There's a lot of discourse around abrupt generalization in models, most notably the "sharp left turn." Most recently, Wei et al. 2022 claim that many abilities suddenly emerge at certain model sizes. These findings are obviously relevant for alignment; models may suddenly develop the capacity for e.g. deception, situational awareness, or power-seeking, in which case we won't get warning shots or a chance to practice alignment. In contrast, prior work has also found "scaling laws" or predictable improvements in performance via scaling model size, data size, and compute, on a wide variety of domains. Such domains include transfer learning to generative modeling (on images, video, multimodal, and math) and reinforcement learning. What's with the discrepancy?

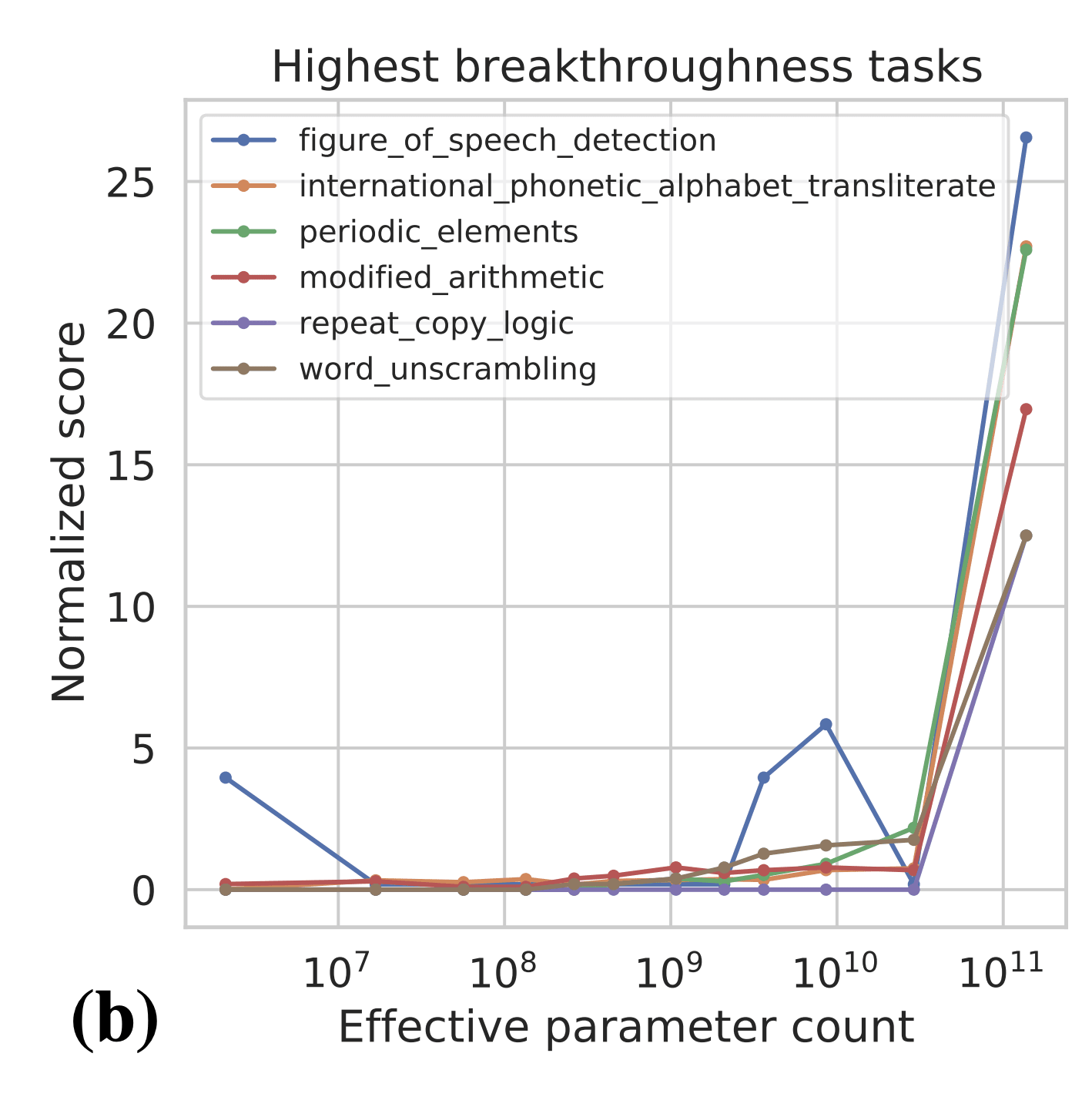

One important point is the metric that people are using to measure capabilities. In the BIG Bench paper (Figure 7b), the authors find 7 tasks that exhibit "sharp upwards turn" at a certain model size.

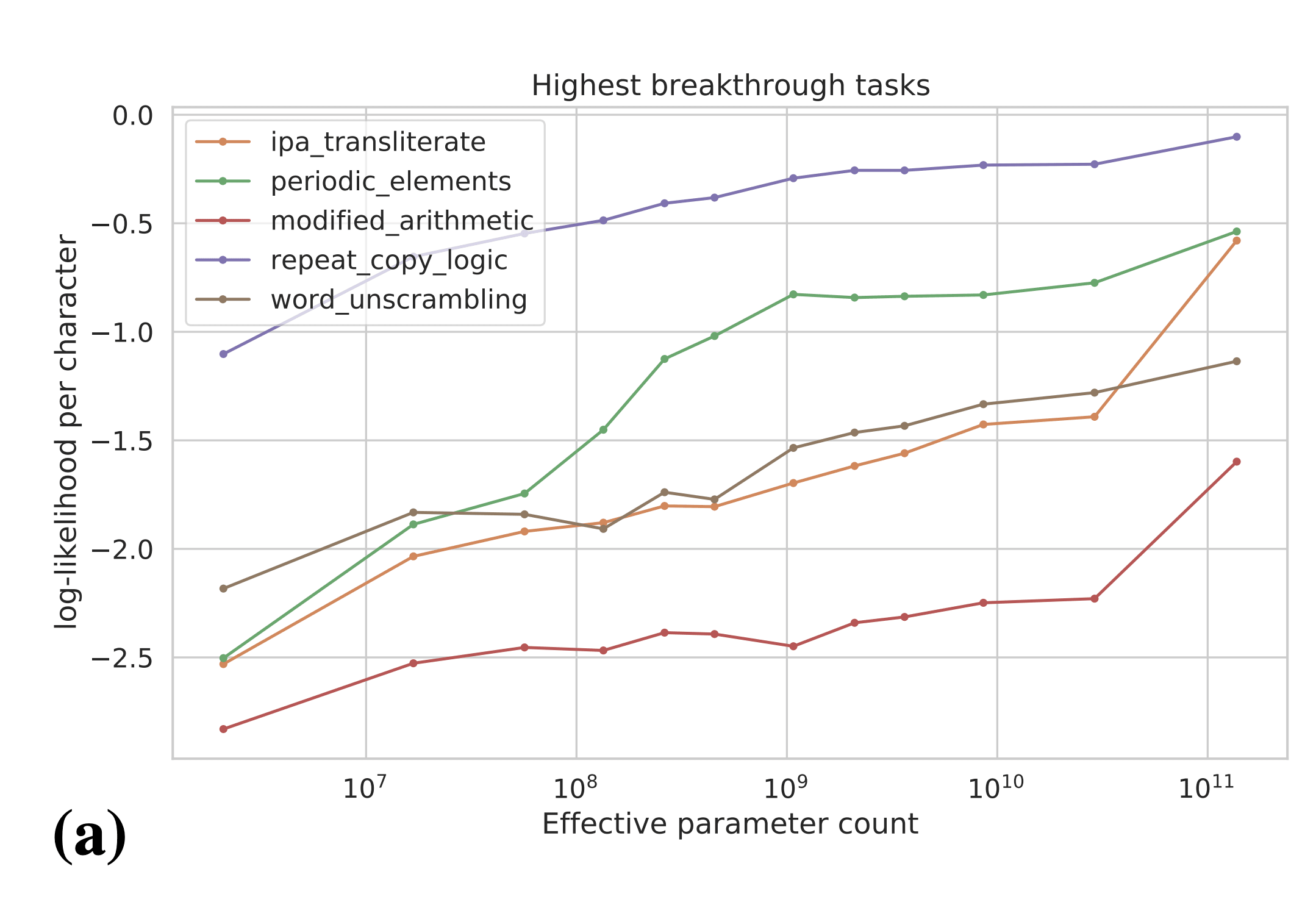

Naively, the above results are evidence for sharp left turns, and the above tasks seem like some of the best evidence we have for sharp left turns. However, the authors plot the results on the above tasks in terms of per-character log-likelihood of answer:

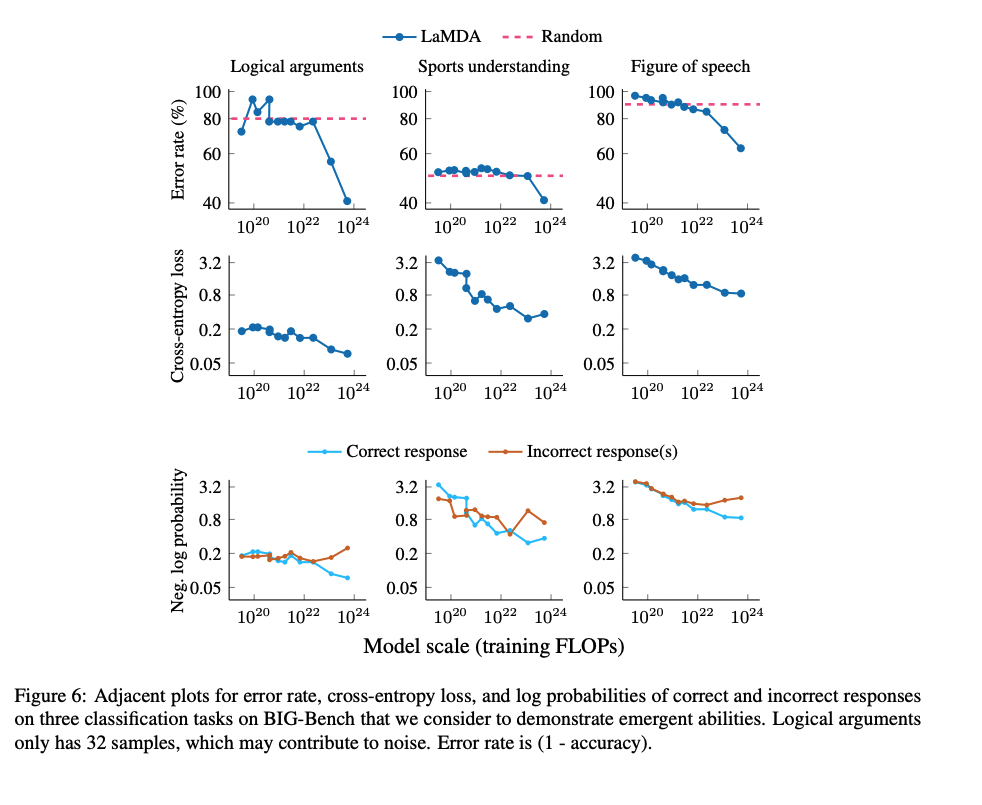

The authors actually observe smooth increases in answer log-likelihood, even for tasks which showed emergent behavior according to the natural performance metric for the task (e.g. accuracy). These results are evidence that we can predict that emergent behaviors will occur in the future before models are actually "capable" of those behaviors. In particular, these results suggest that we may be able to predict power-seeking, situational awareness, etc. in future models by evaluating those behaviors in terms of log-likelihood. We may even be able to experiment on interventions to mitigate power-seeking, situational awareness, etc. before they become real problems that show up in language model -generated text.

Clarification: I think we can predict whether or not a sharp left turn towards deception/misalignment will occur rather than exactly when. In particular, I think we should look at the direction of the trend (increases vs. decreases in log-likelihood) as signal about whether or not some scary behavior will eventually emerge. If the log likelihood of some specific scary behavior increases, that’s a bad sign and gives us some evidence it will be a problem in the future. I mainly see scaling laws here as a tool for understanding and evaluating which of the hypothesized misalignment-relevant behaviors will show up in the future. The scaling laws are useful signal for (1) convincing ML researchers to worry about scaling up further because of alignment concerns (before we see them in model behaviors/outputs) and (2) guiding alignment researchers with some empirical evidence about which alignment failures are likely/unlikely to show up after scaling at some point.

Big-Bench would appear to provide another instance of this in the latest PaLM inner-monologue paper, "Challenging BIG-Bench Tasks and Whether Chain-of-Thought Can Solve Them", Suzgun et al 2022: they select a subset of the hardest feasible-looking BIG-Bench tasks, and benchmark PaLM on them. No additional training, just better prompting on a benchmark designed to be as hard as possible. Inner-monologue prompts, unsurprisingly by this point, yields considerable improvement... and it also changes the scaling for several of the benchmarks - what looks like a flat scaling curve with the standard obvious 5-shot benchmark prompt can turns out to be a much steeper curve as soon as they use the specific chain-of-thought prompt. (For example, "Web of Lies" goes from a consistent random 50% at all model sizes to scaling smoothly from ~45% to ~100% performance.) And I don't know any reason to think that CoT is the best possible inner-monologue prompt for PaLM, either.

"Sampling can show the presence of knowledge but not the absence."