mechanism and order of the counting which differentiated this election from others. The counts continued long into the night, and into the following days. It was the first election with substantial mail in voting, adding many new attack vectors for fraud.

At about 2am on election night, Trump was a -190 favorite, so not huge, but definitely expected to win. It was certainly unlikely that there were enough votes in the deep blue areas that had yet to be counted to swing the election, although it was no where near prohibitively unlikely.

Then there were the tens of anecdotal reports of various fraudulent or suspicious behaviors at polling and counting sites. To determine what update, if any, these provide, we'd need to know the base rate for them: would there be this many reports for any election where there was sufficient scrutiny? It's very possible, but it's also possible this one really was worse.

So those are the updates. Again, it's unclear how large they are, but they are there.

I can't think of a position I hold for which the election being rigged/sound is actually a crux, other than "I think 99% probability the election was sound is too high," which is why I objected....

Good post. You changed my mind moderately (and somehow did so without presenting many new-to-me facts/arguments, but perhaps by combatting an irrational sense of it couldn't happen here [edit: or more charitably to myself, perhaps just by causing me to think about it]). Focusing on America, thinking about it, I have credence ~40% in a Republican trifecta in 2025 and credence ~30% that Republicans do wild bad stuff in 2025–2026 (mostly from Republican-trifecta worlds but also some from Republican-president-but-no-trifecta worlds). I probably shouldn't try to do anything about this but it's worth Noticing.

only 8% who would vote for a "woke", left-wing AOC party. American conservatives far outnumber liberals, and "woke" policies like defunding the police and affirmative action are very unpopular even in left-wing areas, with the latter being defeated by huge margins in deep-blue California. Hence, even though there are both left-wing and right-wing radicals, it is vastly easier to imagine fascist dictatorship than a "woke" dictatorship, especially as the latter movement now seems to be in decline.

Honestly I think anyone who seriously envisioned a "woke dictatorship" must have had listened way too much to right wing propaganda. The problem with the "woke" movement (which doesn't want to be called that but also refuses to give itself any other name in a desperate and generally failed bid to market itself as the default) is instead exactly that it's this unpopular. It elicits fanatical loyalty in a minority and leaves everyone else baffled or repulsed, dividing the left's ability to push back against the right while offering the latter a perfect strawman to point at for all of left wing ideas. Worse, since lots of people don't have the mental space to separate "this cause is quite im...

Publically, AOC demanding that the Biden administration should engage in authoritarian behaviour provides very little use when she doesn't think that Biden will actually engage in those behavior while at the same time eroding the standards. If a future Trump administration will call for ignoring court orders, you can count on Fox News to air AOC's pronouncements that it's an acceptable tactic.

Even when your ethical system says that sometimes it's worthwhile to break rules because of utilitarian concerns, that doesn't make cases where you call for rules to be broken when you don't expect that actually happen okay. People who do find value in pushing the Overton window to allow for more authoritarian actions are rightfully seen as authoritarians.

Democrat side is overall way more divided on this and has some significant attempts at deescalation.

What do you see as notable attempts at deescalation?

When Trump spoke about putting Hillary in jail for mishandling classified documents, the left talked about it as a huge norm violation but Trump didn't actually follow through.

On the other hand, Democracts are currently hoping pursuing a legal case against Trump for mishandli...

I think this post makes a very important and useful claim, but one that is obscured by the use of the word 'fascism', which -- as the post itself admits -- has for decades had a very charged meaning and has been used in inconsistent ways. It seems as though it is usually used to draw an analogy with the WW2-era Axis powers, but the movements that you're highlighting lack some very important characteristics that those regimes had. Most importantly, under Modi/Orbán/Erdogan, control by the ruling party has never been total; opposition parties control the capital cities in all three countries, and are generally permitted to participate in elections which may not be fair because of media policies but are fairly free. (Also, the movements you highlight are usually not militaristic: Erdogan has had a famously strained relationship with the Turkish military, and most 'populists' in other nations have won running against the entire old elite, which includes the military leadership. They are also rarely or never expansionist.)

But it is very clear that there is a global trend away from rule by a set of 'cosmopolitan' elites (...the details of these elites actually differing a great deal betw...

I do indeed agree this is a major problem even if I'm not sure if I agree with the main claim. The rise of fascism in the last decade and expectation that it will continue is extremely evident; its consequences for democracy are a lot less clear.

The major wrinkle in all of this is in assessing anti-democratic behavior. Democracy indices not a great way of assessing democracy for much the same reason that the Doomsday Clock is a bad way of assessing nuclear risk: they're subjective metrics by (probably increasingly) left-leaning academics and tend to measure a lot of things that I wouldn't classify as democracy (eg rights of women/LGBT people/minorities). This paper found that using re-election rates there has been no evidence of global democratic backsliding. This started quite the controversy in political science; my read on the subsequent discussion is that there is evidence of backsliding, but such backsliding has been fairly modest.

I expect things to get worse as more countries get far-right leaders and those which already have far-right leaders have their democratic institutions increasingly captured by far-right leaders. And yet...a lot of places with far-right leaders contin...

Everyone seems to find the most striking claim here

over the next decade, ... that most democratic Western countries will become fascist dictatorships ... is ... the most likely overall outcome

pretty outlandish. That right-wing, nationalist, conservative parties might win power in a lot of places, seems a reasonable projection (though very far from assured); that they will all turn their countries into "fascist dictatorships" where "there are no meaningful elections" is the outlandish part. That would seem to require something like the Spanish civil war, but throughout Europe and North America, perhaps after a catastrophic collapse of NATO under Trump 2.0 - which might be Putin's dream, and the nightmare of liberal-progressive Americans, but I wouldn't bet on it ever happening.

I noticed one oddity among the references cited. There's this graph about how populists "rarely lose power" peacefully. But if you add up "reached term limits" and "lost free and fair elections", that's actually larger than the other bars. And "still in office" doesn't distinguish between those who have been in office for a year and those who have been there for 25 years.

Furthermore, if you l...

Your link for "The V-Dem Institute's tracker" does not point to that, it points to DWB which is giving its own take on a link to the V-Dem Institute, which in turn is broken so I can't check it. This might be the one intended: https://www.v-dem.net/documents/12/dr_2021.pdf ?

Umberto Eco's list is extremely low quality. Several of its items are stock traits of bad government; if you mean bad government you should say "bad government" and not "fascism". Eco is a rhetorician, please stop citing him as though he's a political scientist.

I think this post is engaged in significant sleight of hand, between claims that a dictator will murder thousands of people, and claims that an abstract rating will decrease below X points. This is aggravated by the fact that the bet has a clause for "If The Economist Democracy Index [...] significantly changes its methodology" when to my knowledge the EDI does not publish its methodology other than a very brief summary.

Side note -- France isn't a great example for your point here "France, for example, is a very old, well-established and liberal democracy." because the Fifth Republic was only established in 1958. It's also notable for giving the president much stronger executive powers compared with the Fourth Republic!

This post would greatly benefit from quantitative forecasts on precise claims that are at least in principle falsifiable.

I also strongly disagree with Erdogan's characterization as a dictator under the definition of "a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections". Perhaps under some "softer" definition, you could classify him as a dictator; but that makes what I said above all the more important. What is a "dictator", and how do we know if we're in a world where "dictatorship" is becoming more widespread?

Russia isn't just closer than the US to being a fascist dictatorship, Russia is a fascist dictatorship by most metrics. It's an autocrat ruled country with a strongly reactionary culture waging a brutal war of conquest on vague bullshit Blood And Soil reasons, it hardly gets more fascist than that.

I don't think 21st century fascism will be the same beat for beat as 1930s one, for example I expect more isolationism and less overt militarism. And yeah, I think it will be mostly "soft" takeovers, just degradation of democracy and possibly limitation of suffrage than actual coups, but even coups could happen (though in the US I would expect one to result in civil war, not a swift and unchallenged takeover).

I'm especially worried about the US going forward. In general presidential republics don't have a good track record. Luckily the US has benefited from strong notions of democratic legitimacy over most of its history. Also, except at the very beginning, for a brief period around the birth of the Republican party, and recently with the introduction of open primaries US political parties haven't had strong ideological partisanship but were mostly very ideologically mixed with most partisanship being over spoils rather than ideology.

In How Democracies Die the authors argue that the most worrying sign for a democracy is an escalating pattern of constitutional hardball where contestants continue to adhere to the written rules but more and more break unwritten norms. Within the last couple of decades we've seen filibusters go from a rarely deployed emergency break to a routine legislative tactic, repeated showdowns over the debt ceiling, a breakdown in norms around supreme court appointees, etc. I don't expect any disaster imminently, but the trends are very bad.

fascism is usually established through a process of democratic backsliding under a populist leader. Essentially, the steps are:

- A charismatic figure emerges to lead a new populist movement, focusing on opposition to the existing political system and its "elites".

- Eventually, average people become dissatisfied with the existing democratic government or leader. Possible reasons range from corruption, to scandals, to economic decline, to a hostile press. As of 2023, most leaders of developed countries have poor approval ratings; opinions vary on whether this is because of changes in the media landscape, or whether society overall just sucks more than it used to.

- In the next election, ordinary people vote for the new populist movement and its leader, and they win democratically.

- Once in power, the new leadership uses state institutions to slowly, one piece at a time, give themselves electoral advantages. They gerrymander districts, take over the media, punish any opposition, and purge or abolish outside institutions or checks on their authority (courts, electoral commissions, local governments, etc.), until democracy is gone.

I'm not sure I follow how this model applies to the examples you ...

Disagree with this and might write up a more thorough response than the one I have in a bit, but for now, here are some manifold markets around this topic area:

The V-Dem Institute's tracker shows that, after widespread growth in democracy during the 1980s and 90s, many more countries are now becoming autocratic than democratic, especially weighted by population:

The V-Dem tracker you show doesn't show "widespread growth in democracy during the 1980s and 90s." It shows a giant explosion all of a sudden starting in 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, and then an equally sudden reversion from about 2000-2004.

It's tracking autocratization, the sign of the direction of change, rather than the magnitude of autocracy or of its rate of change. If the world saw a wave of democratization (as during the USSR's collapse) followed by even a minor systemic reversion to the mean, we would observe this as a giant spike in democratization followed by a giant spike in autocratization.

That said, V-Dem does appear to be a pretty large, serious, thoughtful and data-backed organization, and they have enough examples of autocratization trends in their report that I am updating to say yes, it does look like there's some sort of genuinely concerning autocratization process going on globally.

This post is interesting, but I think it fails to do enough to provide possible causal mechanisms to help folks really think about this. It's a lot of worrying trends, which are good to worry about and an important start, but for me this post is missing something it really needs. So, let me see if I can provide a simple story that might make sense of the trend and give us some clues about how much to worry.

Lately, times have been getting harder for a large number of folks in Western countries. There's less slack in the system. Historically, left-coded positions have existed only when there's sufficient slack, since people don't care about equity or even equality when they aren't sure if they'll have enough grain to survive the winter—all they want is to at least get by. We may not be on the verge of actual famine, but despite rising absolute wealth, relative perceptions of wealth are falling among the working class and some of the professional class. Some of this is real, and some of this is hedonic treadmill, failing to recognize the tide that has lifted all boats. Regardless, the experience of decline, even if it is only relative to other people in the same society, leads to a loss of purpose and a desire for a return to the good old days. The political implications follow naturally.

I think it's great that you took a stand to present your independent observations and relay some information people here may not have encountered on the subject, especially since political discourse is a minor LW taboo. This is good for epistemics IMO.

The key argument for why we'd predict 18+ Western fascisms in the next decade is that we should by default extrapolate current trends, while rejecting the appearance of stability.

I find this contradictory. Why are current derivative of fascism something we should view as "stable" and likely to hold constant over the long term, while the current amount of fascism is something we should view as "unstable" and easy to change?

Obviously, both can't be true - we can't have a stable amount of fascism and also a stable rate of change. I'm just not clear on why you think we ought to assume the rate of change is the statistic that is stable and the absolute level is the statistic that is unstable.

My intuition is the opposite. The level of autocracy appears pretty stable over long time periods in most countries, with occasional shocks and constant wobbles. It seems likely to me that we are having a wobble.

A secondary issue is the underlying caus...

The rise in in authoritarianism in the west is very real and concerning and we should strive to counter it. But I think you overstate some of your points.

In the US, the most recent midterm served as a rebuke to trumpism and election denial. Despite having the highest inflation in recent memory and low favorability scores for biden, democrats actually won a senate seat, barely lost any seats in the house and defeated all AG and governors in swing states that run on election denial. This is not what a normal mid term looks like, and it is certainly not what a midterm in which authoritarians are gaining broader mainstream support would look like. In every special election, democrats overperform too, sometimes to very large extents.

Polls are important to gauge the current public opinion, but especially this far out to an election, they need to be interpreted cautiously. The general election polls are predominantly from low quality and/or republican pollsters. Higher quality pollsters do show Biden leading Trump, but even they don't tell you very much because their numbers of undecided people is so high. This are predominantly people who disapprove of both Biden and Trump, but who have ...

The key thing you don't address is how unelected bodies like the military and the judiciary may pushback against fascists. On January 6th the legislative branch was able to address the issue alone (a kind of blow into your thesis). Anyway, I wouldn't expect Roberts to show up on January 20th to sworn in Trump. And I see at least 5 Justices willing to protect America. The judiciary branch actually is working hard to incarcerate Trump.

Also, you don't address important G7 countries like Japan and the United Kingdom. Because during the far right uprising the C...

A large part of your evidence is that "far-right" parties, like the Sweden democrats, are growing. But ~none of the western parties you mention are running on an explicitly anti-democratic platform, which was a fairly unifying feature of the worst dictatorships throughout history. "Marine Le Pen is a fascist and will start democratic backsliding if she wins" is a pretty odd assumption to just leave unsubstantiated.

AI policy, strategy, and governance involves working with government officials within the political system. This will be very different if the relevant officials are fascists, who are selected for loyalty rather than competence.

The way you tell the story suggests that loyalty to the left is very important to prevent the political right from getting power. This dynamic means that people who sit in powerful chairs are more selected due to loyalty than competence.

The narrative of the importance of fighting fascism led to a media landscape where loyalty to lef...

This conversation might be better if we taboo Hitler and recent politics. On the askhistorians subreddit they have a 50 years rule, and here we say that politics is the mind killer.

In any case, it seems to me that this approach extrapolates current trends, but I suggest that it might be more reliable to look at history for priors. Extrapolation can lead us to predict wild swings, while history puts bounds on the swings and sometimes suggests a return to the mean.

There certainly have been a lot of dictatorships in history and not all of them fascist. But th...

I think this is a bit overstated in terms of likelihood and severity. Political predictions deeply suffer from reference class problems - it's unclear which past events or trends are indicators of future outcomes. Nobody votes in the same election twice. Not legally, at least.

Just my opinion: the concerns are valid but exaggerated.

Perhaps exaggeration is justified in order to get people's attention since most americans are still treating this as a normal election.

I don't see this as being distinct from or better than any typical left wing "republicans are a threat to democracy" article. If there is anything that isn't fit for LW it's this post.

(Disclaimer: This is my personal opinion, not that of any movement or organization.)

This post aims to show that, over the next decade, it is quite likely that most democratic Western countries will become fascist dictatorships - this is not a tail risk, but the most likely overall outcome. Politics is not a typical LessWrong topic, and for good reason:

However, like the COVID pandemic, it seems like this particular trend will be so impactful and so disruptive to ordinary Western life that it will be important to be aware of it, factor it into plans, and try our best to mitigate or work around the effects.

Introduction

First, what is fascism? It's common for every side in a debate to call the other side "fascists" or "Nazis", as we saw during (eg.) the Ukraine War. Lots of things that get called "fascist" online are in fact fairly ordinary, or even harmless. So, to be clear, Wikipedia defines "fascism" as:

Informally, I might characterize "fascism" as:

(The last point is what separates fascism from, say, Stalinism. Stalinism is also very bad, but is not a major political force in 2023.) So by "fascism", I specifically mean a radical change in the basic form of government, not simply a state doing dumb things like making immigration hard or banning Bitcoin. Not all fascists are the same - eg. Mussolini's Italy was initially opposed to Nazi-style racism - but their movements, ideology, rhetoric, and leaders tend to share many common characteristics (see also eg. here).

Fascism is very bad, and therefore, it would be really great if it were unlikely to happen in well-established democracies like the US. Unfortunately, as with AI risk, most arguments for that scenario being unlikely tend to resemble this comic from XKCD:

or this comic about AI risk:

The first argument goes, essentially, that things are basically fine now, and are unlikely to become bad immediately (next week or next month), so therefore we have nothing to worry about. The counterpoint, of course, is that if existing trends continue progressing - and there's no convincing reason why they must stop - the future a few decades from now will become very different from the present. The second argument is that the relevant scenario would be pretty weird by the standards of our current lives (as rich, educated Westerners living in 2023), so we should assume it's unlikely. However, our contemporary lives and civilization are themselves very weird historically (vs. the more typical peasant farming), and there's no fundamental reason why they have to keep on going forever. Indeed, them continuing forever is in some ways a contradiction, since current society relies on economic growth and innovation; we can't coherently forecast "everything stays the same, including the derivatives".

Present Trends

What do the derivatives look like, in terms of countries going fascist? Concepts like "fascism" and "democracy" are tricky to measure, and there are many different standards one could use. However, essentially all the widely used metrics now show a global decline in democracy, and a rapid growth in right-wing authoritarianism and illiberalism, which is sometimes called the "third wave of autocratization". Here is Freedom House's graph of "democracy under siege":

The Economist's Democracy Index shows a sharp decline over the last decade:

The V-Dem Institute's tracker shows that, after widespread growth in democracy during the 1980s and 90s, many more countries are now becoming autocratic than democratic, especially weighted by population:

Very poor areas like Mali and Sudan are prone to military coups, but in more established countries, fascism is usually established through a process of democratic backsliding under a populist leader. Essentially, the steps are:

In a typical post-war, Western democracy, there will be different parties and ideologies, but the leadership of all parties form an elite that shares certain cultural norms. (Scott, Bret Devereaux, and Eliezer all discuss this; Eliezer portrays it as a bad thing, although perhaps he has changed his mind since 2008.) In populist authoritarianism, this group is replaced with a new elite, detached from existing institutions, that lacks interest in ideas like human rights and the rule of law. Hitler is the big example that everyone is familiar with, but he might not be the best one, as Weimar Germany was a strange place and the Nazis were unusual in many ways. Recent, more typical examples that Scott Alexander has written about include Modi in India, Erdogan in Turkey, and Orban in Hungary.

There's nothing inherently partisan about this backsliding process, and past decades have seen various left-wing populist authoritarians, like Huey Long in the US or Hugo Chavez in Venezuela. However, current political trends strongly favor right-wing authoritarianism, national conservatism, or "cultural populism", which "claims that the true people are the native members of the nation-state, and outsiders can include immigrants, criminals, ethnic and religious minorities, and cosmopolitan elites. Cultural populism tends to emphasize religious traditionalism, law and order, sovereignty, and painting migrants as enemies" (from here). The number and strength of right-wing authoritarians now far outmatches left-wing ones.

The political extremism or bad behavior of populist leaders often shocks past politicians, the press, and civil society, and some assume they will be quickly voted out. However, political studies show that populists last much longer in office than traditional leaders do, and they rarely lose elections once in power:

Most educated elites dislike dictators, and many assume that in democracies, being pro-dictator is a fringe minority view. But in most countries, a large minority or even a majority of voters see dictatorship ("a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections") as a good form of government. This makes it possible for many authoritarians to win democratically, especially if they are seen as "the lesser of two evils". Here is a map I made of public opinion on dictatorship, based on World Values Survey data:

National Exceptionalism

I think many people acknowledge this overall trend, but since most of the newest fascist regimes have been small or poor, they still believe some countries are relatively safe. In essence, "fascism might happen in X, Y and Z, but that doesn't mean it will happen here; here is totally different than those other places. We're a true democracy, a solid democracy, and we don't wear those funny hats like the Xs and Ys do." However, most democracies now have large, extreme, and growing far-right movements, even those that were considered "immune" to fascism in the past. It used to be that all politics was local, but now that the Internet is widespread, political movements and messages can easily cross borders and be heard anywhere, globalizing trends. Educational polarization, the tendency for working-class voters to move en masse into right-wing nationalist parties while educated voters move left, is a common shift that has happened everywhere from Sweden to Brazil.

France, for example, is a very old, well-established and liberal democracy. It has had a far-right party (National Front/National Rally) since the 1970s, but voters of other parties came together in a "republican front", to keep them out of power and fight their extremism. However, this has broken down recently, with the far right becoming a large, growing, and mainstream party:

(data from here and here)

Laws might try to ban or limit fascist movements; but ultimately, any law or constitution is simply words on paper, institutions are made out of people, and guarantees of democracy mean nothing unless everyone with power believes in them. After WWII, for example, the new Italian constitution banned fascism and fascist parties. However, the old fascist party was quickly re-constituted as the "Italian Social Movement", under Giorgio Almirante, previously an official in Mussolini's government. Their successors, the Brothers of Italy, are now the largest party in Italy's legislature, under far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni:

Likewise, the banned far-right Vlaams Blok in Belgium was quickly reconstituted as "Vlaams Belang". In Germany, the post-war government and constitution tried to create a "defensive democracy" that would resist fascism, and until recently, there was no large far-right party in parliament. However, the far-right AfD has now hit a record high in polls, making them the second-largest party in Germany, even though AfD is under surveillance as a right-wing extremist movement and a regional leader was just arrested for using Nazi slogans. For now, AfD is under a "cordon sanitaire", and cannot enter government because all other parties refuse cooperation with them; but such cordons have historically broken down as the far-right gets more vote share, as recently happened with eg. the far-right Sweden Democrats (more details here):

Even countries that, for a long time, were known for being "immune" to fascism have quickly changed course. This 2017 article, for example, discusses the reasons why Spain didn't have large far-right parties, but Vox emerged as an electoral force a year later, and it is likely to be part of the government after July's elections. Likewise, Portugal was thought to be "immune", but the far-right party Chega now polls at a record high. Chile was, for a long time, known for its stability and moderate politics, but in 2021 44% of voters supported fascist Jose Antonio Kast, the son of a Nazi emigre family that held power under Pinochet. All countries have differences, and each one will have a unique story, whether it's Gyurcsany's speech in Hungary or a mysterious plane crash in Poland. However, it's now clear that this is a global trend which affects everyone everywhere, and that national quirks won't keep fascists at the door.

Only In America

In the United States, Donald Trump's efforts to overthrow democracy have been very well-documented, so I won't belabor them. As many point out, it is true that Trump failed, and that many of the dire predictions for his first term didn't come to pass. But what is less well-known is that:

Hence, it is fairly likely that Republicans will regain power in 2024, and very likely that they will sometime over the next decade, with much worse consequences than in 2001 or 2017.

America's political problems are sometimes described as "polarization", between one group of right-wing Trump supporters and another group of "woke" progressives. I'm not really a fan of "woke" ideas, but in democracies, they are made much less dangerous by being a movement run by small numbers of highly educated elites, who may influence various institutions but lack a solid electoral base. This is easier to see in Europe's multi-party systems, where the furthest-right parties (the dark blues and some gray) far outnumber the furthest-left parties (the darker red) in EU elections:

In the US, with just two parties, we have to make more guesses. However, the polling numbers we do have show that 24% of Americans would vote for Trumpist nationalism in a multi-party system, vs. only 8% who would vote for a "woke", left-wing AOC party. American conservatives far outnumber liberals, and "woke" policies like defunding the police and affirmative action are very unpopular even in left-wing areas, with the latter being defeated by huge margins in deep-blue California. Hence, even though there are both left-wing and right-wing radicals, it is vastly easier to imagine fascist dictatorship than a "woke" dictatorship, especially as the latter movement now seems to be in decline.

"Moderate" Fascism

In the West, the archetypal new dictator with a radical ideology is Hitler (with some also thinking of Stalin and Mao), so people often use those figures in historical analogies. Hitler, Stalin, and Mao were all unusually terrible even by radical dictator standards; it's worth remembering that most fascists aren't Hitler, don't want to gas the Jews, and aren't interested in starting catastrophic world wars. However, you can be an 'ordinary' dictator who is less bad than Hitler, and still be very very bad. Eg., here is some of what happened under Spain's Francisco Franco:

Chile's Pinochet was very bad:

More recently, Erdogan's Turkey has been very bad:

Other examples abound. Hence, simply "not being Hitler" does not imply that a dictatorship will be mild, or that most things will simply be "business as usual". Even if a regime is initially less extreme, many dictators will escalate their repression over time, as they solidify their power and remove liberals from high-ranking positions. This includes (eg.) communist China, which has always been authoritarian, but which has transitioned from "reform and opening up" to an intensely nationalist regime with heavy-handed repression, arbitrary seizure of businesses, and a genocide in Xinjiang.

What About AI?

After the release of GPT-4, some will see AI risk as both more dire (involving total human extinction) and more imminent than fascism risk. Honestly, that's very reasonable. However, even in a world with shorter timelines, I think fascism is still a relevant consideration:

Prediction Market

(ADDED) Since posting this, Chris Billington has created a Manifold prediction market on how likely this is. I agree with this as a statement of my views, and have bet "yes".