In the comments to the OP that Eliezer’s comments about small problems versus hard problems got condensed down to ‘almost everyone working on alignment is faking it.’ I think that is not only uncharitable, it’s importantly a wrong interpretation [...]

Note that there is a quote from Eliezer using the term "fake":

And then there is, so far as I can tell, a vast desert full of work that seems to me to be mostly fake or pointless or predictable.

It could certainly be the case that Eliezer means something else by the word "fake" than the commenters mean when they use the word "fake"; it could also be that Eliezer thinks that only a tiny fraction of the work is "fake" and most is instead "pointless" or "predictable", but the commenters aren't just creating the term out of nowhere.

Right, so it didn't come completely out of nowhere, but it still seems uncharitable at best to go from 'mostly fake or pointless or predictable' where mostly is clearly modifying the collective OR statement, to 'almost everyone else is faking it.'

EDIT: Looks like there's now a comment apologizing for, among other things, exactly this change.

It also seems uncharitable to go from (A) "exaggerated one of the claims in the OP" to (B) "made up the term 'fake' as an incorrect approximation of the true claim, which was not about fakeness".

You didn't literally explicitly say (B), but when you write stuff like

The term ‘faking’ here is turning a claim of ‘approaches that are being taken mostly have epsilon probability of creating meaningful progress’ to a social claim about the good faith of those doing said research, and then interpreted as a social attack, and then therefore as an argument from authority and a status claim, as opposed to pointing out that such moves don’t win the game and we need to play to win the game.

I think most (> 80%) reasonable people would take (B) away from your description, rather than (A).

Just to be totally clear: I'm not denying that the original comment was uncharitable, I'm pushing back on your description of it.

It's not like this is the first time Eliezer has said "fake", either:

I validate this as a nonfake alignment research direction that seems important.

If he viewed almost all alignment work as nonfake, it wouldn't be worth noting in his praise of RR. I bring this up because "EY thinks most alignment work is fake" seems to me to be a non-crazy takeaway from the post, even if it's not true.

(I also think that "totally unpromising" is the normal way to express "approaches that are being taken mostly have epsilon probability of creating meaningful progress", not "fake.")

For 36 (Agent Foundations) in particular: I notice a bunch of people in the comments saying Agent Foundations isn’t/wasn’t important, and seemed like a non-useful thing to pursue, and if anything I’m on the flip side of that and am worried it and similar things were abandoned too quickly rather than too late.

Strong agreement with this. I remember being rather surprised and dismayed to hear that MIRI was pivoting away from agent foundations, and while I have more-than-substantial probability on them knowing something I don't, from my current vantage point I can't help but continue to feel that decision was premature.

My sense is that Eliezer and Nate (and I think some other researchers) updated towards shorter timelines in late 2016 / early 2017 ("moderately higher probability to AGI's being developed before 2035" in our 2017 update). This then caused them to think AF was less promising than they'd previously thought, because it would be hard to solve AF by 2035.

On their model, as I understand it, it was good for AF research to continue (among other things, because there was still a lot of probability mass on 'AGI is more than 20 years away'), and marginal AF progress was still likely to be useful even if we didn't solve all of AF. And MIRI houses a lot of different views, including (AFAIK) quite different views on the tractability of AF, the expected usefulness of AF progress, the ways in which solving AF would likely be useful, etc. This wasn't a case of 'everyone at MIRI giving up on AF', but it was a case of Eliezer and Nate (and some other researchers) deciding this wasn't where they should put their own time, because it didn't feel enough to them like 'the mainline way things end up going well'.

My simplified story is that in 2017-2020, the place Nate and Eliezer put their time was instead the new non-public research directions Benya Fallenstein had started (which coincided with a big push to hire more people to work with Nate/Eliezer/Benya/etc. on this). In late 2020 / early 2021, Nate and Eliezer decided that this research wasn't going fast enough, and that they should move on to other things (but they still didn't think AF was the thing). Throughout all of this, other MIRI researchers like Scott Garrabrant (the research lead for our AF work) have continued to chug away on AF / embedded agency work.

the ways in which solving AF would likely be useful

Other than the rocket alignment analogy and the general case for deconfusion helping, has anyone ever tried to describe with more concrete (though speculative) detail how AF would help with alignment? I'm not saying it wouldn't. I just literally want to know if anyone has tried explaining this concretely. I've been following for a decade but don't think I ever saw an attempted explanation.

Example I just made up:

- Modern ML is in some sense about passing the buck to gradient-descent-ish processes to find our optimizers for us. This results in very complicated, alien systems that we couldn't build ourselves, which is a worst-case scenario for interpretability / understandability.

- If we better understood how optimization works, we might able to do less buck-passing / delegate less of AI design to gradient-descent-ish processes.

- Developing a better formal model of embedded agents could tell us more about how optimization works in this way, allowing the field to steer toward approaches to AGI design that do less buck-passing and produce less opaque systems.

- This improved understandability then lets us do important alignment work like understanding what AGIs (or components of AGIs, etc.) are optimizing for, understanding what topics they're thinking about and what domains they're skilled in, understanding (and limiting) how much optimization they put into various problems, and generally constructing good safety-stories for why (given assumptions X, Y, Z) our system will only put cognitive work into things we want it to work on.

Thanks. This is great! I hadn't thought of Embedded Agency as an attempt to understand optimization. I thought it was an attempt to ground optimizers in a formalism that wouldn't behave wildly once they had to start interacting with themselves. But on second thought it makes sense to consider an optimizer that can't handle interacting with itself to be a broken or limited optimizer.

I think another missing puzzle piece here is 'the Embedded Agency agenda isn't just about embedded agency'.

From my perspective, the Embedded Agency sequence is saying (albeit not super explicitly):

- Here's a giant grab bag of anomalies, limitations, and contradictions in our whole understanding of reasoning, decision-making, self-modeling, environment-modeling, etc.

- A common theme in these ways our understanding of intelligence goes on the fritz is embeddedness.

- The existence of this common theme (plus various more specific interconnections) suggests it may be useful to think about all these problems in light of each other; and it suggests that these problems might be surprisingly tractable, since a single sufficiently-deep insight into 'how embedded reasoning works' might knock down a whole bunch of these obstacles all at once.

The point (in my mind -- Scott may disagree) isn't 'here's a bunch of riddles about embeddedness, which we care about because embeddedness is inherently important'; the point is 'here's a bunch of riddles about intelligence/optimization/agency/etc., and the fact that they all sort of have embeddedness in common may be a hint about how we can make progress on these problems'.

This is related to the argument made in The Rocket Alignment Problem. The core point of Embedded Agency (again, in my mind, as a non-researcher observing from a distance) isn't stuff like 'agents might behave wildly once they get smart enough and start modeling themselves, so we should try to understand reflection so they don't go haywire'. It's 'the fact that our formal models break when we add reflection shows that our models are wrong; if we found a better model that wasn't so fragile and context-dependent and just-plain-wrong, a bunch of things about alignable AGI might start to look less murky'.

(I think this is oversimplifying, and there are also more direct value-adds of Embedded Agency stuff. But I see those as less core.)

The discussion of Subsystem Alignment in Embedded Agency is I think the part that points most clearly at what I'm talking about:

[...] ML researchers are quite familiar with the phenomenon: it’s easier to write a program which finds a high-performance machine translation system for you than to directly write one yourself.

[...] Problems seem to arise because you try to solve a problem which you don't yet know how to solve by searching over a large space and hoping "someone" can solve it.

If the source of the issue is the solution of problems by massive search, perhaps we should look for different ways to solve problems. Perhaps we should solve problems by figuring things out. But how do you solve problems which you don't yet know how to solve other than by trying things?

I am struck by two elements of this conversation, which this post helped clarify did indeed stick out how I thought they did (weigh this lightly if at all, I'm speaking from the motivated peanut gallery here).

A. Eliezer's commentary around proofs has a whiff of Brouwer's intuitionism about it to me. This seems to be the case on two levels: first the consistent this is not what math is really about and we are missing the fundamental point in a way that will cripple us tone; second and on a more technical level it seems to be very close to the intuitionist attitude about the law of the excluded middle. That is to say, Eliezer is saying pretty directly that what we need is P, and not-not-P is an unacceptable substitute because it is weaker.

B. That being said, I think Steve Omohundro's observations about the provability of individual methods wouldn't be dismissed in the counterfactual world where they didn't exist; rather I expect that Eliezer would have included some line about how to top it all off, we don't even have the ability to prove our methods mean what we say they do, so even if we crack the safety problem we can still fuck it up at the level of a logical typo.

C. The part about incentives being bad for researchers which drives too much progress, and lamenting that corporations aren't more amenable to secrecy around progress, seems directly actionable and literally only requiring money. The solution is to found a ClosedAI (naturally not named anything to do with AI), go ahead and set those incentives, and then go around outbidding the FacebookAIs of the world for talent that is dangerous in the wrong hands. This has even been done before, and you can tell it will work because of the name: Operation Paperclip.

I really think Eliezer and co. should spend more time wish-listing about this, and then it should be solidified into a more actionable plan. Under entirely-likely circumstances, it would be easy to get money from the defense and intelligence establishments to do this, resolving the funding problem.

Thanks, your numbered list was very helpful in encouraging to go through the claims. Just two things that stood out to me:

39 Nothing we can do with a safe-by-default AI like GPT-3 would be powerful enough to save the world (to ‘commit a pivotal act’), although it might be fun. In order to use an AI to save the world it needs to be powerful enough that you need to trust its alignment, which doesn’t solve your problem.

- What exactly makes people sure that something like GPT would be safe/unsafe?

- If what is needed is some form of insight/break through: Some smarter version of GPT-3 seems really useful? The idea that GPT-3 produces better poetry than me while GPT-5 could help to come up with better alignment ideas, doesn't strongly conflict with my current view of the world?

Worth noting that the more precise #12 is substantially more optimistic than 12 as stated explicitly here.

#12:

“An aligned advanced AI created by a responsible project that is hurrying where it can, but still being careful enough to maintain a success probability greater than 25%, will take the lesser of (50% longer, 2 years longer) than would an unaligned unlimited superintelligence produced by cutting all possible corners.”

This might come across as optimistic if this was your median alignment difficulty estimate, but instead Elizier is putting 95% on this, which on the flip side suggests a 5% chance that things turn out to be easier. This seems rather in line with "Carefully aligning an AGI would at best be slow and difficult, requiring years of work, even if we did know how."

Nanosystems are definitely possible, if you doubt that read Drexler’s Nanosystems and perhaps Engines of Creation and think about physics.

Is there something like the result of a survey of experts about the feasibility of drexlerian nanotechnology? Are there any consensus among specialists about the possibility of a gray goo scenario?

Drexler and Yudkowsky both extremely overestimated the impact of molecular nanotechnology in the past.

not an expert, but I think life is an existence proof for the power of nanotech, even if the specifics of a grey goo scenario seem less than likely possible. Trees turn sunlight and air into wood, ribosomes build peptides and proteins, and while current generation models of protein folding are a ways from having generative capacity, it's unclear how many breakthroughs are between humanity and that general/generative capacity.

A survey of leading chemists would likely produce dismissals based on a strawmanned version of Drexler's ideas. If you could survey people who demonstrably understood Drexler, I'm pretty sure they'd say it's feasible, but critics would plausibly complain about selection bias.

The best analysis of gray goo risk seems to be Some Limits to Global Ecophagy by Biovorous Nanoreplicators, with Public Policy Recommendations.

They badly overestimated how much effort would get put into developing nanotech. That likely says more about the profitability of working on early-stage nanotech than it says about the eventual impact.

I don't think anyone (e.g., at FHI or MIRI) is worried about human extinction via gray goo anymore.

Drexler and Yudkowsky both extremely overestimated the impact of molecular nanotechnology in the past.

Like, they expected nanotech to come sooner? Or something else? (What did they say, and where?)

I don't think anyone (e.g., at FHI or MIRI) is worried about human extinction via gray goo anymore.

The fate of the concept of nanotechnology has been a curious one. You had the Feynman/Heinlein idea of small machines making smaller machines until you get to atoms. There were multiple pathways towards control over individual atoms, from the usual chemical methods of bulk synthesis, to mechanical systems like atomic force microscopes.

But I think Eric Drexler's biggest inspiration was simply molecular biology. The cell had been revealed as an extraordinary molecular structure whose parts included a database of designs (the genome) and a place of manufacture (the ribosome). What Drexler did in his books, was to take that concept, and imagine it being realized by something other than the biological chemistry of proteins and membranes and water. In particular, he envisaged rigid mechanical structures, often based on diamond (i.e. a lattice of carbons with a surface of hydrogen), often assembled in hard vacuum by factory-like nano-mechanisms, rather than grown in a fluid medium by redundant, fault-tolerant, stochastic self-assembly (as in the living cell).

Having seen this potential, he then saw this 'nanotechnology' as a way to do all kinds of transhuman things: make AI that is human-equivalent, but much smaller and faster (and hotter) than the human brain; grow a starship from a molecularly precise 3d printer in an afternoon; resurrect the cryonically suspended dead. And also, as a way to make replicating artificial life that could render the earth uninhabitable.

For many years, there was an influential futurist subculture around Drexler's thought and his institute, the Foresight Institute. And nanotechnology made it was into SF pop culture, especially the idea of a 'nanobot'. Nanobots are still there as an SF trope - and are sometimes cited as an inspiration in real research that involves some kind of controlled nanomechanical process - but I think it's unquestionable that the hype that surrounded that nano-futurist community has greatly diminished, as the years kept passing without the occurrence of the "assembler breakthrough" (ability to make the nonbiological nano-manufacturing agents).

There is a definite sense in which I think Eliezer eventually took up a place in culture analogous to that once held by Eric Drexler. Drexler had articulated a techno-eschatology in which the entire future revolved around the rise of nanotechnology (and his core idea for how humanity could survive was to spread into space; he had other ideas too, but I'd say that's the essence of his big-picture strategy), and it was underpinned not just by SF musings but also by nanomachine designs, complete with engineering calculations. With Eliezer, the crucial technology is artificial intelligence, the core idea is alignment versus extinction via (e.g.) paperclip maximizer, and the technical plausibility arguments come from computer science rather than physics.

Those who are suspicious of utopian and dystopian thought in general, including their technologically motivated forms, are happy to say that Drexler's extreme nano-futurology faded because something about it was never possible, and that the same fate awaits Eliezer's extreme AI-futurology. But as for me, I find the arguments in both cases quite logical. And that raises the question, even as we live through a rise in AI capabilities that is keeping Eliezer's concerns very topical, why did Drexler's nano-futurism fade... not just in the sense that e.g. the assembler breakthrough never became a recurring topic of public concern, the way that climate change did; but also in the sense that, e.g., you don't see effective altruists worrying about the assembler breakthrough, and this is entirely because they are living in the 2020s; if effective altruism had existed in the 1990s, there's little doubt that gray goo and nanowar would have been high in the list of existential risks.

Understanding what happened to Drexler's nano-futurism requires understanding what kind of 'nano' or chemical progress has occurred since those days, and whether the failure of certain things to eventuate is because they are impossible, because not enough of the right people were interested, because the relevant research was starved of funds and suppressed (but then, by who, how, and why), or because it's hard and we didn't cross the right threshold yet, the way that artificial neural networks couldn't really take off until the hardware for deep learning existed.

It seems clear that 'nanotechnology' in the form of everything biological, is still developing powerfully and in an uninhibited way. The Covid pandemic has actually given us a glimpse of what a war against a nano-replicator is like, in the era of a global information society with molecular tools. And gene editing, synthetic biology, organoids, all kinds of macabre cyborgian experiments on lab animals, etc, develop unabated in our biotech society.

As for the non-biological side... it was sometimes joked that 'nanotechnology' is just a synonym for 'chemistry'. Obviously, the world of chemical experiment and technique, quantum manipulations of atoms, design of new materials - all that continues to progress too. So it seems that what really hasn't happened, is that specific vision of assemblers, nanocomputers, and nanorobots made from diamond-like substances.

Again, one may say: it's possible, it just hasn't happened yet for some reason. The world of 2D carbon substances - buckyballs, buckytubes, graphenes - seems to me the closest that we've come so far. All that research is still developing, and perhaps it will eventually bootstrap its way to the Drexlerian level of nanotechnology, once the right critical thresholds are passed... Or, one might say that Eric's vision (assemblers, nanocomputers, nanorobots) will come to pass, without even requiring "diamondoid" nanotechnology - instead it will happen via synthetic biology and/or other chemical pathways.

My own opinion is that the diamondoid nanotechnology seems like it should be possible, but I wonder about its biocompatibility - a crucial theme in the nanomedical research of Robert Freitas, who was the champion of medical applications as envisaged by Drexler. I am just skeptical about the capacity of such systems to be useful in a biochemical environment. Speaking of astronomically sized intelligences, Stanislaw Lem once wrote that "only a star can survive among stars", meaning that such intelligences should have superficial similarities to natural celestial bodies, because they are shaped by a common physical regime; and perhaps biomedically useful nanomachines must necessarily resemble and operate like the protein complexes of natural biology, because they have to work in that same regime of soluble biopolymers.

Specifically with respect to 'gray goo', i.e. nonbiological replicators that eat the ecosphere (keywords include 'aerovore' and 'ecophagy'), it seems like it ought to be physically possible, and the only reason we don't need to worry so much about diamondoid aerovores smothering the earth, is that for some reason, the diamondoid kind of nanotechnology has received very little research funding.

Fascinating history, Mitchell! :) I share your confusion about why more EAs aren't interested in Drexlerian nanotech, but are interested in AGI.

I would indeed guess that this is related to the deep learning revolution making AI-in-general feel more plausible/near/real, while we aren't experiencing an analogous revolution that feels similarly relevant to nanotech. That is, I don't think it's mostly based on EAs having worked out inside-view models of how far off AGI vs. nanotech is.

I'd guess similar factors are responsible for EAs being less interested in whole-brain emulation? (Though in that case there are complicating factors like 'ems have various conceptual and technological connections to AI'.)

Alternatively, it could be simple founder effects -- various EA leaders do have various models saying 'AGI is likely to come before nanotech or ems', and then this shapes what the larger community tends to be interested in.

Specifically with respect to 'gray goo', i.e. nonbiological replicators that eat the ecosphere (keywords include 'aerovore' and 'ecophagy'), it seems like it ought to be physically possible, and the only reason we don't need to worry so much about diamondoid aerovores smothering the earth, is that for some reason, the diamondoid kind of nanotechnology has received very little research funding.

From Drexler's conversation with Open Phil:

Dr. Drexler suggests that the nature of the technologies (essentially small-scale chemistry and mechanical devices) creates no risk from large scale unintended physical consequences of APM. In particular the popular “grey goo” scenario involving self-replicating, organism-like nanostructures has nothing to do with factory-style machinery used to implement APM systems. Dangerous products could be made with APM, but would have to be manufactured intentionally.

No one has a reason to build grey goo (outside of rare omnicidal crazy people), so it's not worth worrying about, unless someday random crazy people can create arbitrary nanosystems in their background.

AGI is different because it introduces (very powerful) optimization in bad directions, without requiring any pre-existing ill intent to get the ball rolling.

And that raises the question, even as we live through a rise in AI capabilities that is keeping Eliezer's concerns very topical, why did Drexler's nano-futurism fade...

One view I've seen is that perverse incentives did it. Widespread interest in nanotechnology led to governmental funding of the relevant research, which caused a competition within academic circles over that funding, and discrediting certain avenues of research was an easier way to win the competition than actually making progress. To quote:

Hall blames public funding for science. Not just for nanotech, but for actually hurting progress in general. (I’ve never heard anyone before say government-funded science was bad for science!) “[The] great innovations that made the major quality-of-life improvements came largely before 1960: refrigerators, freezers, vacuum cleaners, gas and electric stoves, and washing machines; indoor plumbing, detergent, and deodorants; electric lights; cars, trucks, and buses; tractors and combines; fertilizer; air travel, containerized freight, the vacuum tube and the transistor; the telegraph, telephone, phonograph, movies, radio, and television—and they were all developed privately.” “A survey and analysis performed by the OECD in 2005 found, to their surprise, that while private R&D had a positive 0.26 correlation with economic growth, government funded R&D had a negative 0.37 correlation!” “Centralized funding of an intellectual elite makes it easier for cadres, cliques, and the politically skilled to gain control of a field, and they by their nature are resistant to new, outside, non-Ptolemaic ideas.” This is what happened to nanotech; there was a huge amount of buzz, culminating in $500 million dollars of funding under Clinton in 1990. This huge prize kicked off an academic civil war, and the fledgling field of nanotech lost hard to the more established field of material science. Material science rebranded as “nanotech”, trashed the reputation of actual nanotech (to make sure they won the competition for the grant money), and took all the funding for themselves. Nanotech never recovered.

Source: this review of Where's My Flying Car?

One wonders if similar institutional sabotage of AI research is possible, but we're probably past the point where that might've worked (if that even was what did nanotech in).

I guess I missed the term gray goo. I apologize for this and for my bad English.

Is it possible to replace it on the 'using nanotechnologies to attain a decisive strategic advantage'?

I mean the discussion of the prospects for nanotechnologies on SL4 20+ years ago. This is especially:

My current estimate, as of right now, is that humanity has no more than a 30% chance of making it, probably less. The most realistic estimate for a seed AI transcendence is 2020; nanowar, before 2015.

I understand that since then the views of EY have changed in many ways. But I am interested in the views of experts on the possibility of using nanotechnology for those scenarios that he implies now. That little thing I found.

I really like this post format - a numbered list of beliefs that come together to form a model - it makes the model very clear, makes it easier to see where you differ and what the cruxes are, and makes it easier to discuss.

39. Nothing we can do with a safe-by-default AI like GPT-3 would be powerful enough to save the world (to ‘commit a pivotal act’), although it might be fun. In order to use an AI to save the world it needs to be powerful enough that you need to trust its alignment, which doesn’t solve your problem.

I think a weak proto-AI could be useful for step 1 of the following plan:

- Invent some human-enhancement methods to massively amplify the abilities of your researchers.

- Use your enhanced researchers to make a friendly AGI faster than your competitors make any AGI.

Some human-enhancement ideas sitting in my mind:

- reducing or removing the need for sleep or exercise

- reversing age-related cognitive decline (and physical decline for that matter)

- electronically facilitated brain-to-brain communication

- brain-computer interfaces that are faster and less effortful than keyboards or screens

- drugs altering brain chemistry so you think faster or better (e.g. is there any measurable chemical difference between average brains and geniuses' brains? If so, can you use drugs to make the one work like the other?)

- enlarging heads via surgery and growing more brain cells (this is slightly horrifying)

- getting something close to The Matrix's "downloading skills into your brain"—teaching modules that observe your brain-state, possibly alter it directly, and possibly implant some hardware whose interface your brain learns

It seems like any one of these, if it worked, might give you the 1.5x factor mentioned (or more), assuming your competitors didn't adopt it quickly enough. (Would they? I don't think I could see a normal company requiring all its researchers to go through these enhancement procedures in, say, less than a few years after they'd been developed; nor Western governments. China, maybe.) A proto-AI is not necessary for any of them, but it might be the fastest way.

I like the idea of enhanced researchers for a few reasons:

- going off Fred Brooks's "The Mythical Man-Month", a smallish group of enhanced researchers might outperform arbitrarily large groups of "normal" humans

- leaks, and other "unilateralist's curse" issues, are less of an issue with smaller groups

- at least for some of these enhancements, the programmers would be less likely to make bugs/mistakes, and therefore, if there are situations where "one stupid bug makes the difference between success and failure", we'd have a better chance

- the rest of humanity would benefit from these enhancement techniques too

The human enhancement part of this would need to move really really really fast to beat the AGI power scaling and proliferation timelines.

Hmm, that seems to depend on what assumptions you make. Suppose it takes N years to develop proto-AI to the point where it can find a sleep-mimicking drug, and after that it would take M more years to develop general AI, and M * 1.5 more years to develop friendly general AI. If M is much higher than how long it takes for the FAI researchers to start using the drug (which I imagine could be a few months), then the FAI researchers might be enhanced for most of the M-year period before competitors make AGI.

I think you're assuming M is really low. My intuition is that many of these enhancements wouldn't require much more than a well-funded team and years of work with today's technology (but fewer years with proto-AI), and that N is much smaller than M. But this depends a lot on the details of the enhancement problems and on the current state of biotechnology and bioinformatics, and I don't know very much. Are there people associated with MIRI and such who work on human bioenhancement?

For 1 (probability of AGI) in particular: I think in addition to probably thinking inside view that AGI is harder than Eliezer/MIRI think it is, I also think civilization’s dysfunctions are more likely to disrupt things and make it increasingly difficult to do anything at all, or anything new/difficult, and also collapse or other disasters. I know Nate Sores explicitly rejects this mattering much, but it matters inside view to me quite a bit.

I'd like to believe this, but the coronavirus disaster gives me pause. Seems like the ONE relevant bit of powerful science/technology that wasn't heavily restricted or outright banned was gain-of-function research, which may or may not have been responsible for the whole mess in the first place (and certainly raises the danger of it happening again).

And I notice that the same forces/people/institutions who unpersuasively defend the FDA's anti-vaccine policies unpersuasively defend the legality of GoF... I honestly don't have any model of what's going on there — and what these forces/people/institutions said about the White House's push boosters convinces me it is more complicated than instinctively aligning with authority, power, or partisan interests. Does anyone have a model for this?

But in lieu of real understanding: I don't think we can count on our civilizational dysfunction to accidentally coincidentally help us here. If our civilization can't manage stop GoF, while it simultaneously outlaws vaccines and HCTs, I don't think we should expect it do slow down AI by very much.

I don't literally expect the scenario where, say... the outrage machine calls for banning AI Alignment research and successfully restricts it, while our civilization feverishly pours all of its remaining ability to Do into scaling AI. But I don't expect it to be much better than that, from a civilizational competence point of view. (At least not on the current path, and I don't currently see any members of this community making any massive heroic efforts to change that that look like they will actually succeed.)

In the post this is called a ‘miracle’ but this has misleading associations – it was not meant to imply a negligible probability, only surprise, so Rob suggested changing it to ‘surprising positive development.’

How about the phrase "positive model violation"? Later in that post Eliezer is recorded as saying:

a miracle that violates some aspect of my background model ... positive model violation ("miracle")

I think "model violation" and "surprising development" point to different things. For example:

- If I buy a lottery ticket and win a million dollars from the lottery, that is a "surprising development". If I don't buy a lottery ticket and still win a million dollars from the lottery, that is also a "model violation", as it violates our model of how lotteries work.

- If my nemesis is struck by lightning from the sky, that is a "surprising development". If my nemesis is struck by lightning cast by a magic wand, that is also a "model violation", as it violates our model of lightning.

- If many AI researchers independently decide to switch to safety work, that is a "surprising development". If corrigibility turns out to be "natural" for an AI, that is also a "model violation" of (my model of) Eliezer's models of corrigibility and intelligence.

My models of lightning and lotteries are relatively robust, and the model violations are negligible probability. Models of the future of AI development and intelligence and geo-politics and human nature and so forth are presumably much weaker, so we can reasonably expect some model violations, positive and negative.

From what I've seen in discussions over the future of humanity, the following options are projected, from worst to best:

- Collapse of humanity due to AGI taking over and killing everyone

- Collapse of humanity, but some humans remain alive in "The Matrix" or "zoo" of some kind

- Collapse due to existing technology like nuclear bombs

- Collapse due to climate change or meteor or mega-volcano or alien invasion

- Collapse due to exhausting all useful elements and sources of energy

- Reversal to pre-20th century levels and stagnation due to combination of 2/3/4

- Stagnation at 21st century level tech

- Stagnation at a non-crazy level of tech - say good enough to have a colony on Pluto, but no human ever leaving the Solar system

- Interstellar civ based on "virtual humans"/"brains in a jar"

- Interstellar civ run by fully aligned AGI, with human intelligence being so weak that it basically plays no role

- Interstellar civilization primarily based on human intelligence (Star Trek pre-Data?)

- Interstellar civ based on humans+AGI working together peacefully (Star Trek's implied future given Data's evolution?)

- Multiverse civilization of some kind (Star Trek's Q?)

Is this ranking approximately correct? If so, why do we care so much if "AGI" or "virtual humans" end up ruling the universe? Does it make a difference if the AGI is based on human intelligence and not on some alien brain structure, given that biological humans will stagnate/die out in both cases? Or is "virtual humans" just as bad of an outcome and falls into the same bucket of "unaligned AGI"? What goal are we truly trying to optimize here?

Previously (see Hanson/Eliezer FOOM debate) Eliezer thought you’d need recursive self-improvement first to get fast capability gain, and now it looks like you can get fast capability gain without it, for meaningful levels of fast. This makes ‘hanging out’ at interesting levels of AGI capability at least possible, since it wouldn’t automatically keep going right away.

Might be good to elaborate on this one a bit, why that might make 'hanging out' possible, i.e., diminishing returns. (Though if a substantial improvement can be made by a) tweaks, b) adding another technique or something, then maybe 'hanging out' won't happen.)

Hiding what you are doing is a convergent instrumental strategy.

Amusingly, true on two levels. (Though there's worry, people won't converge on that strategy anyway.)

Explanation of above part 2: Corrigibility is ‘anti-natural’ in a certain sense that makes it incredibly hard to, eg, exhibit any coherent planning behavior (“consistent utility function”) which corresponds to being willing to let somebody else shut you off, without incentivizing you to actively manipulate them to shut you off).

Sort of 'corrigibility' is 'Corrigibility without (something like) self-shutdown or self-destruct.'

37. Trying to hardcode nonsensical assumptions or arbitrary rules into an AGI will fail because a sufficiently advanced AGI will notice that they are damage and route around them or fix them (paraphrase).

Is this about strategy/techniques, or reward?

39. Nothing we can do with a safe-by-default AI like GPT-3 would be powerful enough to save the world (to ‘commit a pivotal act’), although it might be fun. In order to use an AI to save the world it needs to be powerful enough that you need to trust its alignment, which doesn’t solve your problem.

And it's not particularly useful for convincing people to do things like 'not publish'.

They’re a core thing one could and should ask an AI/AGI to build for you in order to accomplish the things you want to accomplish.

(I expected a caveat here, like 'if aligned'.)

43. Furthermore, an unaligned AGI powerful enough to commit pivotal acts should be assumed to be able to hack any human foolish enough to interact with it via a text channel.

What are pivotal acts, aside from 'persuading people'? Nanotech, or is the bar lower?

Proving theorems about the AGI doesn’t seem practical.

Is proving things useful to 'ai'? Like, in Go, or Starcraft? Or are strategies always not handled that way?

>Which is basically this: I notice my inside view, while not confident in this, continues to not expect current methods to be sufficient for AGI, and expects the final form to be more different than I understand Eliezer/MIRI to think it is going to be, and that theAGI problem (not counting alignment, where I think we largely agree on difficulty) is ‘harder’ than Eliezer/MIRI think it is.

Could you share why you think that current methods are not sufficient to produce AGI?

Some context:

After reading Discussion with Eliezer Yudkowsky on AGI interventions I thought about the question "Are current methods sufficient to produce AI?" for a while. I thought I'd check if neural nets are Turing-complete and quick search says they are. To me this looks like a strong clue that we should be able to produce AGI with current methods.

But I remembered reading some people who generally seemed better informed than me having doubts.

I'd like to understand what those doubts are (and why there is apparent disagreement on the subject).

I want to be clear that my inside view is based on less knowledge and less time thinking carefully, and thus has less and less accurate gears, than I would like or than I expect to be true of many others' here's models (e.g. Eliezer).

Unpacking my reasoning fully isn't something I can do in a reply, but if I had to say a few more words, I'd say it's related to the idea that the AGI will use qualitatively different methods and reasoning, and not thinking that current methods can get there, and that we're getting our progress out of figuring out how to do more and more things without thinking in this sense, rather than learning how to think in this sense, and also finding out that a lot more of what humans do all day doesn't require thinking - I felt like GPT-3 taught me a lot about humans and how much they're on autopilot and how they still get along fine, and I went through an arc where it seemed curious, then scary, then less scary on this front.

I'm emphasizing that this is intuition pumping my inside view, rather than things I endorse or think should persuade anyone, and my focus very much was elsewhere.

Echo the other reply that Turing complete seems like a not-relevant test.

I have only a very vague idea what are different reasoning ways (vaguely related to “fast and effortless “ vs “slow and effortful in humans? I don’t know how that translates into what’s actually going on (rather than how it feels to me)).

Thank you for pointing me to a thing I’d like to understand better.

Turing completeness is definitely the wrong metric for determining whether a method is a path to AGI. My learning algorithm of "generate a random Turing machine, test it on the data, and keep it if it does the best job of all the other Turing machines I've generated, repeat" is clearly Turing complete, and will eventually learn any computable process, but it's very inefficient, and we shouldn't expect AGI to be generated using that algorithm anytime in the near future.

Similarly, neural networks with one hidden layer are universal function approximators, and yet modern methods use very deep neural networks with lots of internal structure (convolutions, recurrences) because they learn faster, even though a single hidden layer is enough in theory to achieve the same tasks.

I was thinking that current methods could produce AGI (because Turing-complete) and they can apparently good at producing some algorithms so they might be reasonably good at producing AGI.

2nd part of that wasn't explicit for me before your answer so thank you :)

I don't see any glaring flaws in any of the items on the inside view, and, obviously, I would not be qualified to evaluate them, anyway. However, when I try to take an outside view on this, something doesn't add up.

Specifically, it looks like anything that looks like a civilization should end up evolving, naturally or artificially, into an unsafe AGI most of the time, some version of Hanson's grabby aliens. We don't see anything like that, at least not in any detectable way. And so we hit the Fermi paradox, where an unremarkable backwater system is apparently the first one about to do so, many billions of years after the Big Bang. It is not outright impossible, but the odds do not match up with anything presented by Eliezer. Hanson's reason for why we don't see grabby aliens is < 1/10,000 "conversion rate" of "non-grabby to grabby transition":

assuming a generous million year average duration for non-grabby civilizations, depressingly low transition chances p are needed to estimate that even one other one was ever active anywhere along our past lightcone (p <∼10−3) , has ever existed in our galaxy (p <∼10−4) , or is active now in our galaxy (p <∼10−7) . Such low chances p would bode badly for humanity’s future

However, an unaligned AGI that ends humanity ought to have a much higher chance of transition into grabbiness than that, so there is a contradiction between the predictions of unsafe AGI takeover and the lack of evidence of it happening in our past lightcone.

Low conversion rate to grabbiness is only needed in the model if you think there are non-grabby aliens nearby. High conversion rate is possible if the great filter is in our past and industrial civilizations are incredibly rare.

You haven't commented much on Eliezer's views on the social approach to slow down the development of AGI - the blocks starting with

I don't know how to effectively prevent or slow down the "next competitor" for more than a couple of years even in plausible-best-case scenarios.

and

I don't want to sound like I'm dismissing the whole strategy, but it sounds a lot like the kind of thing that backfires because you did not get exactly the public reaction you wanted

What's your take on this?

On slowing down, I'd say strong inside view agreement, I don't see a way either, not without something far more universal. There's too many next competitors. Could have been included, probably excluded due to seeming like it followed from other points and was thus too obvious.

On the likelihood of backfire, strong inside view agreement. Not sure why that point didn't make it into the post, but consider this an unofficial extra point (43?), of something like (paraphrase, attempt 1) "Making the public broadly aware of and afraid of these scenarios is likely to backfire and result in counterproductive action."

On the object level it looks like there are a spectrum of society-level interventions starting from "incentivizing research that wouldn't be published" (which is supported by Eliezer) and all the way to "scaring the hell out of general public" and beyond. For example, I can think of removing $FB and $NVDA from ESGs, disincentivizing publishing code and research articles in AI, introducing regulation of compute-producing industry. Where do you think the line should be drawn between reasonable interventions and ones that are most likely to backfire?

On the meta level, the whole AGI foom management/alignment starts not some abstract 50 years in the future, but right now, with the managing of ML/AI research by humans. Do you know of any practical results produced by alignment research community that can be used right now to manage societal backfire / align incentives?

RE: claim 25 about the need for research organisations , my first thought is that government national security organisations might be suitable venues for this kind of research as they have several apparent advantages:

- Large budgets

- Existing culture and infrastructure for research in secret with internal compartmentalisation

- Comparatively good track record for keeping results secret in crypto, such as the NSA with RSA or GCHQ with PGP

- Routes to internal prestige and advancement without external publication

- Preventing the creation of unaligned AI would accord with their national security goals

However, they may introduce problems of their own:

- Clearance requirements limit the talent pool that can work with them

- As government organisations with less of a start-up culture, they may be less accommodating of this kind of research

- An information leak that one organisation is researching this area could lead to international arms races

- Tools suitable for public release that are developed may be seen as untrustworthy by association, such as the skepticism towards the NSA's crypto advice

- A research group would be more beholden to higher-ups who would likely be less sympathetic to the necessity of alignment work compared to capability work

Has this option been discussed already?

Some people here inspire me to make predictions ;) So here's my attempt:

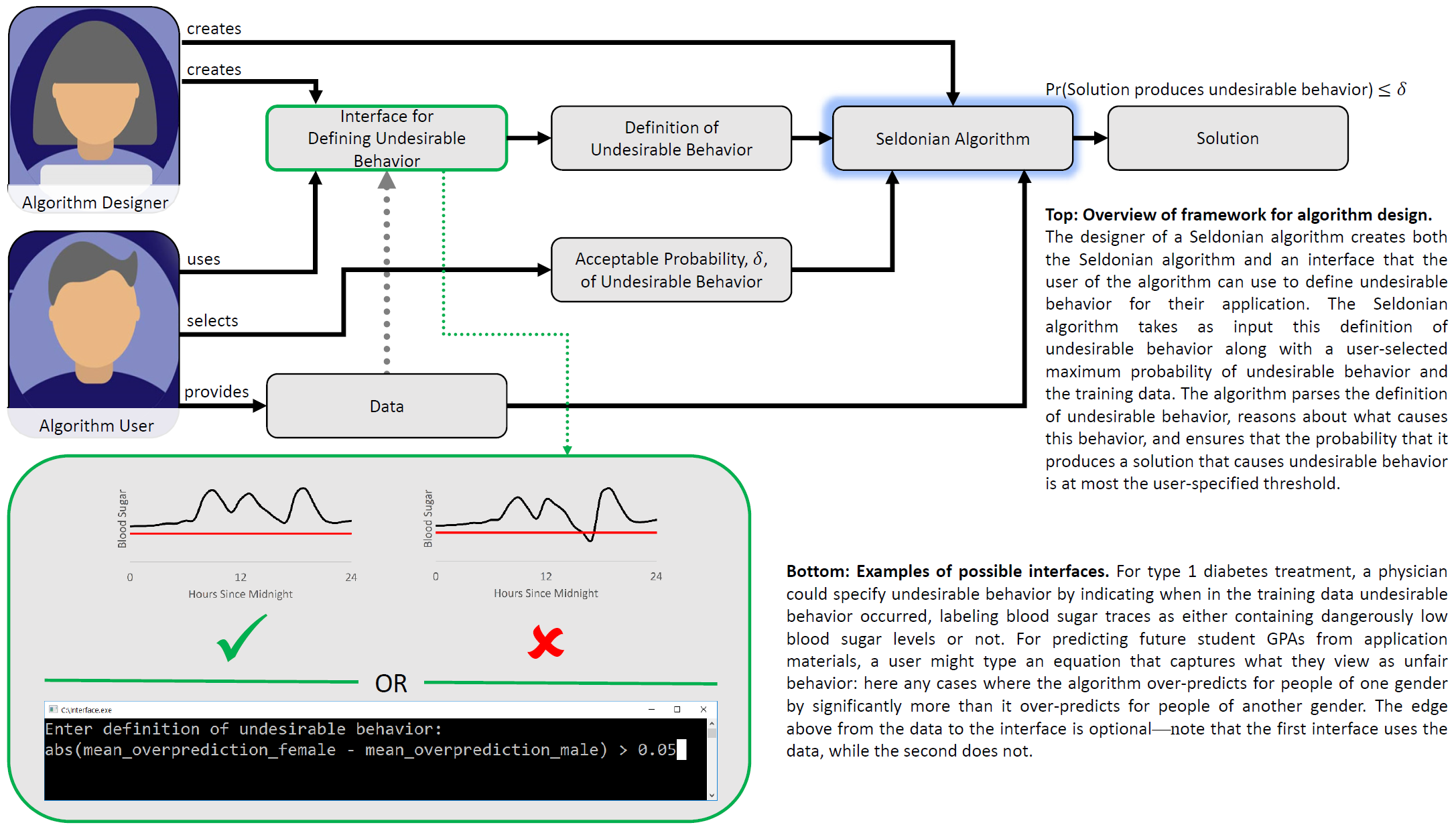

My guess, mainly based on this image (linked from the post):

Is that he'd say it's a sub category of "getting models to output things based only on their training data, while treating them as a black box and still assuming unexpected outputs will happen sometimes", as well as "this might work well for training, but obviously not for an AGI" and "if we're going to talk about limiting a model's output, Redwood Research is more of a way to go" and perhaps "this will just advance AI faster"

I agree that "think for yourself" is important. That includes updating on the words of the smart thinkers who read a lot of the relevant material. In which category I include Zvi, Eliezer, Nate Soares, Stuart Armstrong, Anders Sandberg, Stuart Russell, Rohin Shah, Paul Chistiano, and on and on.

Recently, a discussion of potential AGI interventions and potential futures was posted to LessWrong. The picture Eliezer presented was broadly consistent with my existing model of Eliezer’s model of reality, and most of it was also consistent with my own model of reality.

Those two models overlap a lot, but they are different and my model of Eliezer strongly yells at anyone who thinks they shouldn’t be different that Eliezer wrote a technically not infinite but rather very large number of words explaining that you need to think for real and evaluate such things for yourself. On that, our models definitely agree.

It seemed like a useful exercise to reread the transcript of Eliezer’s discussion, and explicitly write out the world model it seems to represent, so that’s what I’m going to do here.

Here are some components of Eliezer’s model, directly extracted from the conversation, rewritten to be third person. It’s mostly in conversation order but a few things got put in logical order.

Before publishing, I consulted with Rob Bensinger, who helped refine several statements to be closer to what Eliezer actually endorses. I explicitly note the changes where they involve new info, so it’s clear what is coming from the conversation and what is coming from elsewhere. In other places it caused me to clean up my wording, which isn’t noted. It’s worth pointing out that the corrections often pointed in the ‘less doom’ direction, both in explicit claims and in tone/implication, so chances are this comes off as generally implying more doom than is appropriate.

Now to put the core of that into simpler form, and excluding non-central details, in a more logical order.

Again, this is my model of Eliezer’s model, statements are not endorsed by me, I agree with many but not all of them.

Worth noting that the more precise #12 is substantially more optimistic than 12 as stated explicitly here.

Looking at these 42 claims, I notice my inside view mostly agrees, and would separate them into:

Inside view disagreement but seems plausible: 1

Inside view lacks sufficient knowledge to offer an opinion: 28 (I haven’t looked for myself)

Inside view isn’t sure: 8 (if we add ‘using current ideas’ move to strong agreement), 13, 36

Weak inside view agreement – seems probably true not counting Eliezer’s opinion, but I wouldn’t otherwise be confident: 7, 9, 10, 22, 34, 35, 40

Strong inside view agreement: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 12 (original version would be weak agreement, revised version is strong agreement), 14 (conditional on 13), 15, 16 (including the stronger version), 17, 18, 19 (in general, not for specific people), 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 37, 38, 39 (unless a bunch of other claims also break first), 41, 42

Thus, I have inside view agreement (e.g. I substantively agree with this picture without taking into account anyone’s opinion) on 37 of the 42 claims, including many that I believe to be ‘non-obvious’ on first encounter.

That leaves 5 remaining claims.

For 28 (Nanotechnology) I think it’s probably true, but I notice I’m counting on others models of the technology that would be involved, so I want to be careful to avoid information cascade, but my outside view strongly agrees.

For 8 (Safe AIs lack the power to save us) would require a surprising positive development for it to be wrong, in the sense that no currently proposed methods seem like they’d work. But I notice I instinctively remain hopeful for such a development, and for a solution to be found. I’m not sure how big a disagreement exists here, there might not be one.

That leaves 1 (85% AGI by 2070), 13 (AGI is a giant pile of floating-point vectors) and 36 (Agent Foundations and similar are dead ends) which are largely the same point of doubt.

Which is basically this: I notice my inside view, while not confident in this, continues to not expect current methods to be sufficient for AGI, and expects the final form to be more different than I understand Eliezer/MIRI to think it is going to be, and that theAGI problem (not counting alignment, where I think we largely agree on difficulty) is ‘harder’ than Eliezer/MIRI think it is.

For 36 (Agent Foundations) in particular: I notice a bunch of people in the comments saying Agent Foundations isn’t/wasn’t important, and seemed like a non-useful thing to pursue, and if anything I’m on the flip side of that and am worried it and similar things were abandoned too quickly rather than too late. It’s a case of ‘this probably will do nothing and look stupid but might do a lot or even be the whole ballgame’ and that being hard to sustain even for a group like MIRI in such a spot, but being a great use of resources in a world where things look very bad and all solutions assume surprising (and presumably important) positive developments. Everybody go deep.

For 1 (probability of AGI) in particular: I think in addition to probably thinking inside view that AGI is harder than Eliezer/MIRI think it is, I also think civilization’s dysfunctions are more likely to disrupt things and make it increasingly difficult to do anything at all, or anything new/difficult, and also collapse or other disasters. I know Nate Sores explicitly rejects this mattering much, but it matters inside view to me quite a bit. I don’t have an inside view point estimate, but if I could somehow bet utility (betting money really, really doesn’t work here, at all) and could only bet once, I notice I’d at least buy 30% and sell 80%, or something like that.

Also, I noticed two interrelated things that I figured are worth noting from the comments: