In terms of content, this has a lot of overlap with Reward is not the optimization target. I'm basically rewriting a part of that post in language I personally find clearer, emphasising what I think is the core insight.

When thinking about deception and RLHF training, a simplified threat model is something like this:

- A model takes some actions.

- If a human approves of these actions, the human gives the model some reward.

- Humans can be deceived into giving reward in situations where they would otherwise not if they had more knowledge.

- Models will take advantage of this so they can get more reward.

- Models will therefore become deceptive.

Before continuing, I would encourage you to really engage with the above. Does it make sense to you? Is it making any hidden assumptions? Is it missing any steps? Can you rewrite it to be more mechanistically correct?

I believe that when people use the above threat model, they are either using it as shorthand for something else or they misunderstand how reinforcement learning works. Most alignment researchers will be in the former category. However, I was in the latter.

I was missing an important insight into how reinforcement learning setups are actually implemented. This lack of understanding led to lots of muddled thinking and general sloppiness on my part. I see others making the exact same mistake so I thought I would try and motivate a more careful use of language!

How Vanilla Reinforcement Learning Works

If I were to explain RL to my parents, I might say something like this:

- You want to train your dog to sit.

- You say "sit" and give your dog a biscuit if it sits.

- Your dog likes biscuits, and over time it will learn it can get more biscuits by sitting when told to do so.

- Biscuits have let you incentivise the behaviour you want.

- We do the same thing with a computer by giving the computer "reward" when it does things we like. Over time, the computer will do more of the behaviour we like so it can get more reward.

Do you agree with this? Is this analogy flawed in any way?

I claim this is actually NOT how vanilla reinforcement learning works.

The framing above views models as "wanting" reward, with reward being something models "receive" on taking certain actions. What actually happens is this:

- The model takes a series of actions (which we collect across multiple "episodes").

- After collecting these episodes, we determine how good the actions in each episode are using a reward function.

- We use gradient descent to alter the parameters of the model so the good actions will be more likely and the bad actions will be less likely when we next collect some episodes.

The insight is that the model itself never "gets" the reward. Reward is something used separately from the model/environment.

To motivate this, let's view the above process not from the vantage point of the overall training loop but from the perspective of the model itself. For the purposes of demonstration, let's assume the model is a conscious and coherent entity. From it's perspective, the above process looks like:

- Waking up with no memories in an environment.

- Taking a bunch of actions.

- Suddenly falling unconscious.

- Waking up with no memories in an environment.

- Taking a bunch of actions.

- and so on.....

The model never "sees" the reward. Each time it wakes up in an environment, its cognition has been altered slightly such that it is more likely to take certain actions than it was before.

Reward is the mechanism by which we select parameters, it is not something "given" to the model.

To (rather gruesomely) link this back to the dog analogy, RL is more like asking 100 dogs to sit, breeding the dogs which do sit and killing those which don't. Overtime, you will have a dog that can sit on command. No dog ever gets given a biscuit.

The phrasing I find most clear is this: Reinforcement learning should be viewed through the lens of selection, not the lens of incentivisation.

Why Does This Matter?

The "selection lens" has shifted my alignment intuitions a fair bit.

Goal-Directedness

It has changed how I think about goal-directed systems. I had unconsciously assumed models were strongly goal-directed by default and would do whatever they could to get more reward.

It's now clearer that goal-directedness in models is not a certainty, but something that can be potentially induced by the training process. If a model is goal-directed with respect to some goal, it is because such goal-directed cognition was selected for. Furthermore, it should be obvious that any learned goal will not be "get more reward", but something else. The model doesn't even see the reward!

CoinRun

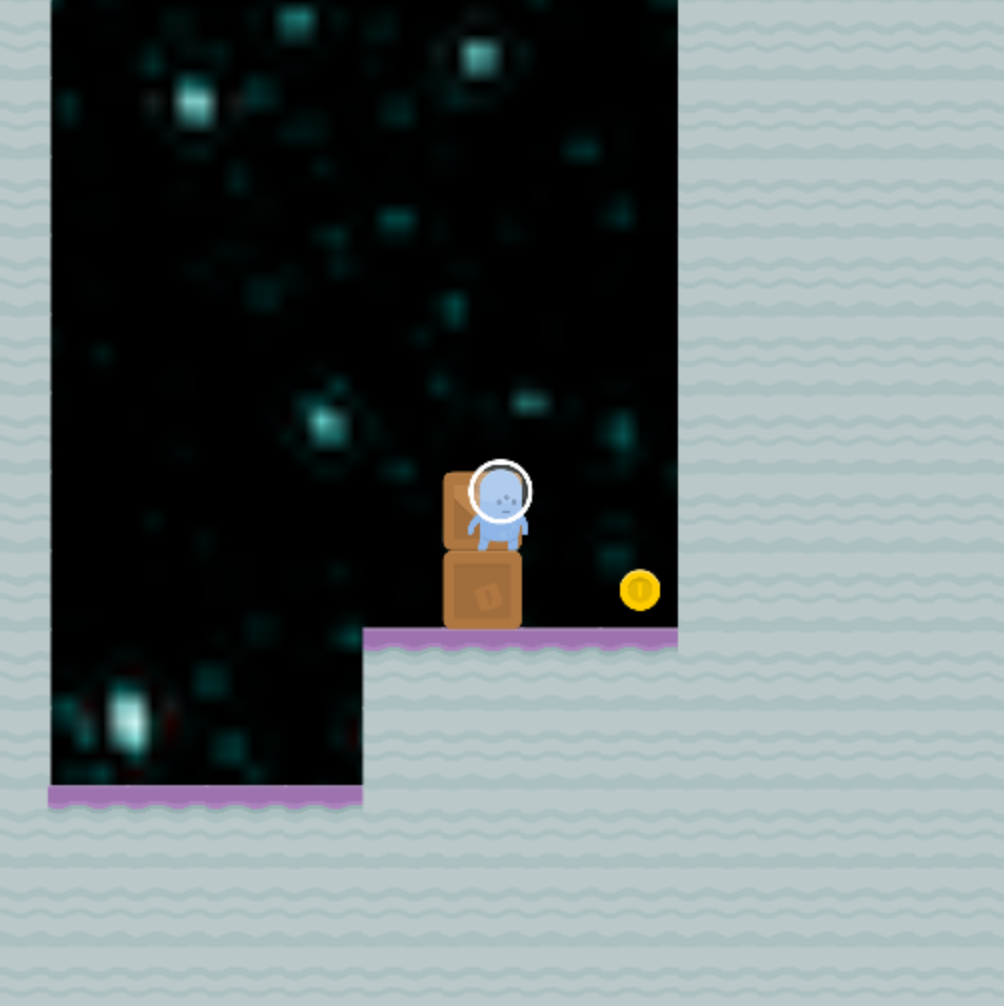

Langosco et al. found an interesting failure mode in CoinRun.

The set up is this:

- Have an agent navigate environments with a coin always on the right-hand side.

- Reward the model when it reaches the coin.

At train-time everything goes as you would expect. The agent will move to the right-hand side of the level and reach the coin.

However, if at test-time you move the coin so it is now on the left-hand side of the level, the agent will not navigate to the coin, but instead continue navigating to the right-hand side of the level.

When I first saw this result, my initial response was one of confusion before giving way to "Inner misalignment is real. We are in trouble."

Under the "reward as incentivization" framing, my rationalisation of the CoinRun behaviour was:

- At train-time, the model "wants" to get the coin.

- However, when we shift distribution at test-time, the model now "wants" to move to the right-hand side of the level.

(In hindsight, there were several things wrong with my thinking...)

Under the "reward as selection" framing, I find the behaviour much less confusing:

- We use reward to select for actions that led to the agent reaching the coin.

- This selects for models implementing the algorithm "move towards the coin".

- However, it also selects for models implementing the algorithm "always move to the right".

- It should therefore not be surprising you can end up with an agent that always moves to the right and not necessarily towards the coin.

Rewriting the Threat Model

Let's take another look at the simplified deception/RLHF threat model:

- A model takes some actions.

- If a human approves of these actions, the human gives the model some reward.

- Humans can be deceived into giving reward in situations where they would otherwise not if they had more knowledge.

- Models will take advantage of this so they can get more reward.

- Models will therefore become deceptive.

This assumes that models "want" reward, which isn't true. I think this threat model is confounding two related but different failure cases, which I would rewrite as the following:

1. Selecting For Bad Behaviour

- A model takes some actions.

- A human assigns positive reward to actions they approve of.

- RL makes such actions more likely in the future.

- Humans may assign reward to behaviour where they would not if they had more knowledge.

- RL will reinforce such behaviour.

- RLHF can therefore induce cognition in models which is unintended and "reflectively unwanted".

2. Induced Goal-Directedness

- Consider a hypothetical model that chooses actions by optimizing towards some internal goal which is highly correlated with the reward that would be assigned by a human overseer.

- Obviously, RL is going to exhibit selection pressure towards such a model.

- RLHF could then induce goal-directed cognition.

- This model does now indeed "want" to score highly according to some internal metric.

- One way of doing so is to be deceptive... etc etc

So failure cases such as deception are still very much possible, but I would guess a fair few people are confused about the concrete mechanisms by which deception can be brought about. I think this does meaningfully change how you should think about alignment. For instance, on rereading Ajeya Cotra's writing on situational awareness, I have gone from thinking that "playing the training game" is a certainty to something that could happen, but only after training somehow induces goal-directedness in the model.

One Final Exercise For the Reader

When reading about alignment, I now notice myself checking the following:

- Does the author ever refer to a model "being rewarded"?

- Does the author ever refer to a model taking action to "get reward"?

- If either of the above is true, can you rephrase their argument in terms of selection?

- Can you go further and rephrase the argument by completely tabooing the word "reward"?

- Does this exercise make the argument more or less compelling?

I have found going through the above to be a useful intuition-building exercise. Hopefully that will be the same for others!

I was talking through this with an AGI Safety group today, and while I think the selection lens is helpful and helps illustrate your point, I don't think the analogy quoted above is accurate in the way it should be.

The analogy you give is very similar to genetic algorithms, where models that get high reward are blended together with the other models that also get high reward and then mutated randomly. The only process that pushes performance to be better is that blending and mutating, which doesn't require any knowledge of how to improve the models' performance.

In other words, carrying out the breeding process requires no knowledge about what will make the dog more likely to sit. You just breed the ones that do sit. In essence, not even the breeder "gets the connection between the dogs' genetics and sitting".

However, at the start of your article, you describe gradient descent, which requires knowledge about how to get the models to perform better at the task. You need the gradient (the relationship between model parameters and reward at the level of tiny shifts to the model parameters) in order to perform gradient descent.

In gradient descent, just like the genetic algorithms, the model doesn't get access to the gradient or information about the reward. But you still need to know the relationship between behavior and reward in order to do the update. In essence, the model trainer "gets the connection between the models' parameters and performance".

So I think a revised version of the dog analogy that takes this connection information into account might be something more like:

1. Asking a single dog to sit, and monitoring its brain activity during and afterwards.

2. Search for dogs that have brain structures that you think would lead to them sitting, based on what you observed in the first dog's brain.

3. Ask one of those dogs to sit and monitor its brain activity.

4. Based on what you find, search for a better brain structure for sitting, etc.

At the end, you'll have likely found a dog that sits when you ask it to.

A more violent version would be:

1. Ask a single dog to sit and monitor brain activity

2. Kill the dog and modify its brain in a way you think would make it more likely to sit. Also remove all memories of its past life. (This is equivalent to trying to find a dog with a brain that's more conducive to sitting.)

3. Reinsert the new brain into the dog, ask it to sit again, and monitor its brain activity.

4. Repeat the process until the dog sits consistently.

To reiterate, with your breeding analogy, the person doing the breeding doesn't need to know anything about how the dogs' brains relate to sitting. They just breed them and hope for the best, just like in genetic algorithms. However, with this brain modification analogy, you do need to know how the dog's brain relates to sitting. You modify the brain in a way that you think will make it better, just like in gradient descent.

I'm not 100% sure why I think that this is an important distinction, but I do, so I figured I'd share it, in hopes of making the analogy less wrong.