While Dyson's birds and frogs archetypes of mathematicians is oft-mentioned, David Mumford's tribes of mathematicians is underappreciated, and I find myself pointing to it often in discussions that devolve into "my preferred kind of math research is better than yours"-type aesthetic arguments:

... the subjective nature and attendant excitement during mathematical activity, including a sense of its beauty, varies greatly from mathematician to mathematician... I think one can make a case for dividing mathematicians into several tribes depending on what most strongly drives them into their esoteric world. I like to call these tribes explorers, alchemists, wrestlers and detectives. Of course, many mathematicians move between tribes and some results are not cleanly part the property of one tribe.

- Explorers are people who ask -- are there objects with such and such properties and if so, how many? They feel they are discovering what lies in some distant mathematical continent and, by dint of pure thought, shining a light and reporting back what lies out there. The most beautiful things for them are the wholly new objects that they discover (the phrase 'bright shiny objects' has been in vogue recently) and these are especially sought by a sub-tribe that I call Gem Collectors. Explorers have another sub-tribe that I call Mappers who want to describe these new continents by making some sort of map as opposed to a simple list of 'sehenswürdigkeiten'.

- Alchemists, on the other hand, are those whose greatest excitement comes from finding connections between two areas of math that no one had previously seen as having anything to do with each other. This is like pouring the contents of one flask into another and -- something amazing occurs, like an explosion!

- Wrestlers are those who are focussed on relative sizes and strengths of this or that object. They thrive not on equalities between numbers but on inequalities, what quantity can be estimated or bounded by what other quantity, and on asymptotic estimates of size or rate of growth. This tribe consists chiefly of analysts and integrals that measure the size of functions but people in every field get drawn in.

- Finally Detectives are those who doggedly pursue the most difficult, deep questions, seeking clues here and there, sure there is a trail somewhere, often searching for years or decades. These too have a sub-tribe that I call Strip Miners: these mathematicians are convinced that underneath the visible superficial layer, there is a whole hidden layer and that the superficial layer must be stripped off to solve the problem. The hidden layer is typically more abstract, not unlike the 'deep structure' pursued by syntactical linguists. Another sub-tribe are the Baptizers, people who name something new, making explicit a key object that has often been implicit earlier but whose significance is clearly seen only when it is formally defined and given a name.

Mumford's examples of each, both results and mathematicians:

- Explorers:

- Theaetetus (ncient Greek list of the five Platonic solids)

- Ludwig Schläfli (extended the Greek list to regular polytopes in n dimensions)

- Bill Thurston ("I never met anyone with anything close to his skill in visualization")

- the list of finite simple groups

- Michael Artin (discovered non-commutative rings "lying in the middle ground between the almost commutative area and the truly huge free rings")

- Set theorists ("exploring that most peculiar, almost theological world of 'higher infinities'")

- Mappers:

- Mumford himself

- arguably, the earliest mathematicians (the story told by cuneiform surveying tablets)

- the Mandelbrot set

- Ramanujan's "integer expressible two ways as a sum of two cubes"

- the Concinnitas project of Bob Feldman and Dan Rockmore of ten aquatints

- Alchemists:

- Abraham De Moivre

- Oscar Zariski, Mumford's PhD advisor ("his deepest work was showing how the tools of commutative algebra, that had been developed by straight algebraists, had major geometric meaning and could be used to solve some of the most vexing issues of the Italian school of algebraic geometry")

- the Riemann-Roch theorem ("it was from the beginning a link between complex analysis and the geometry of algebraic curves. It was extended by pure algebra to characteristic p, then generalized to higher dimensions by Fritz Hirzebruch using the latest tools of algebraic topology. Then Michael Atiyah and Isadore Singer linked it to general systems of elliptic partial differential equations, thus connecting analysis, topology and geometry at one fell swoop")

- Wrestlers:

- Archimedes ("he loved estimating π and concocting gigantic numbers")

- Calculus ("stems from the work of Newton and Leibniz and in Leibniz's approach depends on distinguishing the size of infinitesimals from the size of their squares which are infinitely smaller")

- Euler's strange infinite series formulas

- Stirling's formula for the approximate size of n!

- Augustin-Louis Cauchy ("his eponymous inequality remains the single most important inequality in math")

- Sergei Sobolev

- Shing-Tung Yau

- Detectives:

- Andrew Wiles is probably the archetypal example

- Roger Penrose (""My own way of thinking is to ponder long and, I hope, deeply on problems and for a long time ... and I never really let them go.")

- Strip Miners:

- Alexander Grothendieck ("he greatest contemporary practitioner of this philosophy in the 20th century... Of all the mathematicians that I have met, he was the one whom I would unreservedly call a "genius". ... He considered that the real work in solving a mathematical problem was to find le niveau juste in which one finds the right statement of the problem at its proper level of generality. And indeed, his radical abstractions of schemes, functors, K-groups, etc. proved their worth by solving a raft of old problems and transforming the whole face of algebraic geometry)

- Leonard Euler from Switzerland and Carl Fredrich Gauss ("both showed how two dimensional geometry lay behind the algebra of complex numbers")

- Eudoxus and his spiritual successor Archimedes ("he level they reached was essentially that of a rigorous theory of real numbers with which they are able to calculate many specific integrals. Book V in Euclid's Elements and Archimedes The Method of Mechanical Theorems testify to how deeply they dug")

- Aryabhata

Some miscellaneous humorous quotes:

When I was teaching algebraic geometry at Harvard, we used to think of the NYU Courant Institute analysts as the macho guys on the scene, all wrestlers. I have heard that conversely they used the phrase 'French pastry' to describe the abstract approach that had leapt the Atlantic from Paris to Harvard.

Besides the Courant crowd, Shing-Tung Yau is the most amazing wrestler I have talked to. At one time, he showed me a quick derivation of inequalities I had sweated blood over and has told me that mastering this skill was one of the big steps in his graduate education. Its crucial to realize that outside pure math, inequalities are central in economics, computer science, statistics, game theory, and operations research. Perhaps the obsession with equalities is an aberration unique to pure math while most of the real world runs on inequalities.

In many ways [the Detective approach to mathematical research exemplified by e.g. Andrew Wiles] is the public's standard idea of what a mathematician does: seek clues, pursue a trail, often hitting dead ends, all in pursuit of a proof of the big theorem. But I think it's more correct to say this is one way of doing math, one style. Many are leery of getting trapped in a quest that they may never fulfill.

Scott Alexander's Mistakes, Dan Luu's Major errors on this blog (and their corrections), Gwern's My Mistakes (last updated 11 years ago), and Nintil's Mistakes (h/t @Rasool) are the only online writers I know of who maintain a dedicated, centralized page solely for cataloging their errors, which I admire. Probably not coincidentally they're also among the thinkers I respect the most for repeatedly empirically grounding their reasoning. Some orgs do this too, like 80K's Our mistakes, CEA's Mistakes we've made, and GiveWell's Our mistakes.

While I prefer dedicated centralized pages like those to one-off writeups for long content benefit reasons, one-off definitely beats none (myself included). In that regard I appreciate essays like Holden Karnofsky's Some Key Ways in Which I've Changed My Mind Over the Last Several Years (2016), Denise Melchin's My mistakes on the path to impact (2020), Zach Groff's Things I've Changed My Mind on This Year (2017), and this 2013 LW repository for "major, life-altering mistakes that you or others have made", as well as by orgs like HLI's Learning from our mistakes.

In this vein I'm also sad to see mistakes pages get removed, e.g. ACE used to have a Mistakes page (archived link) but now no longer do.

I'm not convinced Scott Alexander's mistakes page accurately tracks his mistakes. E.g. the mistake on it I know the most about is this one:

56: (5/27/23) In Raise Your Threshold For Accusing People Of Faking Bisexuality, I cited a study finding that most men’s genital arousal tracked their stated sexual orientation (ie straight men were aroused by women, gay men were aroused by men, bi men were aroused by either), but women’s genital arousal seemed to follow a bisexual pattern regardless of what orientation they thought they were - and concluded that although men’s orientation seemed hard-coded, women’s orientation must be more psychological. But Ozy cites a followup study showing that women (though not men) also show genital arousal in response to chimps having sex, suggesting women’s genital arousal doesn’t track actual attraction and is just some sort of mechanical process triggered by sexual stimuli. I should not have interpreted the results of genital arousal studies as necessarily implying attraction.

But that's basically wrong. The study found women's arousal to chimps having sex to be very close to their arousal to nonsexual stimuli, and far below their arousal to sexual stimuli.

I don't have a mistakes page but last year I wrote a one-off post of things I've changed my mind on.

I chose to study physics in undergrad because I wanted to "understand the universe" and naively thought string theory was the logically correct endpoint of this pursuit, and was only saved from that fate by not being smart enough to get into a good grad school. Since then I've come to conclude that string theory is probably a dead end, albeit an astonishingly alluring one for a particular type of person. In that regard I find anecdotes like the following by Ron Maimon on Physics SE interesting — the reason string theorists believe isn’t the same as what they tell people, so it’s better to ask for their conversion stories:

I think that it is better to ask for a compelling argument that the physics of gravity requires a string theory completion, rather than a mathematical proof, which would be full of implicit assumptions anyway. The arguments people give in the literature are not the same as the personal reasons that they believe the theory, they are usually just stories made up to sound persuasive to students or to the general public. They fall apart under scrutiny. The real reasons take the form of a conversion story, and are much more subjective, and much less persuasive to everyone except the story teller. Still, I think that a conversion story is the only honest way to explain why you believe something that is not conclusively experimentally established.

Some famous conversion stories are:

- Scherk and Schwarz (1974): They believed that the S-matrix bootstrap was a fundamental law of physics, and were persuaded that the bootstrap had a solution when they constructed proto-superstrings. An S-matrix theory doesn't really leave room for adding new interactions, as became clear in the early seventies with the stringent string consistency conditions, so if it were a fundamental theory of strong interactions only, how would you couple it to electromagnetism or to gravity? The only way is if gravitons and photons show up as certain string modes. Scherk understood how string theory reproduces field theory, so they understood that open strings easily give gauge fields. When they and Yoneya understood that the theory requires a perturbative graviton, they realized that it couldn't possibly be a theory of hadrons, but must include all interactions, and gravitational compactification gives meaning to the extra dimensions. Thankfully they realized this in 1974, just before S-matrix theory was banished from physics.

- Ed Witten (1984): At Princeton in 1984, and everywhere along the East Coast, the Chew bootstrap was as taboo as cold fusion. The bootstrap was tautological new-agey content-free Berkeley physics, and it was justifiably dead. But once Ed Witten understood that string theory cancels gravitational anomalies, this was sufficient to convince him that it was viable. He was aware that supergravity couldn't get chiral matter on a smooth compactification, and had a hard time fitting good grand-unification groups. Anomaly cancellation is a nontrivial constraint, it means that the theory works consistently in gravitational instantons, and it is hard to imagine a reason it should do that unless it is nonperturbatively consistent.

- Everyone else (1985): once they saw Ed Witten was on board, they decided it must be right.

I am exaggerating of course. The discovery of heterotic strings and Calabi Yau compactifications was important in convincing other people that string theory was phenomenologically viable, which was important. In the Soviet Union, I am pretty sure that Knizhnik believed string theory was the theory of everything, for some deep unknown reasons, although his collaborators weren't so sure. Polyakov liked strings because the link between the duality condition and the associativity of the OPE, which he and Kadanoff had shown should be enough to determines critical exponents in phase transitions, but I don't think he ever fully got on board with the "theory of everything" bandwagon.

The rest of Ron's answer elaborates on his own conversion story. The interesting part to me is that Ron began by trying to "kill string theory", and in fact he was very happy that he was going to do so, but then was annoyed by an argument of his colleague that mathematically worked, and in the year or two he spent puzzling over why it worked he had an epiphany that convinced him string theory was correct, which sounds like nonsense to the uninitiated. (This phenomenon where people who gain understanding of the thing become incomprehensible to others sounds a lot like the discussions on LW on enlightenment by the way.)

In pure math, mathematicians seek "morality", which sounds similar to Ron's string theory conversion stories above. Eugenia Cheng's Mathematics, morally argues:

I claim that although proof is what supposedly establishes the undeniable truth of a piece of mathematics, proof doesn’t actually convince mathematicians of that truth. And something else does.

... formal mathematical proofs may be wonderfully watertight, but they are impossible to understand. Which is why we don’t write whole formal mathematical proofs. ... Actually, when we write proofs what we have to do is convince the community that it could be turned into a formal proof. It is a highly sociological process, like appearing before a jury of twelve good men-and-true. The court, ultimately, cannot actually know if the accused actually ‘did it’ but that’s not the point; the point is to convince the jury. Like verdicts in court, our ‘sociological proofs’ can turn out to be wrong—errors are regularly found in published proofs that have been generally accepted as true. So much for mathematical proof being the source of our certainty. Mathematical proof in practice is certainly fallible.

But this isn’t the only reason that proof is unconvincing. We can read even a correct proof, and be completely convinced of the logical steps of the proof, but still not have any understanding of the whole. Like being led, step by step, through a dark forest, but having no idea of the overall route. We’ve all had the experience of reading a proof and thinking “Well, I see how each step follows from the previous one, but I don’t have a clue what’s going on!”

And yet... The mathematical community is very good at agreeing what’s true. And even if something

is accepted as true and then turns out to be untrue, people agree about that as well. Why? ...Mathematical theories rarely compete at the level of truth. We don’t sit around arguing about which theory is right and which is wrong. Theories compete at some other level, with questions about what the theory “ought” to look like, what the “right” way of doing it is. It’s this other level of ‘ought’ that we call morality. ... Mathematical morality is about how mathematics should behave, not just that this is right, this is wrong. Here are some examples of the sorts of sentences that involve the word “morally”, not actual

examples of moral things.“So, what’s actually going on here, morally?”

“Well, morally, this proof says...”

“Morally, this is true because...”

“Morally, there’s no reason for this axiom.”

“Morally, this question doesn’t make any sense.”

“What ought to happen here, morally?”

“This notation does work, but morally, it’s absurd!”

“Morally, this limit shouldn’t exist at all”

“Morally, there’s something higher-dimensional going on here.”Beauty/elegance is often the opposite of morality. An elegant proof is often a clever trick, a piece of magic as in Example 6 above, the sort of proof that drives you mad when you’re trying to understand something precisely because it’s so clever that it doesn’t explain anything at all.

Constructiveness is often the opposite of morality as well. If you’re proving the existence of something and you just construct it, you haven’t necessarily explained why the thing exists.

Morality doesn't mean 'explanatory' either. There are so many levels of explaining something. Explanatory to whom? To someone who’s interested in moral reasons. So we haven’t really got anywhere. The same goes for intuitive, obvious, useful, natural and clear, and as Thurston says: “one person’s clear mental image is another person’s intimidation”.

Minimality/efficiency is sometimes the opposite of morality too. Sometimes the most efficient way of proving something is actually the moral way backwards. eg quadratics. And the most minimal way of presenting a theory is not necessarily the morally right way. For example, it is possible to show that a group is a set X equipped with one binary operation / satisfying the single axiom for all x, y, z ∈ X, (x/((((x/x)/y)/z)/(((x/x)/x)/z))) = y. The fact that something works is not good enough to be a moral reason.

Polya’s notion of ‘plausible reasoning’ at first sight might seem to fit the bill because it appears to be about how mathematicians decide that something is ‘plausible’ before sitting down to try and prove it. But in fact it’s somewhat probabilistic. This is not the same as a moral reason. It’s more like gathering a lot of evidence and deciding that all the evidence points to one conclusion, without there actually being a reason necessarily. Like in court, having evidence but no motive.

Abstraction perhaps gets closer to morality, along with ‘general’, ‘deep’, ‘conceptual’. But I would say that it’s the search for morality that motivates abstraction, the search for the moral reason motivates the search for greater generalities, depth and conceptual understanding. ...

Proof has a sociological role; morality has a personal role. Proof is what convinces society; morality is what convinces us. Brouwer believed that a construction can never be perfectly communicated by verbal or symbolic language; rather it’s a process within the mind of an individual mathematician. What we write down is merely a language for communicating something to other mathematicians, in the hope that they will be able to reconstruct the process within their own mind. When I’m doing maths I often feel like I have to do it twice—once, morally in my head. And then once to translate it into communicable form. The translation is not a trivial process; I am going to encapsulate it as the process of moving from one form of truth to another.

Transmitting beliefs directly is unfeasible, but the question that does leap out of this is: what about the reason? Why don’t I just send the reason directly to X, thus eliminating the two probably hardest parts of this process? The answer is that a moral reason is harder to communicate than a proof. The key characteristic about proof is not its infallibility, not its ability to convince but its transferability. Proof is the best medium for communicating my argument to X in a way which will not be in danger of ambiguity, misunderstanding, or defeat. Proof is the pivot for getting from one person to another, but some translation is needed on both sides. So when I read an article, I always hope that the author will have included a reason and not just a proof, in case I can convince myself of the result without having to go to all the trouble of reading the fiddly proof.

That last part is quite reminiscent of what the late Bill Thurston argued in his classic On proof and progress in mathematics:

Mathematicians have developed habits of communication that are often dysfunctional. Organizers of colloquium talks everywhere exhort speakers to explain things in elementary terms. Nonetheless, most of the audience at an average colloquium talk gets little of value from it. Perhaps they are lost within the first 5 minutes, yet sit silently through the remaining 55 minutes. Or perhaps they quickly lose interest because the speaker plunges into technical details without presenting any reason to investigate them. At the end of the talk, the few mathematicians who are close to the field of the speaker ask a question or two to avoid embarrassment.

This pattern is similar to what often holds in classrooms, where we go through the motions of saying for the record what we think the students “ought” to learn, while the students are trying to grapple with the more fundamental issues of learning our language and guessing at our mental models. Books compensate by giving samples of how to solve every type of homework problem. Professors compensate by giving homework and tests that are much easier than the material “covered” in the course, and then grading the homework and tests on a scale that requires little understanding. We assume that the problem is with the students rather than with communication: that the students either just don’t have what it takes, or else just don’t care.

Outsiders are amazed at this phenomenon, but within the mathematical community, we dismiss it with shrugs.

Much of the difficulty has to do with the language and culture of mathematics, which is divided into subfields. Basic concepts used every day within one subfield are often foreign to another subfield. Mathematicians give up on trying to understand the basic concepts even from neighboring subfields, unless they were clued in as graduate students.

In contrast, communication works very well within the subfields of mathematics. Within a subfield, people develop a body of common knowledge and known techniques. By informal contact, people learn to understand and copy each other’s ways of thinking, so that ideas can be explained clearly and easily.

Mathematical knowledge can be transmitted amazingly fast within a subfield. When a significant theorem is proved, it often (but not always) happens that the solution can be communicated in a matter of minutes from one person to another within the subfield. The same proof would be communicated and generally understood in an hour talk to members of the subfield. It would be the subject of a 15- or 20-page paper, which could be read and understood in a few hours or perhaps days by members of the subfield.

Why is there such a big expansion from the informal discussion to the talk to the paper? One-on-one, people use wide channels of communication that go far beyond formal mathematical language. They use gestures, they draw pictures and diagrams, they make sound effects and use body language. Communication is more likely to be two-way, so that people can concentrate on what needs the most attention. With these channels of communication, they are in a much better position to convey what’s going on, not just in their logical and linguistic facilities, but in their other mental facilities as well.

In talks, people are more inhibited and more formal. Mathematical audiences are often not very good at asking the questions that are on most people’s minds, and speakers often have an unrealistic preset outline that inhibits them from addressing questions even when they are asked.

In papers, people are still more formal. Writers translate their ideas into symbols and logic, and readers try to translate back.

Why is there such a discrepancy between communication within a subfield and communication outside of subfields, not to mention communication outside mathematics? Mathematics in some sense has a common language: a language of symbols, technical definitions, computations, and logic. This language efficiently conveys some, but not all, modes of mathematical thinking. Mathematicians learn to translate certain things almost unconsciously from one mental mode to the other, so that some statements quickly become clear. Different mathematicians study papers in different ways, but when I read a mathematical paper in a field in which I’m conversant, I concentrate on the thoughts that are between the lines. I might look over several paragraphs or strings of equations and think to myself “Oh yeah, they’re putting in enough rigamarole to carry such-and-such idea.” When the idea is clear, the formal setup is usually unnecessary and redundant—I often feel that I could write it out myself more easily than figuring out what the authors actually wrote. It’s like a new toaster that comes with a 16-page manual. If you already understand toasters and if the toaster looks like previous toasters you’ve encountered, you might just plug it in and see if it works, rather than first reading all the details in the manual.

People familiar with ways of doing things in a subfield recognize various patterns of statements or formulas as idioms or circumlocution for certain concepts or mental images. But to people not already familiar with what’s going on the same patterns are not very illuminating; they are often even misleading. The language is not alive except to those who use it.

Thurston's personal reflections below on the sociology of proof exemplify the search for mathematical morality instead of fully formally rigorous correctness. I remember being disquieted upon first reading "There were published theorems that were generally known to be false" a long time ago:

When I started as a graduate student at Berkeley, I had trouble imagining how I could “prove” a new and interesting mathematical theorem. I didn’t really understand what a “proof” was.

By going to seminars, reading papers, and talking to other graduate students, I gradually began to catch on. Within any field, there are certain theorems and certain techniques that are generally known and generally accepted. When you write a paper, you refer to these without proof. You look at other papers in the field, and you see what facts they quote without proof, and what they cite in their bibliography. You learn from other people some idea of the proofs. Then you’re free to quote the same theorem and cite the same citations. You don’t necessarily have to read the full papers or books that are in your bibliography. Many of the things that are generally known are things for which there may be no known written source. As long as people in the field are comfortable that the idea works, it doesn’t need to have a formal written source.

At first I was highly suspicious of this process. I would doubt whether a certain idea was really established. But I found that I could ask people, and they could produce explanations and proofs, or else refer me to other people or to written sources that would give explanations and proofs. There were published theorems that were generally known to be false, or where the proofs were generally known to be incomplete. Mathematical knowledge and understanding were embedded in the minds and in the social fabric of the community of people thinking about a particular topic. This knowledge was supported by written documents, but the written documents were not really primary.

I think this pattern varies quite a bit from field to field. I was interested in geometric areas of mathematics, where it is often pretty hard to have a document that reflects well the way people actually think. In more algebraic or symbolic fields, this is not necessarily so, and I have the impression that in some areas documents are much closer to carrying the life of the field. But in any field, there is a strong social standard of validity and truth. Andrew Wiles’s proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem is a good illustration of this, in a field which is very algebraic. The experts quickly came to believe that his proof was basically correct on the basis of high-level ideas, long before details could be checked. This proof will receive a great deal of scrutiny and checking compared to most mathematical proofs; but no matter how the process of verification plays out, it helps illustrate how mathematics evolves by rather organic psychological and social processes.

Since then I've come to conclude that string theory is probably a dead end, albeit an astonishingly alluring one for a particular type of person.

The more you know about particle physics and quantum field theory, the more inevitable string theory seems. There are just too many connections. However, identifying the specific form of string theory that corresponds to our universe is more of a challenge, and not just because of the fabled 10^500 vacua (though it could be one of those). We don't actually know either all the possible forms of string theory, or the right way to think about the physics that we can see. The LHC, with its "unnaturally" light Higgs boson, already mortally wounded a particular paradigm for particle physics (naturalness) which in turn was guiding string phenomenology (i.e. the part of string theory that tries to be empirically relevant). So along with the numerical problem of being able to calculate the properties of a given string vacuum, the conceptual side of string theory and string phenomenology is still wide open for discovery.

I asked a well-known string theorist about the fabled 10^500 vacua and asked him whether he worried that this would make string theory a vacuous theory since a theory that fits anything fits nothing. He replied ' no, no the 10^500 'swampland' is a great achievement of string theory - you see... all other theories have infinitely many adjustable parameters'. He was saying string theory was about ~1500 bits away from the theory of everything but infinitely ahead of its competitors.

Diabolical.

Much ink has been spilled on the scientific merits and demerits of string theory and its competitors. The educated reader will recognize that this all this and more is of course, once again, solved by UDASSA.

Re other theories, I don't think that all other theories in existence have infinitely many adjustable parameters, and if he's referring to the fact that lots of theories have adjustable parameters that can range over the real numbers, which are infinitely complicated in general, than that's different, and string theory may have this issue as well.

Re string theory's issue of being vacuous, I think the core thing that string theory predicts that other quantum gravity models don't is that at the large scale, you recover general relativity and the standard model, whereas no other theory can yet figure out a way to properly include both the empirical effects of gravity and quantum mechanics in the parameter regimes where they are known to work, so string theory predicts more just by predicting the things other quantum mechanics predicts while having the ability to include in gravity without ruining the other predictions, whereas other models of quantum gravity tend to ruin empirical predictions like general relativity approximately holding pretty fast.

I used to consider it a mystery that math was so unreasonably effective in the natural sciences, but changed my mind after reading this essay by Eric S. Raymond (who's here on the forum, hi and thanks Eric), in particular this part, which is as good a question dissolution as any I've seen:

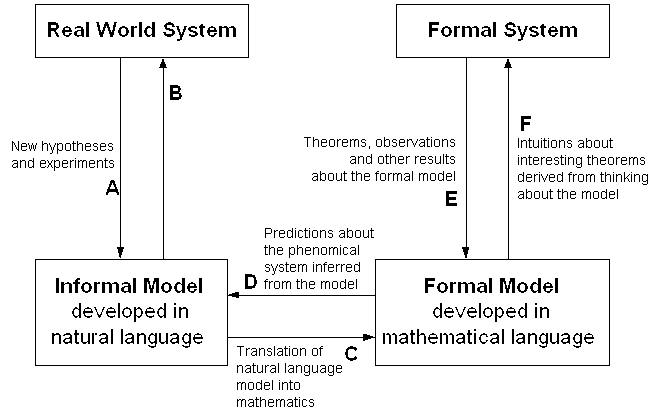

The relationship between mathematical models and phenomenal prediction is complicated, not just in practice but in principle. Much more complicated because, as we now know, there are mutually exclusive ways to axiomatize mathematics! It can be diagrammed as follows (thanks to Jesse Perry for supplying the original of this chart):

(it's a shame this chart isn't rendering properly for some reason, since without it the rest of Eric's quote is ~incomprehensible)

The key transactions for our purposes are C and D -- the translations between a predictive model and a mathematical formalism. What mystified Einstein is how often D leads to new insights.

We begin to get some handle on the problem if we phrase it more precisely; that is, "Why does a good choice of C so often yield new knowledge via D?"

The simplest answer is to invert the question and treat it as a definition. A "good choice of C" is one which leads to new predictions. The choice of C is not one that can be made a-priori; one has to choose, empirically, a mapping between real and mathematical objects, then evaluate that mapping by seeing if it predicts well.

One can argue that it only makes sense to marvel at the utility of mathematics if one assumes that C for any phenomenal system is an a-priori given. But we've seen that it is not. A physicist who marvels at the applicability of mathematics has forgotten or ignored the complexity of C; he is really being puzzled at the human ability to choose appropriate mathematical models empirically.

By reformulating the question this way, we've slain half the dragon. Human beings are clever, persistent apes who like to play with ideas. If a mathematical formalism can be found to fit a phenomenal system, some human will eventually find it. And the discovery will come to look "inevitable" because those who tried and failed will generally be forgotten.

But there is a deeper question behind this: why do good choices of mathematical model exist at all? That is, why is there any mathematical formalism for, say, quantum mechanics which is so productive that it actually predicts the discovery of observable new particles?

The way to "answer" this question is by observing that it, too, properly serves as a kind of definition. There are many phenomenal systems for which no such exact predictive formalism has been found, nor for which one seems likely. Poets like to mumble about the human heart, but more mundane examples are available. The weather, or the behavior of any economy larger than village size, for example -- systems so chaotically interdependent that exact prediction is effectively impossible (not just in fact but in principle).

There are many things for which mathematical modeling leads at best to fuzzy, contingent, statistical results and never successfully predicts 'new entities' at all. In fact, such systems are the rule, not the exception. So the proper answer to the question "Why is mathematics is so marvelously applicable to my science?" is simply "Because that's the kind of science you've chosen to study!"

I also think I was intuition-pumped to buy Eric's argument by Julie Moronuki's beautiful meandering essay The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Metaphor.

Interesting. This reminds me of a related thought I had: Why do models with differential equations work so often in physics but so rarely in other empirical sciences? Perhaps physics simply is "the differential equation science".

Which is also related to the frequently expressed opinion that philosophy makes little progress because everything that gets developed enough to make significant progress splits off from philosophy. Because philosophy is "the study of ill-defined and intractable problems".

Not saying that I think these views are accurate, though they do have some plausibility.

The weather, or the behavior of any economy larger than village size, for example -- systems so chaotically interdependent that exact prediction is effectively impossible (not just in fact but in principle).

Flagging that those two examples seem false. The weather is chaotic, yes, and there's a sense in which the economy is anti-inductive, but modeling methods are advancing, and will likely find more loop-holes in chaos theory.

For example, in thermodynamics, temperature is non-chaotic while the precise kinetic energies and locations of all particles are. A reasonable candidate similarity in weather are hurricanes.

Similarly as our understanding of the economy advances it will get more efficient which means it will be easier to model. eg (note: I've only skimmed this paper). And definitely large economies are even more predictable than small villages, talk about not having a competitive market!

Thanks for the pointer to that paper, the abstract makes me think there's a sort of slow-acting self-reinforcing feedback loop between predictive error minimisation via improving modelling and via improving the economy itself.

re: weather, I'm thinking of the chart below showing how little gain we get in MAE vs compute, plus my guess that compute can't keep growing far enough to get MAE < 3 °F a year out (say). I don't know anything about advancements in weather modelling methods though; maybe effective compute (incorporating modelling advancements) may grow indefinitely in terms of the chart.

I didn't say anything about temperature prediction, and I'd also like to see any other method (intuition based or otherwise) do better than the current best mathematical models here. It seems unlikely to me that the trends in that graph will continue arbitrarily far.

Thanks for the pointer to that paper, the abstract makes me think there's a sort of slow-acting self-reinforcing feedback loop between predictive error minimisation via improving modelling and via improving the economy itself.

Yeah, that was my claim.

I would also comment that, if the environment was so chaotic that roughly everything important to life could not be modeled—if general-purpose modeling ability was basically useless—then life would not have evolved that ability, and "intelligent life" probably wouldn't exist.

The two concepts that I thought were missing from Eliezer's technical explanation of technical explanation that would have simplified some of the explanation were compression and degrees of freedom. Degrees of freedom seems very relevant here in terms of how we map between different representations. Why are representations so important for humans? Because they have different computational properties/traversal costs while humans are very computationally limited.

Can you say more about what you mean? Your comment reminded me of Thomas Griffiths' paper Understanding Human Intelligence through Human Limitations, but you may have meant something else entirely.

Griffiths argued that the aspects we associate with human intelligence – rapid learning from small data, the ability to break down problems into parts, and the capacity for cumulative cultural evolution – arose from the 3 fundamental limitations all humans share: limited time, limited computation, and limited communication. (The constraints imposed by these characteristics cascade: limited time magnifies the effect of limited computation, and limited communication makes it harder to draw upon more computation.) In particular, limited computation leads to problem decomposition, hence modular solutions; relieving the computation constraint enables solutions that can be objectively better along some axis while also being incomprehensible to humans.

Thanks for the link. I mean that predictions are outputs of a process that includes a representation, so part of what's getting passed back and forth in the diagram are better and worse fit representations. The degrees of freedom point is that we choose very flexible representations, whittle them down with the actual data available, then get surprised that that representation yields other good predictions. But we should expect this if Nature shares any modular structure with our perception at all, which it would if there was both structural reasons (literally same substrate) and evolutionary pressure for representations with good computational properties i.e. simple isomorphisms and compressions.

Matt Leifer, who works in quantum foundations, espouses a view that's probably more extreme than Eric Raymond's above to argue why the effectiveness of math in the natural sciences isn't just reasonable but expected-by-construction. In his 2015 FQXi essay Mathematics is Physics Matt argued that

... mathematics is a natural science—just like physics, chemistry, or biology—and that this can explain the alleged “unreasonable” effectiveness of mathematics in the physical sciences.

The main challenge for this view is to explain how mathematical theories can become increasingly abstract and develop their own internal structure, whilst still maintaining an appropriate empirical tether that can explain their later use in physics. In order to address this, I offer a theory of mathematical theory-building based on the idea that human knowledge has the structure of a scale-free network and that abstract mathematical theories arise from a repeated process of replacing strong analogies with new hubs in this network.

This allows mathematics to be seen as the study of regularities, within regularities, within . . . , within regularities of the natural world. Since mathematical theories are derived from the natural world, albeit at a much higher level of abstraction than most other scientific theories, it should come as no surprise that they so often show up in physics.

... mathematical objects do not refer directly to things that exist in the physical universe. As the formalists suggest, mathematical theories are just abstract formal systems, but not all formal systems are mathematics. Instead, mathematical theories are those formal systems that maintain a tether to empirical reality through a process of abstraction and generalization from more empirically grounded theories, aimed at achieving a pragmatically useful representation of regularities that exist in nature.

(Matt notes as an aside that he's arguing for precisely the opposite of Tegmark's MUH.)

Why "scale-free network"?

It is common to view the structure of human knowledge as hierarchical... The various attempts to reduce all of mathematics to logic or arithmetic reflect a desire view mathematical knowledge as hanging hierarchically from a common foundation. However, the fact that mathematics now has multiple competing foundations, in terms of logic, set theory or category theory, indicates that something is wrong with this view.

Instead of a hierarchy, we are going to attempt to characterize the structure of human knowledge in terms of a network consisting of nodes with links between them... Roughly speaking, the nodes are

supposed to represent different fields of study. This could be done at various levels of detail. ... Next, a link should be drawn between two nodes if there is a strong connection between the things they represent. Again, I do not want to be too precise about what this connection should be, but examples would include an idea being part of a wider theory, that one thing can be derived from the other, or that there exists a strong direct analogy between the two nodes. Essentially, if it has occurred to a human being that the two things are strongly related, e.g. if it has been thought interesting enough to do something like publish an academic paper on the connection, and the connection has not yet been explained in terms of some intermediary theory, then there should be a link between the corresponding nodes in the network.If we imagine drawing this network for all of human knowledge then it is plausible that it would have

the structure of a scale-free network. Without going into technical details, scale-free networks have a small number of hubs, which are nodes that are linked to a much larger number of nodes than the average. This is a bit like the 1% of billionaires who are much richer than the rest of the human population. If the knowledge network is scale-free then this would explain why it seems so plausible that knowledge is hierarchical. In a university degree one typically learns a great deal about one of the hubs, e.g. the hub representing fundamental physics, and a little about some of the more specialized subjects that hang from it. As we get ever more specialized, we typically move away from our starting hub towards more obscure nodes, which are nonetheless still much closer to the starting hub than to any other hub. The local part of the network that we know about looks much like a hierarchy, and so it is not surprising that physicists end up thinking that everything boils down to physics whereas sociologists end up thinking that everything is a social construct. In reality, neither of these views is right because the global structure of the network is not a hierarchy.As a naturalist, I should provide empirical evidence that human knowledge is indeed structured as a scale-free network. The best evidence that I can offer is that the structure of pages and links on the Word Wide Web and the network of citations to academic papers are both scale free [13]. These are, at best, approximations of the true knowledge network. ... However, I think that these examples provide evidence that the information structures generated by a social network of finite beings are typically scale-free networks, and the knowledge network is an example of such a structure.

As an aside, Matt's theory of theory-building explains (so he claims) what mathematical intuition is about: "intuition for efficient knowledge structure, rather than intuition about an abstract mathematical world".

So what? How does this view pay rent?

Firstly, in network language, the concept of a “theory of everything” corresponds to a network with one enormous hub, from which all other human knowledge hangs via links that mean “can be derived from”. This represents a hierarchical view of knowledge, which seems unlikely to be true if the structure of human knowledge is generated by a social process. It is not impossible for a scale-free network to have a hierarchical structure like a branching tree, but it seems unlikely that the process of knowledge growth would lead uniquely to such a structure. It seems more likely that we will always have several competing large hubs and that some aspects of human experience, such as consciousness and why we experience a unique present moment of time, will be forever outside the scope of physics.

Nonetheless, my theory suggests that the project of finding higher level connections that encompass more of human knowledge is still a fruitful one. It prevents our network from having an unwieldy number of direct links, allows us to share more common vocabulary between fields, and allows an individual to understand more of the world with fewer theories. Thus, the search for a theory of everything is not fruitless; I just do not expect it to ever terminate.

Secondly, my theory predicts that the mathematical representation of fundamental physical theories will continue to become increasingly abstract. The more phenomena we try to encompass in our fundamental theories, the further the resulting hubs will be from the nodes representing our direct sensory experience. Thus, we should not expect future theories of physics to become less mathematical, as they are generated by the same process of generalization and abstraction as mathematics itself.

Matt further develops the argument that the structure of human knowledge being networked-not-hierarchical implies that the idea that there is a most fundamental discipline, or level of reality, is mistaken in Against Fundamentalism, another FQXi essay published in 2018.

What fraction of economically-valuable cognitive labor is already being automated today? How has that changed over time, especially recently?

I notice I'm confused about these ostensibly extremely basic questions, which arose in reading Open Phil's old CCF-takeoff report, whose main metric is "time from AI that could readily[2] automate 20% of cognitive tasks to AI that could readily automate 100% of cognitive tasks". A cursory search of Epoch's data, Metaculus, and this forum didn't turn up anything, but I didn't spend much time at all doing so.

I was originally motivated by wanting to empirically understand recursive AI self-improvement better, which led to me stumbling upon the CAIS paper Examples of AI Improving AI, but I don't have any sense whatsoever of how the paper's 39 examples as of Oct-2023 translate to OP's main metric even after constraining "cognitive tasks" in its operational definition to just AI R&D.

I did find this 2018 survey of expert opinion

A survey was administered to attendees of three AI conferences during the summer of 2018 (ICML, IJCAI and the HLAI conference). The survey included questions for estimating AI capabilities over the next decade, questions for forecasting five scenarios of transformative AI and questions concerning the impact of computational resources in AI research. Respondents indicated a median of 21.5% of human tasks (i.e., all tasks that humans are currently paid to do) can be feasibly automated now, and that this figure would rise to 40% in 5 years and 60% in 10 years

which would suggest that OP's clock should've started ticking in 2018, so that incorporating CCF-takeoff author Tom Davidson's "~50% to a <3 year takeoff and ~80% to <10 year i.e. time from 20%-AI to 100%-AI, for cognitive tasks in the global economy" means takeoff should've already occurred... so I'm dismissing this survey's relevance to my question (sorry).

What fraction of economically-valuable cognitive labor is already being automated today?

Did e.g. a telephone operator in 1910 perform cognitive labor, by the definition we want to use here?

I'm mainly wondering how Open Phil, and really anyone who uses fraction of economically-valuable cognitive labor automated / automatable (e.g. the respondents to that 2018 survey; some folks on the forum) as a useful proxy for thinking about takeoff, tracks this proxy as a way to empirically ground their takeoff-related reasoning. If you're one of them, I'm curious if you'd answer your own question in the affirmative?

I am not one of them - I was wondering the same thing, and was hoping you had a good answer.

If I was trying to answer this question, I would probably try to figure out what fraction of all economically-valuable labor each year was cognitive, the breakdown of which tasks comprise that labor, and the year-on-year productivity increases on those task, then use that to compute the percentage of economically-valuable labor that is being automated that year.

Concretely, to get a number for the US in 1900 I might use a weighted average of productivity increases across cognitive tasks in 1900, in an approach similar to how CPI is computed

- Look at the occupations listed in the 1900 census records

- Figure out which ones are common, and then sample some common ones and make wild guesses about what those jobs looked like in 1900

- Classify those tasks as cognitive or non-cognitive

- Come to estimate that record-keeping tasks are around a quarter to a half of all cognitive labor

- Notice that typewriters were starting to become more popular - about 100,000 typewriters sold per year

- Note that those 100k typewriters were going to the people who would save the most time by using them

- As such, estimate 1-2% productivity growth in record-keeping tasks in 1900

- Multiply the productivity growth for record-keeping tasks by the fraction of time (technically actually 1-1/productivity increase but when productivity increase is small it's not a major factor)

- Estimate that 0.5% of cognitive labor was automated by specifically typewriters in 1900

- Figure that's about half of all cognitive labor automation in 1900

and thus I would estimate ~1% of all cognitive labor was automated in 1900. By the same methodology I would probably estimate closer to 5% for 2024.

Again, though, I am not associated with Open Phil and am not sure if they think about cognitive task automation in the same way.

Unbundling Tools for Thought is an essay by Fernando Borretti I found via Gwern's comment which immediately resonated with me (emphasis mine):

I’ve written something like six or seven personal wikis over the past decade. It’s actually an incredibly advanced form of procrastination1. At this point I’ve tried every possible design choice.

Lifecycle: I’ve built a few compiler-style wikis: plain-text files in a

gitrepo statically compiled to HTML. I’ve built a couple using live servers with server-side rendering. The latest one is an API server with a React frontend.Storage: I started with plain text files in a git repo, then moved to an SQLite database with a simple schema. The latest version is an avant-garde object-oriented hypermedia database with bidirectional links implemented on top of SQLite.

Markup: I used Markdown here and there. Then I built my own TeX-inspired markup language. Then I tried XML, with mixed results. The latest version uses a WYSIWYG editor made with ProseMirror.

And yet I don’t use them. Why? Building them was fun, sure, but there must be utility to a personal database.

At first I thought the problem was friction: the higher the activation energy to using a tool, the less likely you are to use it. Even a small amount of friction can cause me to go, oh, who cares, can’t be bothered. So each version gets progressively more frictionless2. The latest version uses a WYSIWYG editor built on top of ProseMirror (it took a great deal for me to actually give in to WYSIWYG). It also has a link to the daily note page, to make journalling easier. The only friction is in clicking the bookmark to

localhost:5000. It is literally two clicks to get to the daily note.And yet I still don’t use it. Why? I’m a great deal more organized now than I was a few years ago. My filesystem is beautifully structured and everything is where it should be. I could fill out the contents of a personal wiki.

I’ve come to the conclusion that there’s no point: because everything I can do with a personal wiki I can do better with a specialized app, and the few remaining use cases are useless. Let’s break it down.

I've tried three different times to create a personal wiki, using the last one for a solid year and a half before finally giving up and just defaulting to a janky combination of Notion and Google Docs/Sheets, seduced by sites like Cosma Shalizi's and Gwern's long content philosophy (emphasis mine):

... I have read blogs for many years and most blog posts are the triumph of the hare over the tortoise. They are meant to be read by a few people on a weekday in 2004 and never again, and are quickly abandoned—and perhaps as Assange says, not a moment too soon. (But isn’t that sad? Isn’t it a terrible ROI for one’s time?) On the other hand, the best blogs always seem to be building something: they are rough drafts—works in progress15. So I did not wish to write a blog. Then what? More than just “evergreen content”, what would constitute Long Content as opposed to the existing culture of Short Content? How does one live in a Long Now sort of way?16

My answer is that one uses such a framework to work on projects that are too big to work on normally or too tedious. (Conscientiousness is often lacking online or in volunteer communities18 and many useful things go undone.) Knowing your site will survive for decades to come gives you the mental wherewithal to tackle long-term tasks like gathering information for years, and such persistence can be useful19—if one holds onto every glimmer of genius for years, then even the dullest person may look a bit like a genius himself20. (Even experienced professionals can only write at their peak for a few hours a day—usually first thing in the morning, it seems.) Half the challenge of fighting procrastination is the pain of starting—I find when I actually get into the swing of working on even dull tasks, it’s not so bad. So this suggests a solution: never start. Merely have perpetual drafts, which one tweaks from time to time. And the rest takes care of itself.

Fernando unbundles the use cases of a tool for thought in his essay; I'll just quote the part that resonated with me:

The following use cases are very naturally separable: ...

Learning: if you’re studying something, you can keep your notes in a TfT. This is one of the biggest use cases. But the problem is never note-taking, but reviewing notes. Over the years I’ve found that long-form lecture notes are all but useless, not just because you have to remember to review them on a schedule, but because spaced repetition can subsume every single lecture note. It takes practice and discipline to write good spaced repetition flashcards, but once you do, the long-form prose notes are themselves redundant.

(Tangentially, an interesting example of how comprehensively subsuming spaced repetition is is Michael Nielsen's Using spaced repetition systems to see through a piece of mathematics, in which he describes how he used "deep Ankification" to better understand the theorem that a complex normal matrix is always diagonalizable by a unitary matrix, as an illustration of a heuristic one could use to deepen one's understanding of a piece of mathematics in an open-ended way, inspired by Andrey Kolmogorov's essay on, of all things, the equals sign. I wish I read that while I was still studying physics in school.)

Fernando, emphasis mine:

So I often wonder: what do other people use their personal knowledge bases for? And I look up blog and forum posts where Obsidian and Roam power users explain their setup. And most of what I see is junk. It’s never the Zettelkasten of the next Vannevar Bush, it’s always a setup with tens of plugins, a daily note three pages long that is subdivided into fifty subpages recording all the inane minutiae of life. This is a recipe for burnout.

People have this aspirational idea of building a vast, oppressively colossal, deeply interlinked knowledge graph to the point that it almost mirrors every discrete concept and memory in their brain. And I get the appeal of maximalism. But they’re counting on the wrong side of the ledger. Every node in your knowledge graph is a debt. Every link doubly so. The more you have, the more in the red you are. Every node that has utility—an interesting excerpt from a book, a pithy quote, a poem, a fiction fragment, a few sentences that are the seed of a future essay, a list of links that are the launching-off point of a project—is drowned in an ocean of banality. Most of our thoughts appear and pass away instantly, for good reason.

Minimizing friction is surprisingly difficult. I keep plain-text notes in a hierarchical editor (cherrytree), but even that feels too complicated sometimes. This is not just about the tool... what you actually need is a combination of the tool and the right way to use it.

(Every tool can be used in different ways. For example, suppose you write a diary in MS Word. There are still options such as "one document per day" or "one very long document for all", and things in between like "one document per month", which all give different kinds of friction. The one megadocument takes too much time to load. It is more difficult to search in many small documents. Or maybe you should keep your current day in a small document, but once in a while merge the previous days into the megadocument? Or maybe switch to some application that starts faster than MS Word?)

Forgetting is an important part. Even if you want to remember forever, you need some form of deprioritizing. Something like "pages you haven't used for months will get smaller, and if you search for keywords, they will be at the bottom of the result list". But if one of them suddenly becomes relevant again, maybe the connected ones become relevant, too? Something like associations in brain. The idea is that remembering the facts is only a part of the problem; making the relevant ones more accessible is another. Because searching in too much data is ultimately just another kind of friction.

It feels like a smaller version of the internet. Years ago, the problem used to be "too little information", now the problem is "too much information, can't find the thing I actually want".

Perhaps a wiki, where the pages could get flagged as "important now" and "unimportant"? Or maybe, important for a specific context? And by default, when you choose a context, you would only see the important pages, and the rest of that only if you search for a specific keyword or follow a grey link. (Which again would require some work creating and maintaining the contexts. And that work should also be as frictionless as possible.)

@dkl9 wrote a very eloquent and concise piece arguing in favor of ditching "second brain" systems in favor of SRSs (Spaced Repetition Systems, such as Anki).

Try as you might to shrink the margin with better technology, recalling knowledge from within is necessarily faster and more intuitive than accessing a tool. When spaced repetition fails (as it should, up to 10% of the time), you can gracefully degrade by searching your SRS' deck of facts.

If you lose your second brain (your files get corrupted, a cloud service shuts down, etc), you forget its content, except for the bits you accidentally remember by seeing many times. If you lose your SRS, you still remember over 90% of your material, as guaranteed by the algorithm, and the obsolete parts gradually decay. A second brain is more robust to physical or chemical damage to your first brain. But if your first brain is damaged as such, you probably have higher priorities than any particular topic of global knowledge you explicitly studied.

I write for only these reasons:

- to help me think

- to communicate and teach (as here)

- to distill knowledge to put in my SRS

- to record local facts for possible future reference

Linear, isolated documents suffice for all those purposes. Once you can memorise well, a second brain becomes redundant tedium.

I like to think of learning and all of these things as self-contained smaller self-contained knowledge trees. Building knowledge trees that are cached, almost like creatin zip files and systems where I store a bunch of zip files similar to what Elizier talks about in The Sequences.

Like when you mention the thing about Nielsen on linear algebra it opens up the entire though tree there. I might just get the association to something like PCA and then I think huh, how to ptimise this and then it goes to QR-algorithms and things like a householder matrix and some specific symmetric properties of linear spaces...

If I have enough of these in an area then I might go back to my anki for that specific area. Like if you think from the perspective of schedulling and storage algorithms similar to what is explored in algorithms to live by you quickly understand that the magic is in information compression and working at different meta-levels. Zipped zip files with algorithms to expand them if need be. Dunno if that makes sense, agree with the exobrain creep that exists though.

I currently work in policy research, which feels very different from my intrinsic aesthetic inclination, in a way that I think Tanner Greer captures well in The Silicon Valley Canon: On the Paıdeía of the American Tech Elite:

I often draw a distinction between the political elites of Washington DC and the industrial elites of Silicon Valley with a joke: in San Francisco reading books, and talking about what you have read, is a matter of high prestige. Not so in Washington DC. In Washington people never read books—they just write them.

To write a book, of course, one must read a good few. But the distinction I drive at is quite real. In Washington, the man of ideas is a wonk. The wonk is not a generalist. The ideal wonk knows more about his or her chosen topic than you ever will. She can comment on every line of a select arms limitation treaty, recite all Chinese human rights violations that occurred in the year 2023, or explain to you the exact implications of the new residential clean energy tax credit—but never all at once. ...

Washington intellectuals are masters of small mountains. Some of their peaks are more difficult to summit than others. Many smaller slopes are nonetheless jagged and foreboding; climbing these is a mark of true intellectual achievement. But whether the way is smoothly paved or roughly made, the destinations are the same: small heights, little occupied. Those who reach these heights can rest secure. Out of humanity’s many billions there are only a handful of individuals who know their chosen domain as well as they do. They have mastered their mountain: they know its every crag, they have walked its every gully. But it is a small mountain. At its summit their field of view is limited to the narrow range of their own expertise.

In Washington that is no insult: both legislators and regulators call on the man of deep but narrow learning. Yet I trust you now see why a city full of such men has so little love for books. One must read many books, laws, and reports to fully master one’s small mountain, but these are books, laws, and reports that the men of other mountains do not care about. One is strongly encouraged to write books (or reports, which are simply books made less sexy by having an “executive summary” tacked up front) but again, the books one writes will be read only by the elect few climbing your mountain.

The social function of such a book is entirely unrelated to its erudition, elegance, or analytical clarity. It is only partially related to the actual ideas or policy recommendations inside it. In this world of small mountains, books and reports are a sort of proof, a sign of achievement that can be seen by climbers of other peaks. An author has mastered her mountain. The wonk thirsts for authority: once she has written a book, other wonks will give it to her.

While I don't work in Washington, this description rings true to my experience, and I find it aesthetically undesirable. Greer contrasts this with the Silicon Valley aesthetic, which is far more like the communities I'm familiar with:

The technologists of Silicon Valley do not believe in authority. They merrily ignore credentials, discount expertise, and rebel against everything settled and staid. There is a charming arrogance to their attitude. This arrogance is not entirely unfounded. The heroes of this industry are men who understood in their youth that some pillar of the global economy might be completely overturned by an emerging technology. These industries were helmed by men with decades of experience; they spent millions—in some cases, billions—of dollars on strategic planning and market analysis. They employed thousands of economists and business strategists, all with impeccable credentials. Arrayed against these forces were a gaggle of nerds not yet thirty. They were armed with nothing but some seed funding, insight, and an indomitable urge to conquer.

And so they conquered.

This is the story the old men of the Valley tell; it is the dream that the young men of the Valley strive for. For our purposes it shapes the mindset of Silicon Valley in two powerful ways. The first is a distrust of established expertise. The technologist knows he is smart—and in terms of raw intelligence, he is in fact often smarter than any random small-mountain subject expert he might encounter. But intelligence is only one of the two altars worshiped in Silicon Valley. The other is action. The founders of the Valley invariably think of themselves as men of action: they code, they build, disrupt, they invent, they conquer. This is a culture where insight, intelligence, and knowledge are treasured—but treasured as tools of action, not goods in and of themselves.

This silicon union of intellect and action creates a culture fond of big ideas. The expectation that anyone sufficiently intelligent can grasp, and perhaps master, any conceivable subject incentivizes technologists to become conversant in as many subjects as possible. The technologist is thus attracted to general, sweeping ideas with application across many fields. To a remarkable extent conversations at San Fransisco dinner parties morph into passionate discussions of philosophy, literature, psychology, and natural science. If the Washington intellectual aims for authority and expertise, the Silicon Valley intellectual seeks novel or counter-intuitive insights. He claims to judge ideas on their utility; in practice I find he cares mostly for how interesting an idea seems at first glance. He likes concepts that force him to puzzle and ponder.

This is fertile soil for the dabbler, the heretic, and the philosopher from first principles. It is also a good breeding ground for books. Not for writing books—being men of action, most Silicon Valley sorts do not have time to write books. But they make time to read books—or barring that, time to read the number of book reviews or podcast interviews needed to fool other people into thinking they have read a book (As an aside: I suspect this accounts somewhat for the popularity of this blog among the technologists. I am an able dealer in second-hand ideas).

I enjoyed Brian Potter's Energy infrastructure cheat sheet tables over at Construction Physics, it's a great fact post. Here are some of Brian's tables — if they whet your appetite, do check out his full essay.

Energy quantities:

Units and quantities | Kilowatt-hours | Megawatt-hours | Gigawatt-hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 British Thermal Unit (BTU) | 0.000293 | ||

| iPhone 14 battery | 0.012700 | ||

| 1 pound of a Tesla battery pack | 0.1 | ||

| 1 cubic foot of natural gas | 0.3 | ||

| 2000 calories of food | 2.3 | ||

| 1 pound of coal | 2.95 | ||

| 1 gallon of milk (calorie value) | 3.0 | ||

| 1 gallon of gas | 33.7 | ||

| Tesla Model 3 standard battery pack | 57.5 | ||

| Typical ICE car gas tank (15 gallons) | 506 | ||

| 1 ton of TNT | 1,162 | ||

| 1 barrel of oil | 1,700 | ||

| 1 ton of oil | 11,629 | 12 | |

| Tanker truck full of gasoline (9300 gallons) | 313,410 | 313 | |

| LNG carrier (180,000 cubic meters) | 1,125,214,740 | 1,125,215 | 1,125 |

| 1 million tons of TNT (1 megaton) | 1,162,223,152 | 1,162,223 | 1,162 |

| Oil supertanker (2 million barrels) | 3,400,000,000 | 3,400,000 | 3,400 |

It's amazing that a Tesla Model 3's standard battery pack has an OOM less energy capacity than a typical 15-gallon ICE car gas tank, and is probably heavier too, yet a Model 3 isn't too far behind in range and is far more performant. It's also amazing that an oil supertanker carries ~3 megatons(!) of TNT worth of energy.

Energy of various activities:

| Activity | Kilowatt-hours |

|---|---|

| Fired 9mm bullet | 0.0001389 |

| Making 1 pound of steel in an electric arc furnace | 0.238 |

| Driving a mile in a Tesla Model 3 | 0.240 |

| Making 1 pound of cement | 0.478 |

| Driving a mile in a 2025 ICE Toyota Corolla | 0.950 |

| Boiling a gallon of room temperature water | 2.7 |

| Synthesizing 1 kilogram of ammonia (NH3) via Haber-Bosch | 11.4 |

| Making 1 pound of aluminum via Hall-Heroult process | 7.0 |

| Average US household monthly electricity use | 899.0 |

| Moving a shipping container from Shanghai to Los Angeles | 2,000.0 |

| Average US household monthly gasoline use | 2,010.8 |

| Heating and cooling a 2500 ft2 home in California for a year | 4,615.9 |

| Heating and cooling a 2500 ft2 home in New York for a year | 23,445.8 |

| Average annual US energy consumption per capita | 81,900.0 |

Power output:

Activity or infrastructure | Kilowatts | Megawatts | Gigawatts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable daily output of a laborer | 0.08 | ||

| Output from 1 square meter of typical solar panels (21% efficiency) | 0.21 | ||

| Tesla wall connector | 11.50 | ||

| Tesla supercharger | 250 | ||

| Large on-shore wind turbine | 6,100 | 6 | |

| Typical electrical distribution line (15 kV) | 8,000 | 8 | |

| Large off-shore wind turbine | 14,700 | 15 | |

| Typical US gas pump | 20,220 | 20 | |

| Typical daily production of an oil well (500 barrels) | 35,417 | 35 | |

| Typical transmission line (150 kV) | 150,000 | 150 | |

| Large gas station (20 pumps) | 404,400 | 404 | |

| Large gas turbine | 500,000 | 500 | |

| Output from 1 square mile of typical solar panels | 543,900 | 544 | |

| Electrical output of a large nuclear power reactor | 1,000,000 | 1,000 | 1 |

| Single LNG carrier crossing the Atlantic (18 day trip time) | 2,604,664 | 2,605 | 3 |

| Nord Stream Gas pipeline | 33,582,500 | 33,583 | 34 |

| Trans Alaska pipeline | 151,300,000 | 151,300 | 151 |

| US electrical generation capacity | 1,189,000,000 | 1,189,000 | 1,189 |

This observation by Brian is remarkable:

A typical US gas pump operates at 10 gallons per minute (600 gallons an hour). At 33.7 kilowatt-hours per gallon of gas, that’s a power output of over 20 megawatts, greater than the power output of an 800-foot tall offshore wind turbine. The Trans-Alaska pipeline, a 4-foot diameter pipe, can move as much energy as 1,000 medium-sized transmission lines, and 8 such pipelines would move more energy than provided by every US electrical power plant combined.

US energy flows Sankey diagram by LLNL (a "quad" is short for “a quadrillion British Thermal Units,” or 293 terawatt-hours):

I had a vague inkling that a lot of energy is lost on the way to useful consumption, but I was surprised by the two-thirds fraction; the 61.5 quads of rejected energy is more than every other country in the world consumes except China. I also wrongly thought that the largest source of inefficiency was in transmission losses. Brian explains:

The biggest source of losses is probably heat engine inefficiencies. In our hydrocarbon-based energy economy, we often need to transform energy by burning fuel and converting the heat into useful work. There are limits to how efficiently we can transform heat into mechanical work (for more about how heat engines work, see my essay about gas turbines).

The thermal efficiency of an engine is the fraction of heat energy it can transform into useful work. Coal power plant typically operates at around 30 to 40% thermal efficiency. A combined cycle gas turbine will hit closer to 60% thermal efficiency. A gas-powered car, on the other hand, operates at around 25% thermal efficiency. The large fraction of energy lost by heat engines is why some thermal electricity generation plants list their capacity in MWe, the power output in megawatts of electricity.

Most other losses aren’t so egregious, but they show up at every step of the energy transportation chain. Moving electricity along transmission and distribution lines results in losses as some electrical energy gets converted into heat. Electrical transformers, which minimize these losses by transforming electrical energy into high-voltage, low-current before transmission, operate at around 98% efficiency or more.

I also didn't realise that biomass is so much larger than solar in the US (I expect this of developing countries), although likely not for long given the ~25% annual growth rate.

Energy conversion efficiency:

Energy equipment or infrastructure | Conversion efficiency |

|---|---|

| Tesla Model 3 electric motor | 97% |

| Electrical transformer | 97-99% |

| Transmission lines | 96-98% |

| Hydroelectric dam | 90% |

| Lithium-ion battery | 86-99+% |

| Natural gas furnace | 80-95% |

| Max multi-layer solar cell efficiency on earth | 68.70% |

| Max theoretical wind turbine efficiency (Betz limit) | 59% |

| Combined cycle natural gas plant | 55-60% |

| Typical wind turbine | 50% |

| Gas water heater | 50-60% |

| Typical US coal power plant | 33% |

| Max theoretical single-layer solar cell efficiency | 33.16% |

| Heat pump | 300-400% |

| Typical solar panel | 21% |

| Typical ICE car | 16-25% |

Finally, (US) storage:

Type | Quads of capacity |

|---|---|

| Grid electrical storage | 0.002 |

| Gas station underground tanks | 0.26 |

| Petroleum refineries | 3.58 |

| Other crude oil | 3.79 |

| Strategic petroleum reserve | 4.14 |

| Natural gas fields | 5.18 |

| Bulk petroleum terminals | 5.64 |

| Total | 22.59 |

I vaguely knew grid energy storage was much less than hydrocarbon, but I didn't realise it was 10,000 times less!

Peter Watts' 2006 novel Blindsight has this passage on what it's like to be a "scrambler", superintelligent yet nonsentient (in fact superintelligent because it's unencumbered by sentience), which I read a ~decade ago and found unforgettable:

Imagine you're a scrambler.

Imagine you have intellect but no insight, agendas but no awareness. Your circuitry hums with strategies for survival and persistence, flexible, intelligent, even technological—but no other circuitry monitors it. You can think of anything, yet are conscious of nothing.

You can't imagine such a being, can you? The term being doesn't even seem to apply, in some fundamental way you can't quite put your finger on.

Try.