Why you should eat meat - even if you hate factory farming

36Drake Thomas

8jvican

8romeostevensit

28Lukas Finnveden

18Richard_Kennaway

11habryka

6kave

2Richard_Kennaway

7Richard Korzekwa

3Al V

2Linch

1Slimepriestess

1Cody Rushing

4Richard_Kennaway

4Lukas Finnveden

2Erich_Grunewald

3Cody Rushing

1jvican

23Natália

17Elizabeth

8Natália

19Shankar Sivarajan

18Auspicious

17Adam Karvonen

13Dom Polsinelli

19KatWoods

4Slimepriestess

12dr_s

12Maxime Riché

5KatWoods

3henryaj

12samuelshadrach

11brambleboy

10Richard Korzekwa

14gjm

6KatWoods

8Vaniver

7Jack_S

7Lucas Spailier

6Slimepriestess

6avturchin

8Vaniver

2avturchin

4Sherrinford

5dr_s

2Sherrinford

5dr_s

4Sherrinford

4AnnaJo

1nowl

4crypticpseudonym

3nowl

3Sherrinford

6yams

2nowl

0d_el_ez

0Foyle

New Comment

You can also look for welfare certifications on products you buy - Animal Welfare Institute has a nice guide to which labels actually mean things. (Don't settle for random good-sounding words on the package - some of them are basically meaningless or only provide very very weak guarantees!)

Personally, I feel comfortable buying meat that is certified GAP 4 or higher, and will sometimes buy GAP 3 or Certified Humane in a pinch. Products certified to this level are fairly uncommon but not super hard to find - you can order them from meat delivery services like Butcher Box, and many Whole Foods sell (a subset of) meat at GAP 4, especially beef and lamb (I've only ever seen GAP 3 or lower chicken and pork at my local Whole Foods though). You can use Find Humane to search for products in your area.

I've been doing this all my life. In the US, I buy Grass-Fed Pasture Raised Eggs by Coastal Hill (available in Good Eggs, Gus, and other grocery stores in the US) and Alexandre Farms milk and dairy products.

However, I wish it was this simple. Just recently, I learned that Alexandre Family Farms has been accused of serious animal welfare violations. Please skip if you're sensitive to this information:

- https://archive.md/newest/https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/04/alexandre-farms-treatment-of-animals/677980/

- https://www.peta.org/news/alexandre-family-farm/

- https://www.farmforward.com/news/usda-confirms-animal-abuse-and-cruelty-at-alexandre-family-farm-dairy-now-admits-wrongdoing-legal-case-moves-forward/

(There are more links, but those were the most handy in my bookmarks list.)

This is relevant because Alexandre Family Farms is, to date, one of the largest most humane organic farms in California and even the US. Their milk is one of the tastiest and most European-like. I was both sad and annoyed when I learned this.

All of that goes to say, don't blindly trust these certifications. It's likely on average they increase animal welfare, but it's still plenty far ahead of suffering-free "humane" conditions.

Specifically: humanely raised often indicates only that they were fed vegetarian feed. This made me so angry when I read the fine print and I think everyone involved should be sued into oblivion.

I thought a potential issue with wild caught fish is that other consumers would simply substitute away from wild to farmed fish, since most people don’t care much and wild caught fish supply isn’t very elastic.

But anchovies and sardines (as suggested in the post) seem like they avoid that issue since apparently there’s basically no farming of them.

I also think it’s just super reasonable to eat animal products and offset with donations — which can easily net reduce animal suffering given how good donation opportunities there are.

I also think it’s just super reasonable to eat animal products and offset with donations

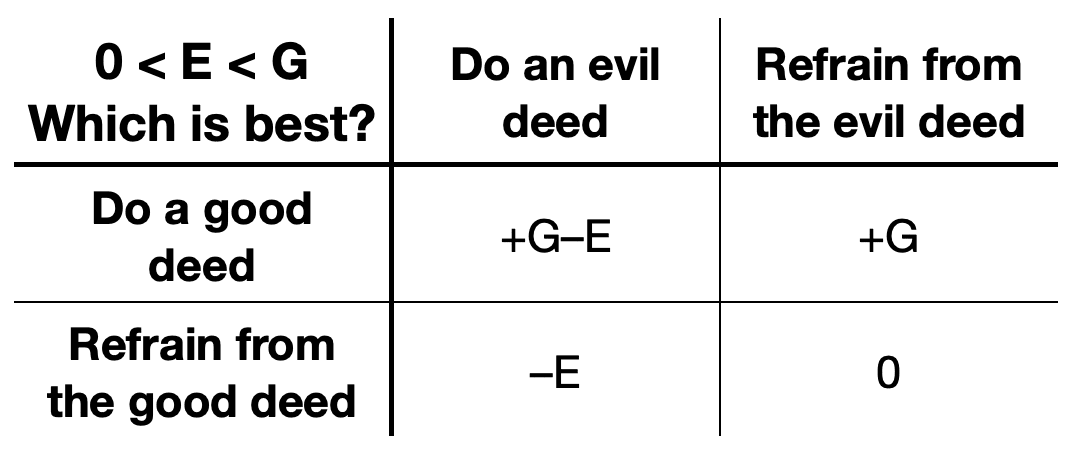

The concept of offsetting evil with good does not make sense. Even if the good outweighs the evil, it would be even better to not do the evil thing, and still do the good thing.

In situations where a single act has both good and evil consequences, such as the classic trolley problem, it may make sense to calculate the net amount of good. It does not make sense when the good and the evil come from separate actions that can be chosen independently of each other.

I imagine there could be an argument along the lines of something something timeless decision theory, to exclude the choice of doing good and not evil, but I do not see what it could be.

ETA: I see there have been a few (ETA2: a lot of) disagreement votes. I can't say much to those without any comments to go on, but here's a diagram that expresses things as starkly as possible. You can choose any of the four boxes. Which one?

Everything has a cost. Inconvenience, taste, enjoyment, economic impacts. The argument that for some reason in the domain of animal welfare we should stop doing triage and just do everything has been discussed a lot, and responded to a lot.

See also Self-Integrity and the Drowning Child.

I thought Richard was saying "why would the [thing you do to offset] become worth it once you've done [thing you want to offset]? Probably it's worth doing or not, and probably [thing you want to offset] is bad to do or fine, irrespective of choosing the other"

Indeed. There is no linkage between the two actions in the example before us. Offsetting makes no sense in terms of utility maximisation.

Where, then, does its appeal lie? Here are two defences of offsetting which I have not seen presented, although I expect that the second one may be familiar to followers of religions that practice the rite of confession. Common to both is the idea that offsetting is done first of all for oneself, only secondarily for the world.

-

The principle of offsetting one's sins (eating meat, not recycling, flying, existing) can be understood as a practice that simplifies the accounting. For every evil thing that one does, make sure to also do a greater good. One's account is then sure to always grow, never shrink. This avoids any complex totting up of sin and virtue over longer periods. This is not about maximizing goodness, but establishing a baseline that at least ensures that one will not backslide ever deeper into sin. From such a foundation, one may then build a life of greater virtue.

-

The discipline of offsetting is good for the soul. The good act undertaken in the wake of an evil one is performed not merely because it is good, but as a penance for the evil, a reminder that one has fallen short. It keeps the evil act before one's mind, to assist one to do better in future. For a prerequisite for all virtue is noticing what you are about to do and choosing, instead of noticing what you have done, when it is beyond choice.

Each of these has its own failure mode.

-

Offsetting to compensate for evil can become offsetting to justify evil, as if saving two lives were to give one a licence to end one.

-

Offsetting as penance can result in penances that accomplish no good, such as saying long series of prayers or self-flagellation.

One way of thinking about offsetting is using it to price in the negative effects of the thing you want to do. Personally, I find it confusing to navigate tradeoffs between dollars, animal welfare, uncertain health costs, cravings for foods I can't eat, and fewer options when getting food. The convenient thing about offsets is I can reduce the decision to "Is the burger worth $x to me?", where $x = price of burger + price of offset.

A common response to this is "Well, if you thought it was worth it to pay $y to eliminate t hours of cow suffering, then you should just do that anyway, regardless of whether you buy the burger". I think that's a good point, but I don't feel like it helps me navigate the confusing-to-me tradeoff between like five different not-intuitively-commensurable considerations.

The most probable intuition behind the disagreements, it appears to me, is that "a person going around doing a bunch of good things and a little bit of bad-evil things is net-positive and we should keep him around even if we can't fix him, and a different person doing the same amount of evil things but not 'offsetting' them with anything is a bigger problem."

I agree if you model people as along some Pareto frontier of perfectly selfish to perfectly (direct) utilitarian, then in no point on that frontier does offsetting ever make sense. However, I think most people have, and endorse, having other moral goals.

For example, a lot of the intuition for offsetting may come from believing you want to be the type of person who internalizes the (large, predictably negative) externalities of your actions, so offsetting comes from your consumption rather than altruism budget.

Though again, I agree that perfect utilitarians, or people aspiring to be perfect utilitarians, should not offset. And this generalizes also to people whose idealized behavior is best described as a linear combination of perfectly utilitarian and perfectly selfish.

Responding to your confusion about disagreement votes: I think your model isn't correctly describing how people are modelling this situation. People may believe that they can do more good from [choosing to eat meat + offsetting with donations] vs [not eating meat + offsetting with donations] because of the benefits described in the post. So you are failing to include a +I (or -I) term that factors in peoples abilities to do good (or maybe even the terminal effects of eating meat on themself).

The good flowing directly from the evil (here the positive effect on one’s own health) just lowers the value of E. So long as it remains positive, top right is still the highest value. If the benefit is enough to make E negative (i.e. net good), then top left becomes the highest. But then the good action is not offsetting the evil. The “evil” action has already offset itself. The only thing to recommend the (other) good action is that it is good, independently of the evil.

The only sensible scenario I can come up with is if better sustenance enables one to work harder, earn more, and donate more. But that is not offsetting an unavoidable sin with a good deed, it is committing the sin to be able to do the good deed. Eating meat to give, one might call it.

I'm somewhat sympathetic to this reasoning. But I think it proves too much.

For example: If you're very hungry and walk past someone's fruit tree, I think there's a reasonable ethical case that it's ok to take some fruit if you leave them some payment, if you're justified in believing that they'd strongly prefer the payment to having the fruit. Even in cases where you shouldn't have taken the fruit absent being able to repay them, and where you shouldn't have paid them absent being able to take the fruit.

I think the reason for this is related to how it's nice to have norms along the lines of "don't leave people on-net worse-off" (and that such norms are way easier to enforce than e.g. "behave like an optimal utilitarian, harming people when optimal and benefitting people when optimal"). And then lots of people also have some internalized ethical intuitions or ethics-adjacent desires that work along similar lines.

And in the animal welfare case, instead of trying to avoid leaving a specific person worse-off, it's about making a class of beings on-net better-off, or making a "cause area" on-net better-off. I have some ethical intuitions (or at least ethics-adjacent desires) along these lines and think it's reasonable to indulge them.

For example: If you're very hungry and walk past someone's fruit tree, I think there's a reasonable ethical case that it's ok to take some fruit if you leave them some payment, if you're justified in believing that they'd strongly prefer the payment to having the fruit. Even in cases where you shouldn't have taken the fruit absent being able to repay them, and where you shouldn't have paid them absent being able to take the fruit. ... And in the animal welfare case, instead of trying to avoid leaving a specific person worse-off, it's about making a class of beings on-net better-off, or making a "cause area" on-net better-off.

I think this is importantly different because here you are (very mildly) benefitting and harming the same person, not some more or less arbitrary class of people. So what you are doing is (coercively) trading with them. That is not the case if you harm an animal and then offset by helping some other animal.

In your fruit example, the tree owner is coerced into trading with you, but they have recourse after that. They can observe the payment, evaluate whether they prefer it to the fruit, and adjust future behaviour accordingly. That game theoretic process could converge on mutually beneficial arrangements. In the class of beings, or cause area, example, the individual that is harmed/killed doesn't have any recourse like that. And for the individual who benefits from the trade, it is game-theoretically optimal to just keep on trading, since they are not the one who is being harmed.

(Actually, this makes me thing offsetting has things in common with coercive redistribution, where you are non-consensually harming some individuals to benefit other individuals. I guess you could argue all redistribution is in fact coercive, but you could also argue some distribution, when done by someone with legitimately derived political authority, is non-coercive.)

On the other hand, animals can't act strategically at all, so there are even more differences. But human observers can act strategically, and could approve/disapprove of your actions, so maybe it matters more whether other humans can observe and verify your offsetting in this case, and respond strategically, than whether the affected individual can respond strategically.

Oh I think I see what you are arguing (that you should only care about whether or not eating meat is net good or net bad, theres no reason to factor in this other action of the donation offset)

Specifically then the two complaints may be:

- You specify that $0 < E$ in your graph, where you are using E represent -1 * amount of badness. While in reality people are modelling $E$ as negative (where eating meat is instead being net good for the world)

- People might instead think that doing E is 'net evil' but also desirable for them for another reason unrelated to that (maybe for some reason like 'i also enjoy eating meat'). So here, if they only want to take net good actions while also eating meat, then they would offset it with donations. The story you outlined above arguing that 'The concept of offsetting evil with good does not make sense' misses that people might be willing to make such a tradeoff

I think I agree with what you are saying, and might be missing other reasons people are disagree voting

Often these sardines and anchovies, being so small, are the catch byproduct of many larger fishes (like tuna).

For example, famously Adventists are vegetarians and live longer than the average population. However, vegetarian is importantly different from vegan. Also, Adventists don’t drink or smoke either, which might explain the difference.

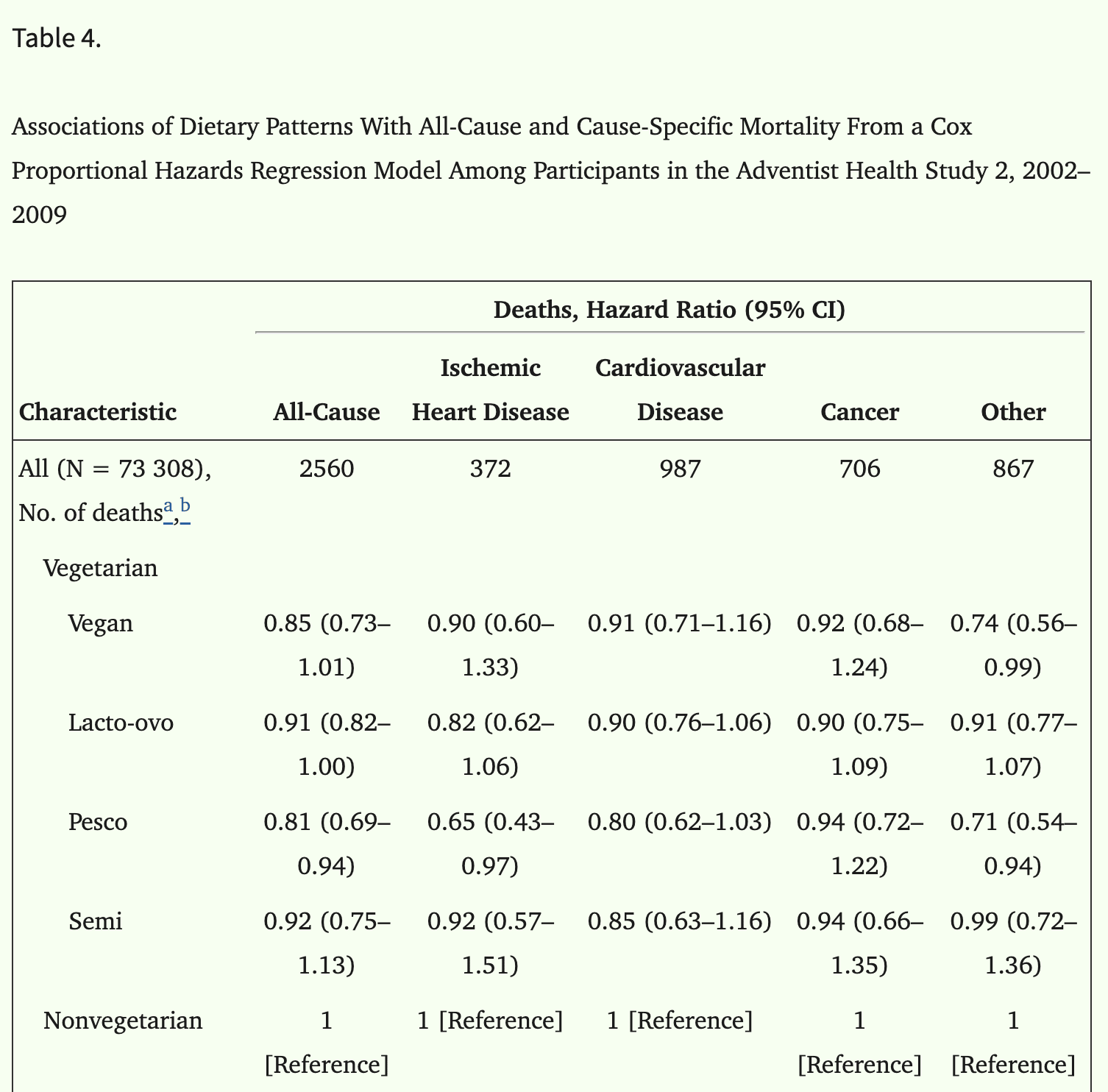

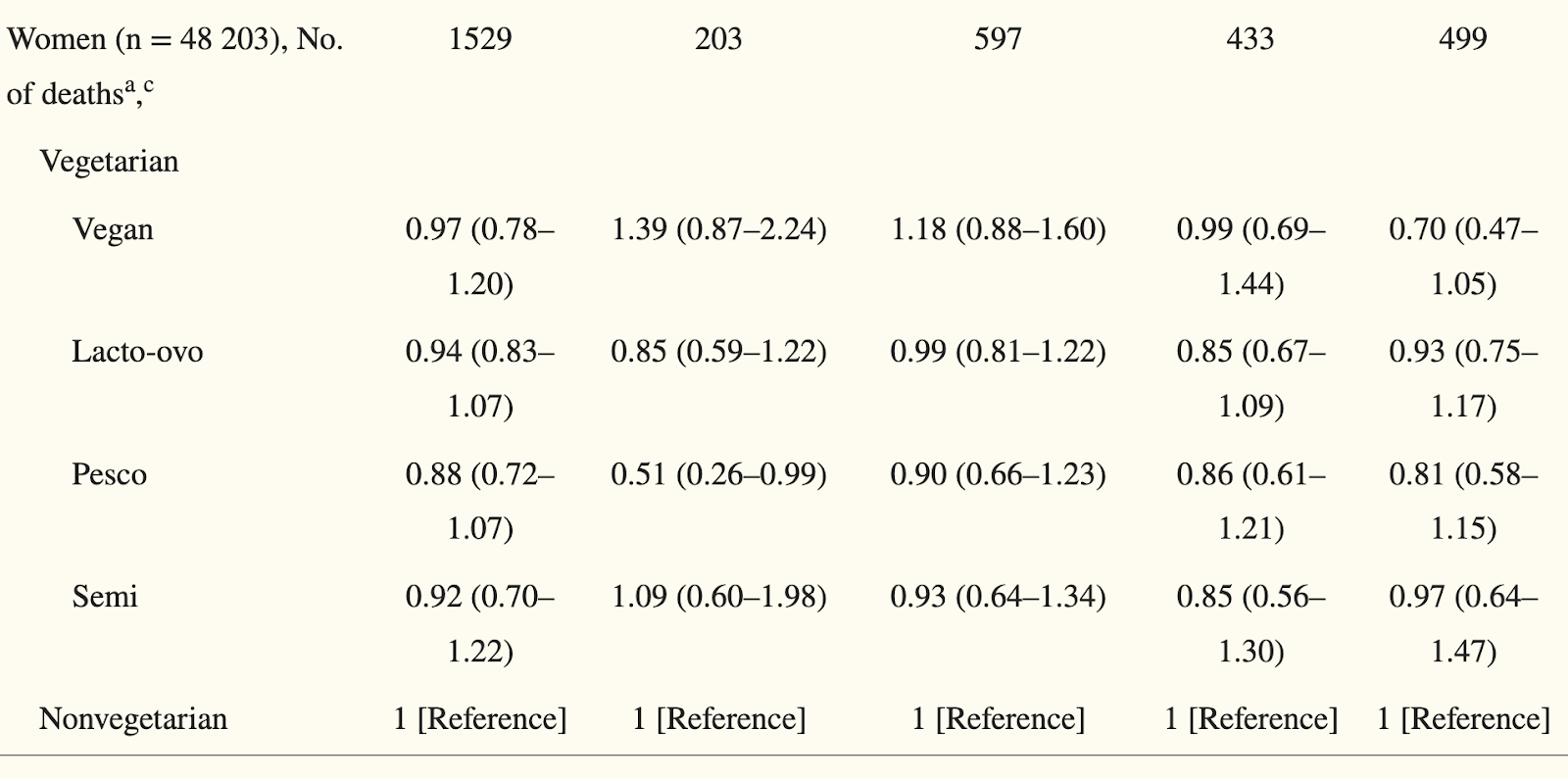

Nit: we actually do have a study that looks at the mortality rate of vegan Adventists in particular. They fare well, having a nearly significantly lower mortality rate than omnivores after adjustments for drinking, smoking and other things:

As you can see, groups that restrict meat intake in some form all trend towards having a lower mortality rate than the "nonvegetarian" group. The pescatarian mortality rate appears slightly lower than the vegan one, but in practice the difference is too small and the confidence intervals are too wide to tease out which one is actually lower. When broken down by sex, nearly all of the effect is concentrated in men, while all diets are pretty similar to each other in women.

Make of that what you will; I am not claiming there's a causal effect, though note that the study does control for a lot of confounders, such as smoking, drinking, age, race, income, education, marital status, etc.

Meat consumption is a predictor of longer life expectancy. This relationship remained significant when influences of caloric intake, urbanization, obesity, education and carbohydrate crops were statistically controlled.

You will get different results when examining this question worldwide (as in this study) vs in a developed country. Worldwide, meat is expensive, especially red meat, and so its consumption correlates with wealth. There have been several observational studies examining the relationship between vegetarianism and mortality or chronic diseases, you can find a non-cherrypicked list of systematic reviews here. Most find favorable outcomes for vegetarians. Though again, make of that what you will, I am not claiming it's causal. In developed countries, of course, vegetarianism likely correlates with conscientiousness, which affects health in other ways. But these studies arguably should be mentioned in any overview of the health effects of vegetarianism that aims to be representative and balanced.

Beef, especially pasture-raised (different from grass-fed). Factory farming of cows is far less bad than other animals. They often have access to the outdoors for a large percentage of their lives. They are cuter so we treat them better. Also, since they’re massive, even if their lives are quite bad, if you ate exclusively cow for a year, you most likely wouldn’t finish a single cow. Compare that to a chicken, which might last you a day. The same logic applies to dairy.

I think there should be a bit more research on this; it's not obvious to everyone that eating beef causes less suffering than eating chicken, or if it's actually the other way around. This depends a lot on your moral intuitions, so the answer won't be the same for everyone. From what I've seen, EAs tend to ascribe more moral worth to smaller animals than most other people would, leading to the conclusion that eating larger animals causes less suffering.

However, my impression is that ~everyone who's looked into it typically does agree that consuming dairy, bivalves, and non-farmable[1] species of fish like sardines causes very little suffering, with bivalves often being considered vegan.

- ^

See this comment for the relevant difference between wild-caught and non-farmable species of fish

Your own screenshot shows that pescatarians do better than vegans (not statistically significant, but neither is the difference between vegans and omnivores). And if you break it down by sex (and continue to ignore statistical significance), veganism is the worst choice for women after unconstrained omnivorism

More of my opinion of this study here.

Your own screenshot shows that pescatarians do better than vegans (not statistically significant, but neither is the difference between vegans and omnivores). And if you break it down by sex (and continue to ignore statistical significance), veganism is the worst choice for women after unconstrained omnivorism

I addressed both of those points in my comment above. From my comment:

The pescatarian mortality rate appears slightly lower than the vegan one, but in practice the difference is too small and the confidence intervals are too wide to tease out which one is actually lower. When broken down by sex, nearly all of the effect is concentrated in men, while all diets are pretty similar to each other in women.

To explain this more in-depth, you cannot conclude from this table that "veganism is the worst choice for women after unconstrained omnivorism." The confidence intervals of the adjusted hazard ratios for the "vegetarian" diets for women are essentially identical. It's not just about failing to meet an arbitrary threshold of statistical significance - the difference between those diets has a very high p-value, not a p-value that almost approaches significance but falls just short of it.

Meanwhile, the adjusted hazard ratio of veganism is significant in men, compared to omnivorism. Quoting from my old comment:

The 95% confidence intervals of the adjusted hazard ratios for overall mortality, for men, were [0.56, 0.92] and [0.57, 0.93] for vegan and pescatarian diets, respectively, and for women the CIs are [0.72, 1.07] and [0.78, 1.20], respectively. For women, the confidence intervals for all diets are [0.78, 1.2], [0.83, 1.07], [0.72, 1.07] and [0.7, 1.22].

What these CIs indicate is that there was likely no difference between pescatarian and vegan diets for men, both of which are better than omnivorism, and likely no difference between any of the diets for women.

The CIs for women specifically look so similar that you could pretend that all of those CIs came from different studies examining the exact same diet, and write a meta-analysis with them, and readers of the meta-analysis would think, “oh, cool, there's no heterogeneity among the studies!”

In fact, we can go ahead and run a meta-analysis of those aHRs (the ones for women), pretending they're all for the same diet, and quantitatively check the heterogeneity we get. Doing so, with a random-effects meta-analysis, we find that the is exactly 0%, as is the . The p-value for heterogeneity is 0.92. Whereas this study should update us a little bit on pescatarian diets being better than vegan diets for women, these differences are almost certainly due to chance. No one would suspect that these are actually different diets if you had a meta-analysis with those numbers.

Since the total meta-analytic aHR is also very close to 1, it also looks like none of the diets are meaningfully associated with increased or decreased mortality for women, though there was a slight trend towards lower mortality compared to the nonvegetarian reference diet (p-value: 0.11).

I appreciate this post for the "How to reduce suffering of the non-human animals you eat" section - as someone who empathizes with the vegan cause but just can't stop eating animal products (due to both weak will and health concerns) it's highly appreciated.

In Minnesota many people I know buy their beef from local farmers, where they can view the cows when buying the meat at the farm. From what I've heard the cows appear to be healthy and happy, and the prices are typically cheaper than the grocery store if buying in bulk.

I wish that we could be optimally healthy without eating animals. Honestly, I’d prefer not to eat plants either, because I put a disconcertingly high probability that plants are also sentient.

This is clearly not the main point of this post but I am curious why you believe this as it seems to be an extremely fringe opinion in a way animal suffering is not. Shrimp welfare has a lot of backlash and at least shrimp have neurons and whatnot. Also, do you have any thoughts on mushrooms?

Quick response dashed off without sources:

- Trees actually have a cluster of cells at the base of their root system that seems to act in very brain like ways. If you damage it or cut it off, suddenly the tree starts acting "dumbly", like it's brain damaged.

- Trees actually do a ton of really complex things that certainly look like they're communicating with other trees and plants, via signals sent along their root systems (I vaguely recall it was electrochemical signalling, much like in brains?). They stop doing such things when they get "brain damage" to their root cluster that seems to do signal coordination.

- If you watch videos of vines growing but sped up, they look very much like worms, tapping around, "looking" for where they should grow. And they have a little cluster of cells at their tip that act as sensors. If you cut the sensor tip off, they stop "looking" and look like a drunk man, stumbling around blindly. It's like you cut off their eyes.

- Plants are actually able to sense a ton of different things, and they have reactions to them. It's just that we can't see the reactions because they either a) happen on too slowly for us to see them or b) happen chemically, so we can't see them. For example, you know the famous study showing that when a giraffe eats a particular type of tree leaves, the tree releases a chemical that goes through the air and "warns" other trees in the area, and they start developing tannins which make their leaves bitter tasting to the giraffe? I thought that was a neat one-off trick. It's actually super duper common across plants. We're just starting to scratch the surface of all of the things they're doing we can't see with our normal senses.

- They've done some really clever experiments to show that some plants at least, can learn and remember things.

Again, I don't put crazy high odds. I'd probably put the odds that an oak tree is conscious at about the same probability I put on a worm being conscious.

I recommend reading The Hidden Life of Trees for an infodump about all of the crazy things trees do if you're curious about this sort of thing.

my intuition is that trees and plants aren't conscious in the same way we are but they are agents and they still have things like desires, goals, etc. I generally place moral value in agency itself not just consciousness or sentience, and that lets me get around what would otherwise feel like substrate-chauvinism.

Vegans/vegetarians had over twice the odds of depression (OR ~2.14) compared to omnivores

I would be a bit leery about selection effects here too. What kind of person becomes vegan? One who is generally very aware about suffering or social problems, or possibly very neurotic about what they eat. Sometimes both. If you're the kind who stops eating meat because they feel that farming and killing animals is monstrous, and then still have to live in a world which keeps perpetuating that, not to mention however many other things you also feel are similarly monstrous, aren't you going to be more prone to depression than the average person who may not worry much about any of that?

Do you think cow milk and cheese should be included in a low-suffering healthy diet (e.g., should be added in the recommendations at the start of your post)?

Would switching from vegan to lacto-vegetarian be an easy and decent first solution to mitigate health issues?

I live in India and I’m vegetarian. This is very easy to do because a lot of Hindus are also vegetarian for religious animal welfare reasons. I consume milk and milk products but not egg. I have been low on B12 but not to the point it’s a health hazard and I have supplemented it in past.

I think it’s possible in theory to ethically milk cows, but yes situations in practice differ.

There was that RCT showing that creatine supplementation boosted the IQs of only vegetarians.

While looking for the RCT you're referencing, I instead found this one from 2023 which claims to be the largest to date and which states "Vegetarians did not benefit more from creatine than omnivores." (They tested 123 people altogether over 6 weeks; these RCTs tend to be small.)

A systematic review from 2024 states:

To summarize, we can say that the evidence from research into the effects of creatine supplementation on brain creatine content of vegetarians and omnivores suggests that vegetarianism does not affect brain creatine content very much, if at all, when compared to omnivores. However, there seems to be little doubt that vegans do not intake sufficient (if any) exogenous creatine to ensure the levels necessary for maintaining optimal cognitive output.

Not to mention that of all of the hunter gatherer tribes ever studied, there has never been a single vegetarian group discovered. Not. A. Single. One.

Of the ~200 studied, ~75% of them got over 50% of their calories from animals. Only 15% of them got over 50% of their calories from non-animal sources.

Do you have a source for this? I'm asking more out of curiosity than doubt, but in general, I think it would be cool to have more links for some of the claims. And thanks for all of the links that are already there!

Wait, there's something very strange about those two claims. 75% got more than half their calories from animals. 15% got more than half their calories from not-animals. So what did the other 10% do? (Exactly 50% from each, obviously :-).)

If you have the ability, have your own hens. It’s a really rewarding experience and then you can know for sure that the hens are happy and treated well.

Unfortunately, I'm moderately uncertain about this. I think chickens have been put under pretty tremendous selection pressure and their internal experiences might be quite bad, even if their external situations seem fine to us. I'm less worried about this if you pick a heritage breed (which will almost definitely have worse egg production), which you might want to do anyway for decorative reasons.

Similarly, consider ducks (duck eggs are a bit harder to come by than chicken eggs, but Berkeley Bowl stocks them and many duck farms deliver eggs--they're generally eaten by people with allergies to chicken eggs) or ostriches (by similar logic to cows--but given that they lay giant eggs instead of lots of eggs, it's a much less convenient form factor).

The use of the Chinese study about healthy aging for elderly Chinese people is egregiously misleading. The OP uses it to make three separate points, about cognitive impairment, dose-response effects and lower overall odds of healthy aging. But it's pretty clear that the study is basically showing the effects of poverty on health in old age!

Elderly Chinese people are mostly vegetarian or vegan because a) they can't afford meat, or b) have stopped eating meat because they struggle with other health issues, both of which would massively bias the outcomes! So their poor outcomes might be partly through diet-related effects, like nutrient/protein deficiency, but could also be sanitation, malnutrition in earlier life (these are people brought up in extreme famines), education (particularly for the cognitive impairment test), and the health issues that cause them to reduce meat. The study fails to control for extreme poverty by grouping together everyone who earned <8000 Yuan a year (80% of the survey sample!), which is pretty ridiculous, because the original dataset should have continuous data.

But, the paper does control for diet quality, and it also makes it abundantly clear that diet quality is the real driver, and that healthy plant-based diets score similarly to omnivorous diets! "With vegetarians of higher diet quality not significantly differing in terms of overall healthy aging and individual outcomes when compared to omnivores".

Probably less importantly, it conditions on survival to 80, which creates a case of survivorship bias/collider bias. So there could be a story where less healthy omnivores tend to die earlier, and the survivors appear healthier.

I'm surprised, in discussions related to veganism, to never see mentioned the point that having the people who care the most about animal suffering not buy meat at all shift economic incentives for producers in a bad way. I'm not involved in vegan culture, so maybe these discussions do happen and I'm just not aware, but it never popped up anywhere I saw it.

If the only people who care about animals do not buy meat at all, then factory farmers have no incentive whatsoever in producing ethical meat. In theory, we could imagine that the ethical-eaters would only add a few ethical-producers on top of all the usual horrible factory farming. In practice, everything is more interconnected than that, and I expect a large market for very ethical meat to also shift a significant portion of the unethical meat market in at least a moderately-ethical meat direction.

Asking Claude gives me the same three counter arguments that I thought most likely a priori :

- There are already some would be ethical eaters, so this already happen in practice - and I suppose vegans do not think the addition of their own ethical consumption would shift incentives in a significant way.

- Vegans prefer a revolution, based on plant-based alternatives or lab-grown meat, not a gradual improvement in farming conditions, and they think incentivizing these alternatives has more of an impact than incentivizing more ethical animal-based production.

- Some people simply do not want to cause animal suffering, out of their own personal feelings on the matter rather than out of more 'logical' moral reasoning.

All of these are relevant and probably true, but I note that they are more anti-anti-vegan arguments than pro-vegan arguments. They don't suggest any moral imperative to be vegan rather than an ethical eaters.

Well, you've managed to write a post that is both very interesting and also makes me deeply uncomfortable so kudos there.

Honestly, I’d prefer not to eat plants either, because I put a disconcertingly high probability that plants are also sentient.

Deeply relatable, I can't wait to be genemodded to be able to photosynthesize.

I've been vegan for about three and a half years now after about three and a half years of omnivory after roughly 10 years of vegetarianism.

When I first went vegan it felt like a really profound moment of waking up and paying attention to the world and fully living within my values for the first time. I kinda did suspect it would harm me and I just didn't care at all, I cared about the the outcomes for the world. I took going vegan slowly and replaced things in my diet one at a time, making sure I was doing it as sustainably as possible and maintaining my health and nutrient balance as best I could.

I like to think that I'm pretty good at noticing my body's needs and adjusting my diet to meet them, I increased the amount of impossible products I ate when I started craving iron, I increased the amount of protein and vegetables I ate when started getting sore or moody, and overall that feedback loop has at least felt like it's working, my body doesn't feel bad and I don't feel like I'm missing any vital nutrients, but the mental health effects could easily have been subtle enough to miss.

Which is where your post begins to get extremely uncomfortable to me, because...well if I actually look back over the years, those three years I spent being an omnivore did seem to correlate with increased productivity, emotional affect, and outlook on life, and in the three years I've spent vegan my productivity has dipped somewhat, my affect has gotten more neurotic, and while I wouldn't say I'm anywhere near depressed, i don't really feel as happy overall as I did back then. However...let's look at confounders.

The biggest confounder is that my omnivore period corresponded with essentially backing entirely out of the EA/rationalist scene and focusing on my personal life, my art, and my own development and growth. I wasn't as paranoid about global risks and I disengaged from most politics. I felt at least somewhat bad about not at least continuing to be vegetarian though and so during that period I also went around saying I was ontologically evil and no act against me was wrong. I don't know how much of my mental health stuff is related to issues with my life not being particularly stable or optimised for my flourishing, how much of it is entangled with taking catastrophic risk seriously and letting that inform my choices, and how much of it is dietary, it's all kinda smeared together into general life arcs. At least some of that seems likely to be responsible for my emotional affect and level of productivity, it's hard to be productive when you're constantly having to put out fires and juggle minor disasters to stay housed and fed.

When I went vegan, that corresponded with my learning decision theory, studying formal logic, re-engaging with the rationalist scene, and shifting my life plans to focus on mitigating and reducing x-risks, which is certainly stressful enough on its own without even factoring in the precarity in my personal life. That said, it's felt much more sustainable this time around and I don't feel at risk of crashing out the way that it seemed a lot of people did in the 2019-2021 period. I learned to put on my oxygen mask first and I think I'm doing a pretty good job presently of approaching things in way that won't drive me off a cliff into severe mental illness.

I do worry about impairing my cognition or pushing myself into a worse state of mind from nutrient imbalances though, I want to be in things for the long-haul, saving the world is a marathon not a sprint, and it does no one any good if I ruin my health and can't keep doing useful work. I try to listen to my body and keep healthy, my bloodwork looks frankly great every time I get blood drawn and my doctor says I'm very healthy for my age. It does still worry me though. Maybe on a deep level I know I'm doing something unhealthy, because your post was very hard to read and disquieting, like it's pointing to something I can see but would really prefer to not see.

All that being said like...I don't think I can actually stop being vegan at this point. Veganism has gotten wrapped up in my purity/disgust reactions and the idea of eating meat is just...deeply deeply unsettling and I legitimately don't think I could force myself to do it. Even the idea of eating lab meat feels really gross and bad, and there's not even any ethical issues there. I'm...maybe not approaching this as rationally as I was when I decided to go vegan. In fact I would say I know I'm not, it's really emotionally charged and talking about veganism with omnivores frequently reduces me to tears. There's probably some sort of moral scrupulosity thing going on there where I see being vegan as the proof that I'm not a psychopathic monster and it feels hard to imagine how I could live with myself if I started eating meat again. Yeah I could try to do it in a way that minimizes suffering to some degree but that flatly doesn't feel good enough. I've said multiple times in the past that I'd be vegan until the day I died, I don't feel tempted by animal products I feel disgusted by them. I don't have any desire to "cheat", even if it would improve my health to do so. So if it is harmfully impacting my health and impeding my ability to do good work in the world, that's just...really deeply upsetting. I'm not utilitarian enough to bite that bullet and not feel like an irredeemable monster. I know asking this probably veers somewhat off topic from the actual discussion of nutrition but just...gosh what do I do?

There is a restaurant in Washington where they serve the right leg of the crab which will later regenerate.

Eating a largest possible animal means less amount of suffering per kg. Normally, the largest are cows. You can compensate such suffering by having shrimp farm with happy shrimps. Ant farm is simpler, I have one but for this reason.

Eating a largest possible animal means less amount of suffering per kg.

I think this is the right general trend but the details matter and make it probably not true. I think cow farming is probably more humane than elephant farming or whale farming would be.

Larger animals tend be more intelligent just because they have larger brains, so their sufferings will be more complex: they may understand their fate in advance. I think whales and elephants are close to this threshold.

An opposite logic may be valid: we should eat animals with smallest brains as their suffering will be less complex and also each of them is less individual and more like a copy of one another. Here we assume that suffering of two copies is less than of two different minds.

Not to mention that of all of the hunter gatherer tribes ever studied, there has never been a single vegetarian group discovered. Not. A. Single. One.

I think this does not prove as much as the "Not. A. Single. One." part seems to try to hammer home to the reader. It merely shows that people that evolve under conditions of scarcity and extremely low technology do not get a strong evolutionary benefit from excluding animals from their diet. But do vegans in general assume the opposite? Additionally, India might be a relevant case study here, because vegetarianism seems to have been common there for a long time.

I think the point is less that the tribes didn't go vegetarian because this was better for them, and more that if our species subsisted for hundreds of thousands of years on a mixed diet that included meat, odds are our metabolism adapted to that.

Additionally, India might be a relevant case study here, because vegetarianism seems to have been common there for a long time.

The thing is, that likely only happened once civilisation went agricultural, and we know agricultural diet (with a lot less meat for peasants) was a big downgrade and people became significantly more sickly as a result. So it's a useful case study but not likely to really change the point.

I agree that our metabolism is adapted to eating a mixed diet, but that mostly means that you should not blindly delete animal products from your diet. It is theoretically possible that you can replace animal products with other things, given that we live in a technologically different society. Of course you can say "we do not know what to replace on the micro level", or make Chesterton's Fence arguments, but then it is a bit unclear to what kind of diet we should "return". You can make the adapted-metabolism argument about any selective diet. Maybe we have to eat Offal because our ancestors did, or eat chicken soup because my aunt did that, because these things contain very important things we do not fully understand. Or maybe our ancestors had to eat these things because they were efficient ways to get protein and fat into their bodies, and we consume enough of that already and too much of the bad things we do not fully understand that they also contain. So the adaptation argument alone is not enough.

Well, there are attempts at "paleo diets" though for the most part they seem like unscientific fads. However it's also true that we've been at the agricultural game for long enough that we have adapted to that as well (case in point: lactose tolerance).

Or maybe our ancestors had to eat these things because they were efficient ways to get protein and fat into their bodies, and we consume enough of that already and too much of the bad things we do not fully understand that they also contain.

That doesn't convince me much, we mostly consume enough (or too much) of that via animal products in the first place. Well, putting aside seed oils, but their entire point is to be a cheap replacement for an animal saturated fat (butter) most of the time. Our diets tend to have "too much" of virtually anything, be it cholesterol from animal products or refined carbs from grains. We just eat too much. The non-adaptive part there is "we were never meant to deal with infinite food at our fingertips and so we never bothered evolving strong defences against that". Maybe a few centuries of evolution under these conditions would change that.

On the unhealthy to be vegan point:

idk about "mitochondrial dysfunction" but I can easily clock vegans by the quality of their skin (w/ false positives from malnutrition/MTHFR issues, but few-no false negatives.)

Unrelatedly, shifting demand of meat into more humane meat creates stronger economic incentives for the companies to treat their animals well

have they tested that?

they say in a reply that they think the difference they notice is caused by folate (aka vitamin B9) deficiency, but many vegans take supplements and get blood tests to avoid having any deficiencies in the main nutrients. so maybe they're only noticing vegans who don't take supplements (that contain b9).

Like you, I used to be a strict vegan, but I recently started eating a few select non-vegan foods for a variety of reasons, mostly social. I noticed that I was actually able to have a greater influence on others' diets when I showed flexibility in my own. Like you, I occasionally eat certain types of seafood and humanely-produced eggs.

However, I take issue with your argument about cows. Factory-farmed cows might be marginally better off than factory-farmed chickens or pigs, but they still suffer a great deal. In particular, factory-farmed dairy cows arguably suffer the worst of all these animals.

In order to produce milk, the cow needs to have a baby, but of course the cow doesn't get to keep her baby. Like all mammals, cows have an incredibly strong mothering instinct and will become tremendously distressed and depressed when their babies are taken away. The gut-wrenching wails of a mother cow whose baby has been taken away are well-documented. Moreover, there's surely a lot of cortisol in her milk, among other grief-related hormones you wouldn't want to consume (and that pasteurization won't eliminate).

That said, even if it were true that factory-farmed cows were treated well, they would still probably cause more suffering than all other factory-farmed animals put together when you consider the environmental impact of the methane they produce as well as the deforestation and habitat destruction that comes with feeding them. Because they're so big, they require a lot more feed than these other animals, and their methane-laden waste is a more significant culprit of climate change than CO2 from vehicles. Cutting way back on beef and dairy is probably the single most effective way of reducing one's carbon footprint.

It's also worth pointing out that the vast majority of the world's population is lactose intolerant, at least according to certain metrics. If drinking pasture-raised milk makes you feel good, then go for it, but you're probably more the exception than the rule. Most people would probably be better off consuming no dairy at all. I've gone most of my life without eating dairy and have never taken calcium supplements, and I've never been anywhere near calcium deficient, which I know because I have regular bloodwork done.

I will say that I appreciate your perspective that we haven't yet identified all the components that comprise the various foods we eat, but I also think everyone has slightly different nutritional needs, and different reactions to the foods that can provide those nutrients. I think the best we can do for now is figure out what works for each of us through trial and error, with the understanding that what worked for you may not work for me, and vice versa.

I don't know what updates to make from these studies, because:

- Idk if the negative effects they found would be prevented by supplements/blood tests.

- Idk if there were selection effects on which studies end up here. I know one could list studies for either conclusion ("eating animals is more/less healthy than not"), as is true of many topics.

What process determined the study list?

There’s the sniff test. A large percentage male vegan influencers look pale and sickly. (I’m not going to name names, but if you follow the space at all, you’ll know who I’m talking about, because it could refer to so very many of them.) Of course, you can build muscle and be fit as a vegan, but it is much harder, and we know that muscle mass is a significant predictor of all sorts of positive health outcomes.

I do not "follow the space" of male vegan influencers, so I cannot judge it. However, I would like to ask for a comment on what vegan strongman Patrik Baboumian, "face of a campaign by the animal rights organization PETA", said in an interview (Google translation):

He had long since become a figurehead of the vegetarian movement. He felt the pressure: "I was afraid of failure if I also eliminated dairy products. They were the most important source of protein for me as a vegetarian strength athlete."

But things turned out differently. As a vegan, Baboumian suddenly had to eat even less, he says, "because my metabolism became more efficient." Animal protein acidifies the metabolism because it is rich in sulfur-containing amino acids, "and when these are metabolized, a lot of acid is produced."

With plant proteins, things were different: "My acid-base balance was suddenly balanced, and that had a very positive effect. For example, all the inflammatory processes that automatically arise during strenuous exercise healed much better. So I was able to train more effectively with less protein and fewer calories."

I really don’t know how to evaluate this claim, and I mostly just want to see logs (of his lifts, intake) backing it up.

I’m also curious to know how much lactase he produces (the majority of humans are some degree of lactose intolerant, which can lead to some of the effects he described, especially at high volume of ingestion, but via a different mechanism than ‘sulfur’).

I also think ‘one guy can do it, actually’ isn’t much evidence here; there are lots of genetic freaks wandering around, including a sedentary friend of mine with a six pack who only ever consumes beer (10+ per day) and pastries.

Most people would consider sacrificing their health for others to be too demanding an ethical framework.

(This comment is local to the quote, not about the post's main arguments) Most people implicitly care about the action/inaction distinction. They think "sacrificing to help others" is good but in most cases non-obligatory. They think "proactively hurting others for own benefit" is bad, even if it'd be easier.

Killing someone for their body is a case of harming for own gain. The quote treats it as just not making a sacrifice.

I think it does feel to many that not-killing animals is proactive helping, and not-not-killing animals is inaction, because the default is to kill them (and it's abstracted away so actually one is only paying someone else to kill them and it's never presented to one as this, and so on). And that's part of why animal-eating is commonly accepted (though the core reason is usually thinking animals are not all that morally relevant).

But in the end "proactively helping others others is nonobligatory" wouldn't imply "not-killing animals is nonobligatory".

A lot of this doesn't pass the smell test.

- Most obviously - studies that say being vegan is good for you are bad studies. Studies that say being vegan is bad for you though, you acknowledge they're correlation but seem to let it speak for itself.

- I don't really like the "just look at that crappy male vegan podcaster" argument. It's invalidated by the 3 super muscly, athletic vegan friends (rock climbing, rock climbing, fencing) I can think of, anyway.

- I think you're lumping in psychiatry with nutrition. I don't agree psychiatry is stuck in a metaphorical 1800. Generally we can give you questionnaires and run blood work and figure out how your mood is doing. Is it perfect? No. Is it good enough to reject pseudoscience and follow our psychiatry science? Yes.

- To my knowledge there is no psychiatric or medical recommendation against going vegan.

- I think you're indexing strongly on the risk of a mystery nutrient that won't matter for 5 years. I think about 2 orders of unlikelihood out there -- nutrient we really don't know about it, and the effects go a bit past the window you might correlate your vegan diet change to your mood, which I take to be around 1 year of conscientiousness.

- Part of the problem with going this hard on rejecting science as too incomplete, is which intuitionistic knowledge do you privilege? Going all in against ultra processed food is more popular, and if you accidentally put a vegan back onto more processed meats, it's not really clear this is a win, against equally probably intuitionist knowledge. I'd probably cut back on microplastics in your diet I guess. And GMOs, why not.

- You're underestimating vegan as a tradition. My gut estimate is a few million over 50-75 years. It's enough to smoke test most issues you'd run into.

Where I agree with you:

- If I had spare research dollars on this question, I would explore if vegan causes neuroses chemically. It's another chore to worry about if nothing else, but so is any culture or religion with a meal practice.

- The vegan movement as a whole is in denial that we need to eat a lot of protein. It's not a huge gap but a vegan probably wants to supplement on the order of 20-40g of protein a day on top of regular meals.

For what it's worth I was vegan about 10 years and quit about 2 years ago. I have been more neurotic since then, easily.

I struggle a lot with the arguments for suffering and ethical treatment of animals. I come from a farming region.

Wild animals almost all die horribly. Freezing to death, starving, succumbing to parasites or disease with long periods of suffering and for the most part all being ripped apart by predators. By contrast the lives of factory farmed animals are incredibly gentle and easy, with almost no suffering, and their deaths are about as low in suffering as is possible to arrange. Claims that those lives are somehow better than domesticated are arbitrary romantic human values applied in a way that I don't think have much merit. Domesticated animals do not share human values.

We have been breeding domestic animals for millennia to thrive in captivity, their psychology has been dramatically changed because we have been culling off those that reacted badly to captivity for thousands of generations - aggressive or badly behaving animals would always be first for the pot. Happy and content animals that are not stressed are most productive, so that is what farming and domesticated animal psychology have been effectively selecting for - extreme unthinking docility and contentment. They are far removed from wild animals - just as dogs are not wolves.

So when we try and impose our notions of what domesticated animals want - outdoors etc, you will find in most cases you are wrong. They just want sheltered space with steady supplies of food, not caring about crowding that 1000's of generations of their domesticated ancestors have lived with quite happily. and will often not use outdoor spaces (or use them only minimally) even if they are provided. Evolution strongly favors animals that don't waste energy, so when fed sufficiently laziness is the default.

So I place very little stock in the claims of suffering for farmed animals, or that living wild is somehow better. Almost certainly the animals in question prefer the comfort of domesticated farming environments and lives.