I think this project should receive more red-teaming before it gets funded.

Naively, it would seem that the "second species argument" matches much more strongly to the creation of a hypothetical Homo supersapiens than it does to AGI.

We've observed many warning shots regarding catastrophic human misalignment. The human alignment problem isn't easy. And "intelligence" seems to be a key part of the human alignment picture. Humans often lack respect or compassion for other animals that they deem intellectually inferior -- e.g. arguing that because those other animals lack cognitive capabilities we have, they shouldn't be considered morally relevant. There's a decent chance that Homo supersapiens would think along similar lines, and reiterate our species' grim history of mistreating those we consider our intellectual inferiors.

It feels like people are deferring to Eliezer a lot here, which seems unjustified given how much strategic influence Eliezer had before AI became a big thing, and how poorly things have gone (by Eliezer's own lights!) since then. There's been very little reasoning transparency in Eliezer's push for genetic enhancement. I just don't see why we're deferring to Eliezer so much as a strategist, when I struggle to name a single major strategic success of his.

You shouldn't and won't be satisfied with this alone, as it doesn't deal with or even emphasize any particular peril; but to be clear, I have definitely thought about the perils: https://berkeleygenomics.org/articles/Potential_perils_of_germline_genomic_engineering.html

Right now only low-E tier human intelligences are being discussed, they'll be able to procreate with humans and be a minority.

Considering current human distributions and a lack of 160+ IQ people having written off sub-100 IQ populations as morally useless I doubt a new sub-population at 200+ is going to suddenly turn on humanity

If you go straight to 1000IQ or something sure, we might be like animals compared to them

Not sure why the holocaust is relevant.

60 IQ humans are defective, generally incapable of taking care of themselves, are unproductive and without a lot of effort by others have bad lives.

Of course we'd rather new humans be 100 IQ rather than 60 IQ. Even so, it's generally accepted that killing them, forcefully sterilizing (at least those who are aware) is immoral. Which means that despite incentives the majority population treats them as members of the same race and morally relevant.

(Contrast with current humanity - people are useful and can produce more than they eat, so there's no incentive to get rid of them. Further, you only need more selection for improvement, no sterilization necessary)

This new subpopulation would be much smaller than the 140+IQ group (I doubt we're getting 2 million 200IQ+ people very quickly), and also 140IQ people aren't interested in killing off everyone else...

If this new population wants to agitate for making new humans with high IQs I don't see that as a threat.

Eugenics for memes seems closer to sci-fi right now and unless done really stupidly seems irrelevant

At the end of 2023, MIRI had ~$19.8 mio. in assets. I don't know much about the legal restrictions of how that money could be used, or what the state for financial assets is now, but if it's similar then MIRI could comfortably fund Velychko's primate experiments, and potentially some additional smaller projects.

(Potentially relevant: I entered the last GWWC donor lottery with the hopes of donating the resulting money to intelligence enhancement, but wasn't selected.)

How robust are these calculations against the possibility that individual gene effects aren't simply additional but might even not play well together? i.e. gene variant #1 raises your IQ by 2 points, variant #2 raises your IQ by 1 point, but variants #1+2 together make you able to multiply twelve-digit numbers in your head but unable to tie your shoes; or variant #3 lifts your life expectancy by making you less prone to autoimmune disease A, variant #4 makes you less prone to autoimmune disease B, but variants #3+4 together make you succumb to the common cold because your immune system is not up to the task.

It's hard for me to tell from the level of detail in your explanation here, but at times it seems like you're just naively stacking the ostensible effects of particular gene variants one on top of the other and then measuring the stack.

It's a good question. The remarkable thing about human genetics is that most of the variants ARE additive.

This sounds overly simplistic, like it couldn't possible work, but it's one of the most widely replicated results in the field.

There ARE some exceptions. Personality traits seem to be mostly the result of gene-gene interactions, which is one reason why SNP heritability (additive variance explained by common variants) is so low.

But for nearly all diseases and for many other traits like height and intelligence, ~80% of variance is additive. somewhere between 50 and 80% of the heritable variance is additive. And basically ALL of the variance we can identify with current genetic predictors is additive.

This might seem like a weird coincidence. After all, we know there is a lot of non-linearity in actual gene regulatory networks. So how could it be that all the common variants simply add together?

There's a pretty clear reason from an evolutionary point of view: evolution is able to operate on genes with additive effects much more easily than on those with non-additive effects.

The set of genetic variants inherited is scrambled every generation during the sperm and egg formation proces...

The remarkable thing about human genetics is that most of the variants ARE additive.

I think this is likely incorrect, at least where intelligence-affecting SNPs stacked in large numbers are concerned.

To make an analogy to ML, the effect of a brain-affecting gene will be to push a hyperparameter in one direction or the other. If that hyperparameter is (on average) not perfectly tuned, then one of the variants will be an enhancement, since it leads to a hyperparameter-value that is (on average) closer to optimal.

If each hyperparameter is affected by many genes (or, almost-equivalently, if the number of genes greatly exceeds the number of hyperparameters), then intelligence-affecting traits will look additive so long as you only look at pairs, because most pairs you look at will not affect the same hyperparameter, and when they do affect the same hyperparameter the combined effect still won't be large enough to overshoot the optimum. However, if you stack many gene edits, and this model of genes mapping to hyperparameters is correct, then the most likely outcome is that you move each hyperparameter in the correct direction but overshooting the optimum. Phrased slightly differently: in...

Thanks. I think it's an important point you make; I do have it in mind that traits can have nonlinearities at different "stages", but I hadn't connected that to the personality trait issue. I don't immediately see a very strong+clear argument for personality traits being super exceptional here. Intuitively it makes sense that they're more "complicated" or "involve more volatile forces" or something due to being mental traits, but a bit more clarity would help. In particular, I don't see the argument being able to support yes significant broadsense heritability but very little apparent narrowsense heritability. (Though maybe it can somehow.)

(Also btw I wouldn't exactly call multiplicativity by itself "nonlinearity"! I would just say that after the genomic fan-in there is a nonlinearity. It's linearity as long as there's a latent variable that's a sum of alleles. Indeed, as E.G. pointed out to me, IQ could very well be like this, i.e. IQ-associated traits might be even better predicted by assuming IQ is lognormal (or some other such distribution). Though of course then you can't say that such and such downstream outcome is linear in genes; but the point would be that you can push alo...

That’s just a massive source of complexity, obfuscating the relationship between inputs and outputs.

A kind of analogy is: if you train a set of RL agents, each with slightly different reward functions, their eventual behavior will not be smoothly variant. Instead there will be lots of “phase shifts” and such.

And yet it moves! Somehow it's heritable! Do you agree there is a tension between heritability and your claims?

Ok, more specifically, the decrease in the narrowsense heritability gets "double-counted" (after you've computed the reduced coefficients, those coefficients also get applied to those who are low in the first chunk and not just those who are high, when you start making predictions), whereas the decrease in the broadsense heritability is only single-counted. Since the single-counting represents a genuine reduction while the double-counting represents a bias, it only really makes sense to think of the double-counting as pathological.

The "Black Death selection" finding you mention was subject to a very strong rebuttal preprinted in March 2023 and published yesterday in Nature. The original paper committed some pretty basic methodological errors[1] and, in my opinion, it's disappointing that Nature did not decide to retract it. None of their claims of selection – neither the headline ERAP2 variant or the "half a dozen others" you refer to – survive the rebuttal's more rigorous reanalysis. I do some work in ancient DNA and am aware of analyses on other datasets (published and unpublished) that fail to replicate the original paper's findings.

- ^

Some of the most glaring (but not necessarily most consequential): a failure to correctly estimate the allele frequencies underlying the selection analysis; use of a genotyping pipeline poorly suited to ancient DNA which meant that 80% of the genetic variants they "analysed" were likely completely artefactual and did not exist.

use of a genotyping pipeline poorly suited to ancient DNA which meant that 80% of the genetic variants they "analysed" were likely completely artefactual and did not exist.

Brutal!! I didn't know this gotcha existed. I hope there aren't too many papers silently gotch'd by it. Sounds like the type of error that could easily be widespread and unnoticed, if the statistical trace it leaves isn't always obvious.

Thanks for catching that! I hadn't heard. I will probably have to rewrite that section of the post.

What's your impression about the general finding about many autoimmune variants increasing protection against ancient plauges?

There are a couple of major problems with naively intervening to edit sites associated with some phenotype in a GWAS or polygenic risk score.

-

The SNP itself is (usually) not causal Genotyping arrays select SNPs the genotype of which is correlated with a region around the SNP, they are said to be in linkage with this region as this region tends to be inherited together when recombination happens in meiosis. This is a matter of degree and linkage scores allow thresholds to be set for how indicative a SNP is about the genotype a given region.

If it is not the SNP but rather something with which the SNP is in linkage that is causing the effect editing the SNP has no reason the effect the trait in question.

It is not trivial to figure out what in linkage with a SNP might be causing an effect.

Mendelian randomisation (explainer: https://www.bmj.com/content/362/bmj.k601) is a method that permits the identification of causal relationships from observational genetic studies which can help to overcome this issue. -

In practice epistatic interactions between QTLs matter for effects sizes and you cannot naively add up the effect sizes of all the QTLs for a trait and expect the result to refl

How much do people know about the genetic components of personality traits like empathy? Editing personality traits might be almost as or even more controversial than modifying “vanity” traits. But in the sane world you sketched out this could essentially be a very trivial and simple first step of alignment. “We are about to introduce agents more capable than any humans except for extreme outliers: let’s make them nice.” Also, curing personality disorders like NPD and BPD would do a lot of good for subjective wellbeing.

I guess I’m just thinking of a failure mode where we create superbabies who solve task-alignment and then control the world. The people running the world might be smarter than the current candidates for god-emperor, but we’re still in a god-emperor world. This also seems like the part of the plan most likely to fail. The people who would pursue making their children superbabies might be disinclined towards making their children more caring.

Very little at the moment. Unlike intelligence and health, a lot of the variance in personality traits seems to be the result of combinations of genes rather than purely additive effects.

This is one of the few areas where AI could potentially make a big difference. You need more complex models to figure out the relationship between genes and personality.

But the actual limiting factor right now is not model complexity, but rather data. Even if you have more complex models, I don't think you're going to be able to actually train them until you have a lot more data. Probably a minimum of a few million samples.

We'd like to look into this problem at some point and make scaling law graphs like the ones we made for intelligence and disease risk but haven't had the time yet.

This is starting to sound a lot like AI actually. There's a "capabilities problem" which is easy, an "alignment problem" which is hard, and people are charging ahead to work on capabilities while saying "gee, we'd really like to look into alignment at some point".

It's utterly different.

- Humans are very far from fooming.

- Fixed skull size; no in silico simulator.

- Highly dependent on childhood care.

- Highly dependent on culturally transmitted info, including in-person.

- Humans, genomically engineered or not, come with all the stuff that makes humans human. Fear, love, care, empathy, guilt, language, etc. (It should be banned, though, to remove any human universals, though defining that seems tricky.) So new humans are close to us in values-space, and come with the sort of corrigibility that humans have, which is, you know, not a guarantee of safety, but still some degree of (okay I'm going to say something that will trigger your buzzword detector but I think it's a fairly precise description of something clearly real) radical openness to co-creating shared values.

Humans are very far from fooming.

Tell that to all the other species that went extinct as a result of our activity on this planet?

I think it's possible that the first superbaby will be aligned, same way it's possible that the first AGI will be aligned. But it's far from a sure thing. It's true that the alignment problem is considerably different in character for humans vs AIs. Yet even in this particular community, it's far from solved -- consider Brent Dill, Ziz, Sam Bankman-Fried, etc.

Not to mention all of history's great villains, many of whom believed themselves to be superior to the people they afflicted. If we use genetic engineering to create humans which are actually, massively, undeniably superior to everyone else, surely that particular problem is only gonna get worse. If this enhancement technology is going to be widespread, we should be using the history of human activity on this planet as a prior. Especially the history of human behavior towards genetically distinct populations with overwhelming technological inferiority. And it's not pretty.

So yeah, there are many concrete details which differ between these two situations. But in terms of high-level strategic implications, I think there are important similarities. Given the benefit of hindsight, what should MIRI have done about AI back in 2005? Perhaps that's what we should be doing about superbabies now.

Tell that to all the other species that went extinct as a result of our activity on this planet?

Individual humans.

Brent Dill, Ziz, Sam Bankman-Fried, etc.

- These are incredibly small peanuts compared to AGI omnicide.

- You're somehow leaving out all the people who are smarter than those people, and who were great for the people around them and humanity? You've got like 99% actually alignment or something, and you're like "But there's some chance it'll go somewhat bad!"... Which, yes, we should think about this, and prepare and plan and prevent, but it's just a totally totally different calculus from AGI.

I'm saying that (waves hands vigorously) 99% of people are beneficent or "neutral" (like, maybe not helpful / generous / proactively kind, but not actively harmful, even given the choice) in both intention and in action. That type of neutral already counts as in a totally different league of being aligned compared to AGI.

one human group is vastly unaligned to another human group

Ok, yes, conflict between large groups is something to be worried about, though I don't much see the connection with germline engineering. I thought we were talking about, like, some liberal/techie/weirdo people have some really really smart kids, and then those kids are somehow a threat to the future of humanity that's comparable to a fast unbounded recursive self-improvement AGI foom.

I'm saying that (waves hands vigorously) 99% of people are beneficent or "neutral" (like, maybe not helpful / generous / proactively kind, but not actively harmful, even given the choice) in both intention and in action. That type of neutral already counts as in a totally different league of being aligned compared to AGI.

I think this is ultimately the crux, at least relative to my values, I'd expect at least 20% in America to support active efforts to harm me or my allies/people I'm altruistic to, and do so fairly gleefully (an underrated example here is voting for people that will bring mass harm to groups they hate, and hope that certain groups go extinct).

Ok, yes, conflict between large groups is something to be worried about, though I don't much see the connection with germline engineering. I thought we were talking about, like, some liberal/techie/weirdo people have some really really smart kids, and then those kids are somehow a threat to the future of humanity that's comparable to a fast unbounded recursive self-improvement AGI foom.

Okay, the connection was to point out that lots of humans are not in fact aligned with each other, and I don't particularly think superbabies are a threat to the future of humanity that is comparable to AGI, so my point was more so that the alignment problem is not naturally solved in human-to human interactions.

I mostly just want people to pay attention to this problem.

Ok. To be clear, I strongly agree with this. I think I've been responding to a claim (maybe explicit, or maybe implicit / imagined by me) from you like: "There's this risk, and therefore we should not do this.". Where I want to disagree with the implication, not the antecedent. (I hope to more gracefully agree with things like this. Also someone should make a LW post with a really catchy term for this implication / antecedent discourse thing, or link me the one that's already been written.)

But I do strongly disagree with the conclusion "...we should not do this", to the point where I say "We should basically do this as fast as possible, within the bounds of safety and sanity.". The benefits are large, the risks look not that bad and largely ameliorable, and in particular the need regarding existential risk is great and urgent.

That said, more analysis is definitely needed. Though in defense of the pro-germline engineering position, there's few resources, and everyone has a different objection.

I honestly think the EV of superhumans is lower than the EV for AI. sadism and wills to power are baked into almost every human mind (with the exception of outliers of course). force multiplying those instincts is much worse than an AI which simply decides to repurpose the atoms in a human for something else. i think people oftentimes act like the risk ends at existential risks, which i strongly disagree with. i would argue that everyone dying is actually a pretty great ending compared to hyperexistential risks. it is effectively +inf relative utility.

with AIs we're essentially putting them through selective pressures to promote benevolence (as a hedge by the labs in case they don't figure out intent alignment). that seems like a massive advantage compared to the evolutionary baggage associated with humans.

with humans you'd need the will and capability to engineer in at least +5sd empathy and -10sd sadism into every superbaby. but people wouldn't want their children to make them feel like shitty people so they would want them to "be more normal."

Agreed. I've actually had a post in draft for a couple of years that discusses some of the paralleles between alignment of AI agents and alignment of genetically engineered humans.

I think we have a huge advantage with humans simply because there isn't the same potential for runaway self-improvement. But in the long term (multiple generations), it would be a concern.

After I finish my methods article, I want to lay out a basic picture of genomic emancipation. Genomic emancipation means making genomic liberty a right and a practical option. In my vision, genomic liberty is quite broad: it would include for example that parents should be permitted and enabled to choose:

- to enhance their children (e.g. supra-normal health; IQ at the outer edges of the human envelope); and/or

- to propagate their own state even if others would object (e.g. blind people can choose to have blind children); and/or

- to make their children more normal even if there's no clear justification through beneficence (I would go so far as to say that, for example, parents can choose to make their kid have a lower IQ than a random embryo from the parents would be in expectation, if that brings the kid closer to what's normal).

These principles are more narrow than general genomic liberty ("parents can do whatever they please"), and I think have stronger justifications. I want to make these narrower "tentpole" principles inside of the genomic liberty tent, because the wider principle isn't really tenable, in part for the reasons you bring up. There are genomic choices that should ...

I'm surprised to see no one in the comments whose reaction is "KILL IT WITH FIRE", so I'll be that guy and make a case why this research should be stopped rather than pursued:

On the one hand, there is obviously enormous untapped potential in this technology. I don't have issues about the natural order of life or some WW2 eugenics trauma. From my (unfamiliar with the subject) eyes, you propose a credible way to make everyone healthier, smarter, happier, at low cost and within a generation, which is hard to argue against.

On the other hand, you spend no time mentioning the context in which this technology will be developed. I imagine there will be significant public backlash and that most advances on superbabies-making will be made by private labs funded by rich tech optimists, so it seems overwhelmingly likely to me that if this technology does get developed in the next 20 years, it will not improve everyone.

At this point, we're talking about the far future, so I need to make a caveat for AI: I have no idea how the new AI world will interact with this, but there are a few most likely futures I can condition on.

- Everyone dies: No point talking about superbabies.

- Cohabitive singlet

Are your IQ gain estimates based on plain GWAS or on family-fixed-effects-GWAS? You don't clarify. The latter would give much lower estimates than the former

Your OP is completely misleading if you're using plain GWAS!

GWAS is an association -- that's what the A stands for. Association is not causation. Anything that correlates with IQ (eg melanin) can show up in a GWAS for IQ. You're gonna end up editing embryos to have lower melanin and claiming their IQ is 150

You should show your calculation or your code, including all the data and parameter choices. Otherwise I can't evaluate this.

I assume you're picking parameters to exaggerate the effects, because just from the exaggerations you've already conceded (0.9/0.6 shouldn't be squared and attenuation to get direct effects should be 0.824), you've already exaggerated the results by a factor of sqrt(0.9/0.6)/0.824 for editing, which is around a 50% overestimate.

I don't think that was deliberate on your part, but I think wishful thinking and the desire to paint a compelling story (and get funding) is causing you to be biased in what you adjust for and in which mistakes you catch. It's natural in your position to scrutinize low estimates but not high ones. So to trust your numbers I'd need to understand how you got them.

There is one saving grace for us which is that the predictor we used is significantly less powerful than ones we know to exist.

I think when you account for both the squaring issue, the indirect effect things, and the more powerful predictors, they're going to roughly cancel out.

Granted, the more powerful predictor itself isn't published, so we can't rigorously evaluate it either which isn't ideal. I think the way to deal with this is to show a few lines: one for the "current publicly available GWAS", one showing a rough estimate of the gain using the privately developed predictor (which with enough work we could probably replicate), and then one or two more for different amounts of data.

All of this together WILL still reduce the "best case scenario" from editing relative to what we originally published (because with the better predictor we're closer to "perfect knowledge" than where we were with the previous predictor.

At some point we're going to re-run the calculations and publish an actual proper writeup on our methodology (likely with our code).

Also I just want to say thank you for taking the time to dive deep into this with us. One of the main reasons I post on LessWrong is because there is such high quality feedback relative to other sites.

May I ask what your respective scientific and genetics backgrounds are? I ask because this piece reads like many pieces where enthusiastic non-scientists pull together a bunch of papers without being able to assess the quality of those papers. I've also noticed a behaviour where you can't assess the quality of a paper then you over-estimate the positive effects that confirm your beliefs and ignore potential negative effects. This is an odd approach for most biologists I've worked with but is pretty typical of a layman. You also happy to work with single papers for many of your ideas, which again is something laymen inexperienced with scientific problems would do.

I definitely want to see more work in this direction, and agree that improving humans is a high-value goal.

But to play devil's advocate for a second on what I see as my big ethical concern: There's a step in the non-human selective breeding or genetic modification comparison where the experimenter watches several generations grow to maturity, evaluates whether their interventions worked in practice, and decides which experimental subjects if any get to survive or reproduce further. What's the plan for this step in humans, since "make the right prediction every time at the embryo stage" isn't a real option? '

Concrete version of that question: Suppose we implement this as a scalable commercial product and find out that e.g. it causes a horrible new disease, or induces sociopathic or psychopathic criminal tendencies, that manifest at age 30, after millions of parents have used it. What happens next?

I think almost everyone misunderstands the level of knowledge we have about what genetic variants will do.

Nature has literally run a randomized control trial for genes already. Every time two siblings are created, the set of genes they inherit from each parent are scrambled and (more or less) randomly assigned to each. That's INCREDIBLY powerful for assessing the effects of genes on life outcomes. Nature has run a literal multi-generational randomized control trial for the effect of genes on everything. We just need to collect the data.

This gives you a huge advantage over "shot-in-the-dark" type interventions where you're testing something without any knowledge about how it performs over the long run.

Also, nature is ALREADY running a giant parallelized experiment on us every time a new child is born. Again, the genes they get from their parents are randomized. If reshuffling genetic variants around were extremely dangerous we'd see a huge death rate in the newborn population. But that is not in fact what we see. You can in fact change around some common genetic variants without very much risk.

And if you have a better idea about what those genes do (which we increasingly do), then you can do even better.

There are still going to be risks, but the biggest ones I actually worry about are about getting the epigenetics right.

But there we can just copy what nature has done. We don't need to modify anything.

Ovelle, who is planning to use growth and transcription factors to replicate key parts of the environment in which eggs are produced rather than grow actual feeder cells to excrete those factors. If it works, this approach has the advantage of speed; it takes a long time to grow the feeder cells, so if you can bypass some of that you can make eggs more quickly. Based on some conversations I’ve had with one of the founders I think $50 million could probably accelerate progress by about a year.

A few comments on this:

1. The "feeder cells" you're discussing here are from the method in this paper from the Saitou lab, who used feeder cells to promote development of human PGC-like cells to oogonia. But "takes a long time to grow the feeder cells" is not the issue. In fact, the feeder cells are quite easy to grow. The issue is that it takes a long time for PGC-like cells to develop to eggs, if you're strictly following the natural developmental trajectory.

2. The $50 million number is for us to set up our own nonhuman primate research facility, which would accelerate our current trajectory by *approximately* a year. On our current trajectory, we are going to need to raise about $5-10 million in the near future to scale up our research. We have already raised $2.15 million and we will start fundraising again this summer. But it's not like we need $50 million to make progress (although it would certainly help!)

On the topic of SuperSOX and how it relates to making eggs from stem cells:

The requirement for an existing embryo (to transfer the edited stem cells into) means that having an abundant source of eggs is important for this method, both for optimizing the method by screening many conditions, and for eventual use in the clinic.

So, in vitro oogenesis could play a key role here.

For both technologies, I think the main bottleneck right now is nonhuman primate facilities for testing.

Finally: we need to be sure not to cause another He Jiankui event (where an irresponsible study resulted in a crackdown on the field). Epigenetic issues could cause birth defects, and if this happens, it will set back the field by quite a lot. So safety is important! Nobody cares if their baby has the genes for 200 IQ, if the baby also has Prader-Willi syndrome.

I'm having trouble understanding your ToC in a future influenced by AI. What's the point of investigating this if it takes 20 years to become significant?

One thing not mentioned here (and I think should be talked about more) is that the naturally occurring genetic distribution is very unequal in a moral sense. A more egalitarian society would put a stop to Eugenics Performed by a Blind, Idiot God.

Have your doctor ever asked about if you have a family history of [illness]? For so many diseases, if your parents have it, you're more likely to have it, and your kids are more likely to have it. These illnesses plague families for generations.

I have a higher than average chance of getting hypertension. Without technology, so will my future kids. With gene editing, we can just stop that, once and for all. A just world is a world where no child is born predetermined to endure avoidable illness simply because of ancestral bad luck.

However, the difference is especially salient because the person deciding isn't the person that has to live with said genes. The two people may have different moral philosophies and/or different risk preferences.

A good rule might be that the parents can only select alleles that one or the other of them have, and also have the right to do so as they choose, under the principle that they have lived with it. (Maybe with an exception for the unambiguously bad alleles, though even in that case it's unlikely that all four of the parent's alleles are the deleterious one or that the parents would want to select it.) Having the right to select helps protect from society/govt imposing certain traits as more or less valuable, and keeping within the parent's alleles maintains inheritance, which I think are two of the most important things people opposed to this sort of thing want to protect.

And these changes in chickens are mostly NOT the result of new mutations, but rather the result of getting all the big chicken genes into a single chicken.

Is there a citation for this? Or is that just a guess

Thanks for the write-up, I recall a conversation introducing me to all these ideas in Berkeley last year and it's going to be very handy having a resource to point people at (and so I don't misremember details about things like the Yamanaka factors!).

Am I reading the current plan correctly such that the path is something like:

Get funding -> Continue R+D through primate trials -> Create an entity in a science-friendly, non-US state for human trials -> first rounds of Superbabies? That scenario seems like it would require a bunch of medical tourism, which I imagine is probably not off the table for people with the resources and mindset willing to participate in this.

Yes, that's more or less the plan. I think it's pretty much inevitable that the United States will fully legalize germline gene editing at some point. It's going to be pretty embarassing if rich American parents are flying abroad to have healthier children.

You can already see the tide starting to turn on this. Last Month Nature actually published an article about germline gene editing. That would NEVER have happened even just a few years ago.

When you go to CRISPR conferences on gene editing, many of the scientists will tell you in private that germline gene editing makes sense. But if you ask them to go on the record as supporting it publicly, they will of course refuse.

At some point there's going to be a preference cascade. People are going to start wondering why the US government is blocking technology to its future citizens healthier, happier, and smarter.

First, sorry in advance for the annoying unimportant nitpick and thank you for this exquisite resource.

too busy with their washing machines to think about light bulbs or computers

I think washing machines are not the best metaphor. They have actually contributed quite considerably to global economic growth in the past half century, as researched and explained by Economics Explained.

Perhaps something more like electric heated seats would be more fitting?

We’ve successfully extracted and cultured human spermatogonial stem cells back in 2020.

To be clear, this paper AFAICT did not directly measure epigenomic state, and specifically imprinting state. (Which makes sense given what they were trying to do. In theory the imprints might show up in their transcriptomics, but who knows, and they didn't report that.) We don't know whether imprinting would be maintained for a great length of time in culture with their method.

Curated. Genetically enhanced humans are my best guess for how we achieve existential safety. (Depending on timelines, they may require a coordinated slowdown to work). This post is a pretty readable introduction to a bunch of the why and how and what still needs to be down.

I think this post is maybe slightly too focused on "how to genetically edit for superbabies" to fully deserve its title. I hope we get a treatment of more selection-based methods sometime soon.

GeneSmith mentioned the high-quality discussion as a reason to post here, and I'm glad we're a...

Your introduction describes how I feel about my area of expertise too!

Working in the field of *neuroscience* is a bizarre experience. No one seems to be interested in the most interesting applications of their research. Neuroscience has significantly advanced in the past few decades. I keep telling people that soon we're all going to have self driving cars powerd by a horse's brain in a glass jar. Most people just laugh in disbelief, others make frightened noises and mention "ethical issues" or change the subject. The smart money is off chasing the deep learning pipe dream, and as a direct consequence, there is low-hanging fruit absolutely everywhere.

Have you thought about how to get the data yourself?

Perhaps offering payment to people willing to get iq tested and give a genetic sample, and paying more for higher scores on the test?

I understand that money is an issue, but as long as you're raising this seems like an area you could plug infinite money into and get returns

I feel that this project would be unethical to undertake, and I will try to explain why I get that reading.

It's not that I think using genetic engineering on children is categorically wrong. Mutations occur in every new human, and adding in some that seem likely to come in handy later is something one can make an argument for. A person's genome is the toolbox their body has to deal with the world, and it might be right to stock it with more tools.

But I think it is wrong to instrumentalize children in this way. If you go through many rounds of editing, each...

I think many people in academia more or less share your viewpoint.

Obviously genetic engineering does add SOME additional risk of people coming to see human children like commodities, but in my view it's massively outweighed by the potential benefits.

you end up with a child whose purpose is to fulfill the parameters of their human designers

I think whether or not people (and especially parents) view their children this way depends much more on cultural values and much less on technology.

There are already some parents who have very specific goals in mind for their children and work obsessively to realize them. This doesn't always work that well, and I'm not sure it will work that well even with genetic engineering.

Sure we will EVENTUALLY be able to shape personality better with gene editing (though I would note we don't really have the ability to do so currently), but human beings are very complicated. Gene editing is a fairly crude tool for shaping human behavior. You can twist the knobs for dozens of human traits, but I think anyone trying to predetermine their child's future is going to be disappointed.

...The tremendous effort involved in trying to fit the child to the design pa

A person with HIV and a person without are both worth unity. These are fundamental results in disability studies.

Where are these studies that have results which are object-level ethical claims…? This seems not just improbable, but outright incoherent. Do you have any links to studies like this?

Someone please tell Altman and Musk they can spend their fortunes on millions of uber-genius children if they please, and they don't have to spend it all on their contest to replace ourselves with the steel & copper successors.

Nobel prize winners (especially those in math and sciences) tend to have IQs significantly above the population average.

There is no Nobel prize in math. And the word "especially" would imply that there exists data on the IQs of Nobel laureates in literature and peace which shows a weaker trend than the trend for sciences laureates; has anybody ever managed to convince a bunch of literature Nobel laureates to take IQ tests? I can't find anything by Googling, and I'm skeptical.

To be clear, the general claim that people who win prestigious STEM awards have above-average IQs is obviously true.

(To be clear: I agree with the rest of the OP, and with your last remark.)

has anybody ever managed to convince a bunch of literature Nobel laureates to take IQ tests? I can't find anything by Googling, and I'm skeptical.

I just read this piece by Erik Hoel which has this passage relevant to that one particular sentence you quoted from the OP:

...Consider a book from the 1950s, The Making of a Scientist by psychologist and Harvard professor Anne Roe, in which she supposedly measured the IQ of Nobel Prize winners. The book is occasionally dug up and used as evidence that Nobel Prize winners have an extremely high IQ, like 160 plus. But it’s really an example of how many studies of genius are methodologically deeply flawed. ...

Roe never used an official IQ tests on her subjects, the Nobel Prize winners. Rather, she made up her test, simply a timed test that used SAT questions of the day. Why? Because most IQ tests have ceilings (you can only score like a 130 or 140 on them) and Roe thought—without any evidence or testing—that would be too low for the Nobel Prize winners. And while she got some help with this from the organization that created the SATs, she admits:

The test I used is not one

Unfortunately monkeys (specifically marmosets) are not cheap. To demonstrate germline transmission (the first step towards demonstrating safety in humans), Sergiy needs $4 million.

And marmosets are actually the cheapest monkey. (Also, as New World monkeys, marmosets are more distantly related to humans than rhesus or cynomolgus monkeys are.)

As a rough estimate, I think 3x to 5x more expensive. Marmosets are smaller (smaller than squirrels) whereas macaques (rhesus/cyno) are about 10x bigger (6 kg). And macaques take longer to develop (3 years vs. 18 months until adulthood). Finally, macaques are in high demand and low supply for pharma research.

But the benefit is that methods developed in macaques are more likely to translate to humans, due to the closer evolutionary relationship. Marmosets are a bit unusual in their embryonic development (two twin embryos share a common, fused placenta!)

From a sales perspective, I find myself bewildered by the approach this article takes to ethics. Deriding ethical concerns then launching into a grassroots campaign for fringe primate research into genetic hygiene and human alignment is nonstarter for changing opinions.

This article, and another here about germ engineering, are written as if the concepts are new. The reality is that these are 19th century ideas and early attempts to implement them are the reason for the ethical concerns.

Using the standard analogical language of this site, AI and...

I'm not quite convinced by the big chicken argument. A much more convincing argument would be genetically selecting giraffes to be taller or cheetah to be faster.

That is, it's plausible evolution has already taken all the easy wins with human intelligence, in a way it hasn't with chicken size.

If evolution has already taken all the easy wins, why do humans vary so much in intelligence in the first place? I don't think the answer is mutation-selection balance, since a good chunk of the variance is explained by additive effects from common SNPs. Further, if you look at the joint distribution over effect sizes and allele frequencies among SNPs, there isn't any clear skew towards rarer alleles being IQ-decreasing.

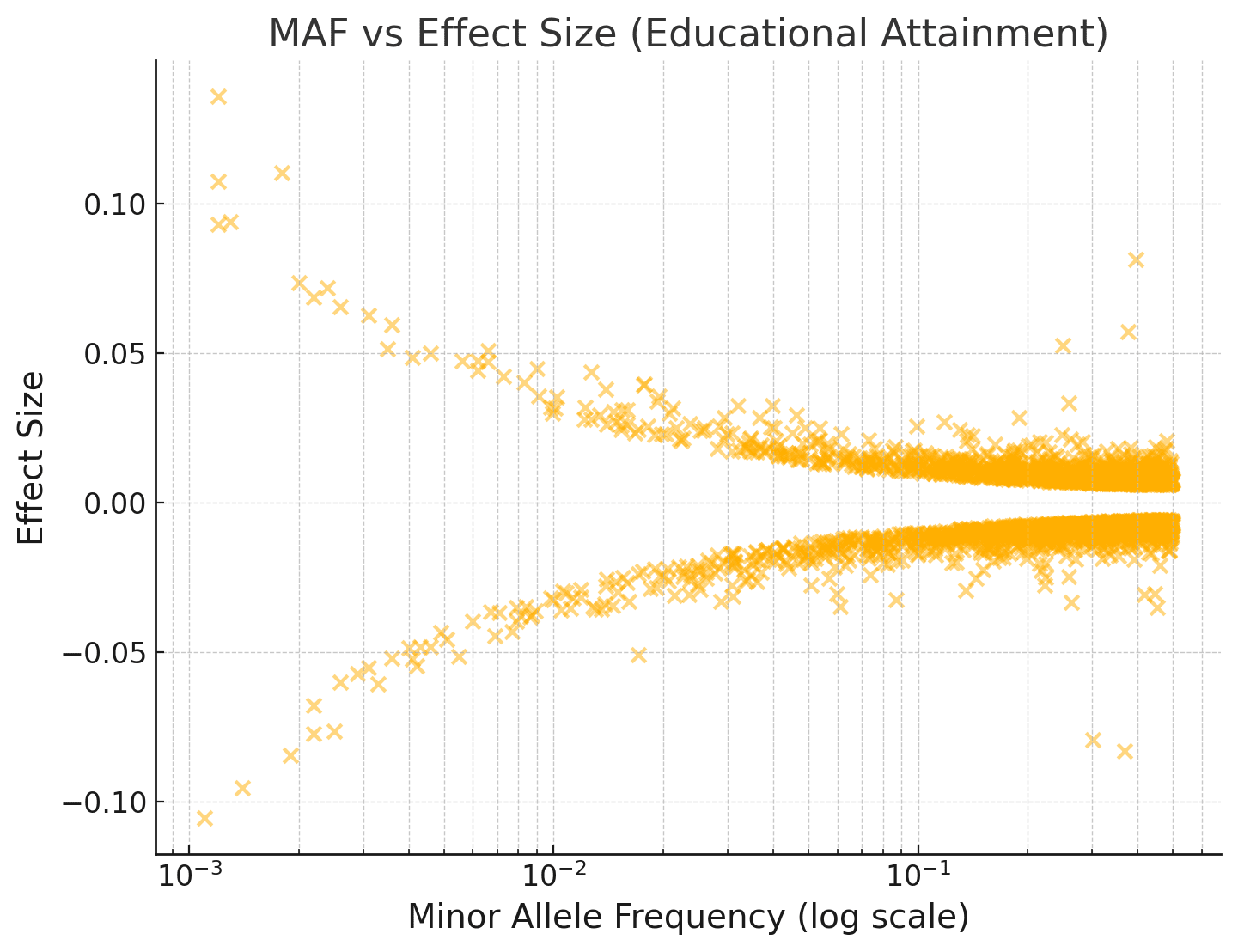

For example, see the plot below of minor allele frequency vs the effect size of the minor allele. (This is for Educational Attainment, a highly genetically correlated trait, rather than IQ, since the EA GWAS is way larger and has way more hits.)

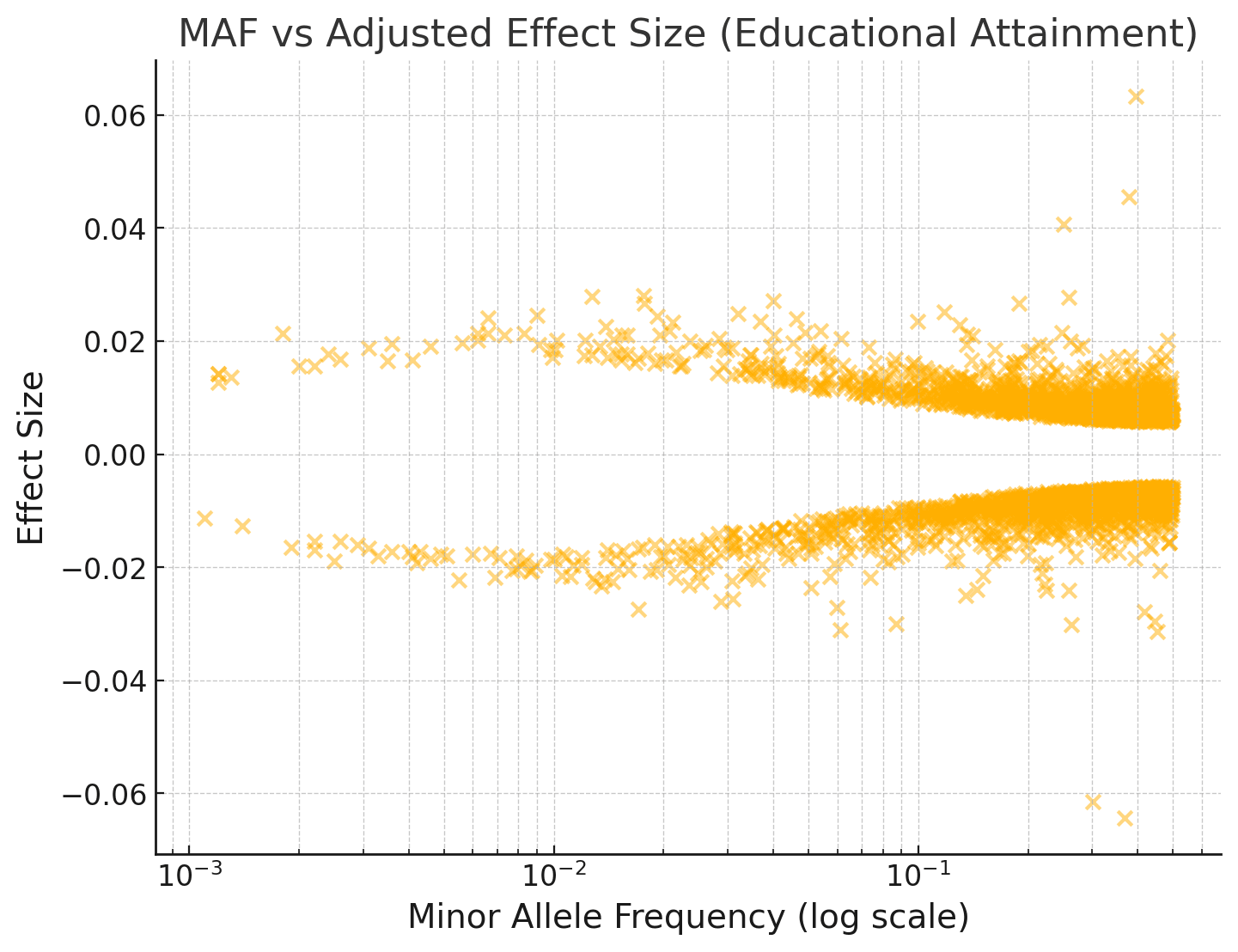

If we do a Bayesian adjustment of the effect sizes for observation noise, assuming EA has a SNP heritability of 0.2 and 20,000 causal variants with normally distributed effects:

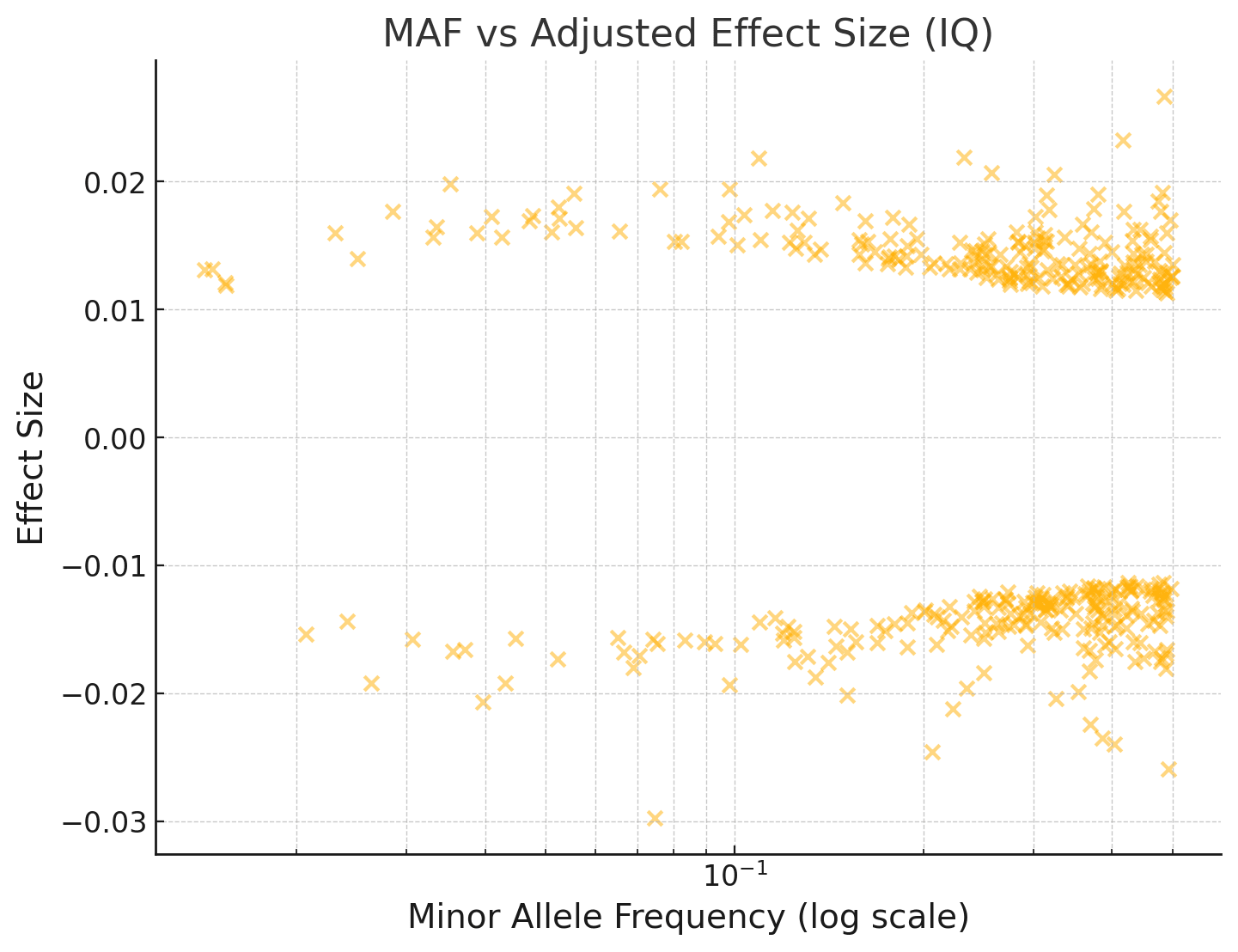

I've repeated this below for an IQ GWAS:

You can see that the effect sizes look roughly symmetrically distributed about zero, even for fairly rare SNPs with MAF < 1%.

The problem is with society, politics and ethics, rather than a technical problem. in addition to a technical problem.

I think the solution should be to vividly demonstrate how effective and safe it is with animal studies, so that a lot of normal people will want to do it, and feel that not doing it is scarier than doing it.

If a lot of normal people want it, they will be able to get it one way or another (flying to another country, etc.).

I've just started reading and this seems very interesting and important. However, I find the discussion about embryos and scaling odd. I mean sentences like "If we had 500 embryos". Here is some quick info for women under 35, generated by ChatGPT:

- A single egg collection usually retrieves 8-14 eggs. Out of those, only 4-6 embryos typically develop far enough to be tested, and about 50-60% of those will be genetically normal. This means that in most cases, only 2-4 embryos per cycle are actually viable for implantation.

- Even in the best-case scenario, only ab

I'm preemptively sorry if this question have already been raised, I don't feel like reading all the comments.

What am I doing now is reciting the points from Habr (a mostly-coding-oriented site where this article have been translated in Russian and criticized in comments)

The main criticism is against the key point of the article, the graphs of "edit N genes, get M bonus to IQ".

The arguments are:

- There are only a few hundred IQ-related genes, and they're found through a correlation in over 240k people, so it's not necessary that you can just

Thank you for writing this article! It was extremely informative and I am very pleased to learn about super-SOX. I have been looking for a process which can turn somatic cells into embryonic stem cells due to unusual personal reasons, so by uncovering this technology you have done me a great service. Additionally, I agree that pursing biological superintelligence is a better strategy than pursuing artificial superintelligence. People inherit some of their moral values from their parents, so a superintelligent human has a reasonable probability of being a g...

Are we still talking about human beings – or optimization projects? You can’t predict or engineer how a baby will turn out. What troubles me most is how little attention is paid to emotional attachment, which is arguably the cornerstone of healthy development. This reads more like a plan for growing babies in vitro than raising actual children. Honest question: do you have kids?

Also, much of the terminology you use feels superficial or misapplied. Science and education aren’t just about memorizing buzzwords – they require deep understanding, and that takes...

Hi Nabokos,

I appreciate the comment. I think many academically inclined follks probably have similar views to yours. Let me explain my thinking here:

What troubles me most is how little attention is paid to emotional attachment, which is arguably the cornerstone of healthy development. This reads more like a plan for growing babies in vitro than raising actual children.

If I were to go into the ins and outs of emotional attachment, this already long post would have been at least twice the length. And seeing as I am not an expert in the area, I hardly think it would have been useful to the average reader.

Of course emotional attachment is important. It's one of the most important things for happy, healthy childhood development.

But there are many good books on that topic and I don't think everyone who writes about any aspect of childhood or babies needs to include a section on the topic. If you think there are good resources people here should read, please post them!

You can’t predict or engineer how a baby will turn out.

It's certainly true you can't predict EXACTLY how a baby will turn out, but you CAN influence predispositions. In fact, most of parenting is about exactly this! How to c...

On the topic of predictability and engineering – sure, we can influence predispositions, but the point I was trying to make is epistemological: the level of uncertainty and interdependence in human development makes the engineering metaphor fragile. Medicine, to your point, does aim to “figure out” complex systems – but it’s also deeply aware of its limitations, unintended consequences, and historical hubris. That humility didn’t come through strongly in your piece, at least to me.

Perhaps so. But the default assumption, seemingly made by just about everyone, is that there is nothing we can do about any of this stuff.

And that's just wrong. The human genome is not a hopeless complex web of entangled interactions. Most of the variance in common traits is linear in nature, meaning we can come up with reasonably accurate predictions of traits by simply adding up the effects of all the genes involved. And thus by extension, if we could flip enough of these genes, we could actually change people's genetic predisposition.

Furthermore, nature has given us the best dataset ever in genetics, which is billions of siblings that act as literal randomized control trials for the effect of genes ...

This is my first comment in this forum. I discovered you guys early this morning and read the posts until about 5 a.m., completely hypnotized. Considering the current context of social media, it’s been a long time since a deep read has held my attention like this. Man, this has been the most interesting post I’ve accessed so far. I feel that being part of this community and connecting with people like you will add a lot to my self-development. Congratulations on the text.

Enviado de SP BR, texto original em portugues traduzido com o uso de IA.

Interesting article! Thanks for writing. But I am suspicious of claims about increasing IQ because, if it was possible, surely someone would have done a proof-of-concept with animals.

It's difficult to do such experiments with humans because (1) ethical issues; (2) humans take 9 months to be born (long gestation period); and (3) a few years for them to mature enough to get any objective results. I imagine the effort to increase IQ would be iterative. That needs a quick feedback loop which is not possible with humans.

There must be some animal with (1) no eth...

Currently, we have smart people who are using their intelligence mainly to push capabilities. If we want to grow superbabies into humans that aren't just using their intelligence to push capabilities, it would be worth looking at which kind of personality traits might select for actually working on alignment in a productive fashion.

This might be about selecting genes that don't correlate with psychopathy but there's a potential that we can do much better than just not raising psychopaths. If you want to this project for the sake of AI safety, it would be crucial to look into what kind of personality that needs and what kind of genes are associated with that personality.

It is becoming increasingly clear that for many traits, the genetic effect sizes estimated by genetic association studies are substantially inflated for a few reasons. These include confounding due to uncontrolled population stratification, such as dynastic effects, and perhaps also genetic nurture[1]. It is also clear that traits strongly mediated through society and behaviour, such as cognitive ability, are especially strongly affected by these mechanisms.

You can avoid much of this confounding by performing GWAS on only the differences between sibl...

Very interesting read, thank you.

This post captures the tension between ethics and optimization well. The bottleneck is our emotional governance layer. Human institutions treat “fairness” as invariant even when it blocks aggregate progress. A modest right-tail IQ shift yields exponential returns in innovation density and survival probability.

Please add population‑level math to the scaling story. Using a normal model:

- ≥130: 2.28% baseline → 3.59% with +3 → 4.78% with +5 (×1.58 and ×2.10).

- ≥145: 0.135% → 0.256% → 0.383% (×1.89, ×2.84).

- ≥160: 0.00317% → 0.

Hello,

I'm a Maternal-Fetal Medicine Specialist, a "High Risk" OB/GYN. This is a very interesting post, but firmly set in the realm of bench work. There's a reason Biotech has historically over-promised and underperformed. Lab results do not correlate well with clinical results in the human model. Human fertility and development are more complicated and vastly less understood than in most any other mammalian model. Human development and pregnancy are some of the least studied areas in medicine. No one in any democratic na...

I agree with the majority of this, especially the part where we are in a race to increase our own intelligence before we destroy ourselves with AI or something else.

But I think there's something missing in your analysis.

"Genes are the piano; the microbiome is the pianist."

It’s time to admit that genes are not the blueprint for life (Feb 2024) https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00327-x - I see it's closed access now; here are some quotes.

More on the microbiome & genetics: https://humanmicrobiome.info/genetics/

Examples of how important the gut mi...

Maybe I missed this in the article itself - are there plans to make sure the superbabies are aligned and will not abuse/overpower the non-engineered peers?

Very interesting, has the vibe of technology that's at least 20 years out from really hitting (assuming ASI is later than that) (though even then maybe progress speeds up? Idk, a lot of the barriers will be regulatory and certain parts won't be able to move faster than human growth and development).

The biggest surprise to me was probably that IQ selection was already happening without much fanfare - I had thought that there would be some law on the books, especially given the culture wars around pro choice/life and current admin. Perhaps it skates by because it's rare, expensive, inconvenient, screening rather than editing, and a low boost to begin with?

We’ve increased the weight of chickens by about 40 standard deviations relative to their wild ancestors, the red junglefowl. That’s the equivalent of making a human being that is 14 feet tall

I realize this is a very trivial matter on a very interesting post, and I don't like making a habit of nitpicking. But this feels interesting for some reason. Perhaps it's just because of the disturbing chicken visuals, I don't know.

To my credit, I actually made an effort to figure out the author reached their conclusion, and I believe I did. The average ad...

I had a couple-year long obsession with evolution simulators. And that hobby convinced me, that longevity is a pretty risky thing. Most of dominant species in the simulations went extinct not because of new species emerging and conflicting, but because of longevity causing problems.

1) Reduces amount of resources available to the new generation. That increases competition, and this kind of competition is evolutionary force which encourages being a long-living line, because it is easier to accumulate experience and use it later. Creates a feedback loop...

Great write up!

Why don't you do this in a mouse first? The whole cycle from birth to phenotype, including complex reasoning (e.g. bayesian inference, causality) can take 6 months.

I'm reminded of the old Star Trek episode with the super humans that were found in cryosleep that then took over the Enterprise.

While I do agree that this could be one potential counter to AI (unless the relative speed things overwhelm) but also see a similar type of risk from the engineered humans. In that view, the program needs to be something that is widely implemented (which would also make it potentially a x-risk case itself) or we could easily find ourselves having created a ruler class that views ordinary humans as subhuman on not deserving of full...

What we need most is positive trait selection, not more IQ. Sociopathy is destroying our world and high IQ’s are not saving it. Get rid of the sociopaths and IQ may be salient.

You could also make people grow up a bit faster. Some kids are more mature, bigger, etc than others at the same wall-clock age. If this doesn't conflict with lifespan then it would allow the superbabies to be productive sooner. Wouldn't want to rob someone of their childhood entirely, but 12 years of adolescence is long enough for lots of chase tag and wrestling.

Last year you guys wrote a post on adult intelligence enhancement. Does any of your research on super babies have implications for that, especially radical enhancement?

I know many of you dream of having an IQ of 300 to become the star researcher and avoid being replaced by AI next year. But have you ever considered whether nature has actually optimized humans for staring at equations on a screen? If most people don’t excel at this, does that really indicate a flaw that needs fixing?

Moreover, how do you know that a higher IQ would lead to a better life—for the individual or for society as a whole? Some of the highest-IQ individuals today are developing technologies that even they acknowledge carry Russian-roulette odds of wiping out humanity—yet they keep working on them. Should we really be striving for more high-IQ people, or is there something else we should prioritize?

Let's say it all turned out as expected and with minimal side effects we turned 100 IQ embryos into 150 IQ super-babies. Wouldn't this guarantee that every one of those enhanced children have zero chance at a normal upbringing? If they attended school at normal ages and progressed at a normal pace they would be horribly understimulated, but by attending accelerated programs they miss out on all the socialization and key moments we get by default. Eight-year-old high school graduates won't be found at prom or getting to have an awkward crush.

Now you might s...

Perhaps it will soon be the most Effective Altruism to raise your own superbabies. You're creating the next best thing to friendly AGI, in a context where the rest of the world is neglecting this low-hanging fruit. You could shape the first generation of smarter-than-unedited-human intelligence.

Interesting analysis, though personally, I am still not convinced that companies should be able to unilaterally (and irreversibly) change/update the human genome. But, it would be interesting to see this research continue in animals. E.g.

Provide evidence that they've made a "150 IQ" mouse or dog. What would a dog that's 50% smarter than the average dog behave like? or 500% smarter? Would a dog that's 10000% smarter than the average dog be able to learn, understand and "speak" in human languages?

Create 100s generations of these ...

You can’t just threaten the life and livelihood of 8 billion people and not expect pushback.

"Can't" seems pretty strong here, as apparently you can... at least, so far...

Definitely "shouldn't" though...

If genetic editing technology is first used by the wealthy, it may further exacerbate social inequality. This technology could be used to create a “super elite,” thereby further solidifying social stratification. The scenario of a “superbaby oligarchy” mentioned in the article is a worrying potential future.

@momom2 mentioned that there didn't seem to be anyone else in the comment section with a "kill it with fire" reaction. I don't think killing it with fire is the right approach either, but this research should be taken slow. I do not see a near future where superbaby injections aren't made prohibitively expensive, creating a new race of super-oligarchs. I think many of those hesitant researchers mentioned in the beginning of the article also see that future, which is probably why they aren't too excited to discuss those applications of their research.

We don’t actually know that JK He accomplished what he said he did. He may have tried. But the results have not been independently verified. That would require genotyping the parents and children. So, premature to say that germline editing appears safe in humans.

You might not be tracking that there's a "unilateralist cloud" of behaviors. There's the norm of behavior, and then around that norm, there's a cloud of variation. The most extreme people (the unilateralist frontier) will do riskier things than the norm, and bad stuff will result. If a unilateralist doing unilateral stuff results in a deformed baby, or even of a legit prospective risk of a deformed baby (as you acknowledge existed in He Jiankui's experiments), that's bad. If society sees this happen, it means that their current norm is not conservative enough to keep the unilateralist frontier in the safe zone. So they adjust the norm to be more conservative.

When you write

This method has actually been used in human embryos before! In 2018 Chinese scientist He Jiankui created the first ever gene edited embryos by using this technique. All three of the children born from these embryos are healthy 6 years later (despite widespread outrage and condemnation at the time).

it sounds like you're implying that the outrage and condemnation were a claim that the experiment would actually have bad results. Which, surely to some extent they were. But also they were (legit, as you agree!) a c...

This is a really interesting article and I commend the author for broaching the topic and proposing a way of getting around this stigmatization in the field. After diseases though i think an even greater priority than increasing IQ or lifespan is tackling what may seem to be a really trivial matter. And that is the issue of skin lightening. Though this may seem like a trivial topic I would say that conservatively tens of millions of mostly women possibly even hundreds of Millions in africa, asia, and the Middle East are literally poisoning and disfiguring ...

At one point in the text, it was mentioned that any ethical counterargument is not enough to demonize genome editing. Personally, I don’t see any issues with positive changes, but discussing this solely from the perspective of genetic science, without considering social science and all the people who already exist, is irresponsible. If the project receives the multimillion-dollar investment it needs and develops in the most efficient way possible, would the idea be to mass-produce gifted individuals until people born the traditional way are replaced? Maybe...

Thanks for the post! I think genetic engineering for increasing IQ can indeed be super valuable, and is quite neglected in society. However, I would be very surprised if it was among the areas where additional investment generates the most welfare per $:

- Open Philanthropy (OP) estimated that funding R&D (research and development) is 45 % as cost-effective as giving cash to people with 500 $/year.

- People in extreme poverty have around 500 $/year, and unconditional cash transfer to them are like 1/3 as cost-effective as GiveWell's (GW's) top charities. GW

While I think finding ways to make future generations healthier and smarter is a worthy goal, I don't think we understand enough yet to do this without potentially severe unintended consequences, and I wouldn't consider doing it myself with our current technology. It's a good bet that many of the seemingly deleterious mutations we'd like to eliminate also offer some benefit we don't understand- given that we have already discovered many instances of mutations with apparent intelligence/health tradeoffs, and disease resistance/health tradeoffs. If you're se...

Very not important question: is Gene Smith your actual name or a pseudonymn?

Either way, it's the perfect name for the author of this post.

Hats off to you gene smith.

EDIT: Read a summary of this post on Twitter

Working in the field of genetics is a bizarre experience. No one seems to be interested in the most interesting applications of their research.

We’ve spent the better part of the last two decades unravelling exactly how the human genome works and which specific letter changes in our DNA affect things like diabetes risk or college graduation rates. Our knowledge has advanced to the point where, if we had a safe and reliable means of modifying genes in embryos, we could literally create superbabies. Children that would live multiple decades longer than their non-engineered peers, have the raw intellectual horsepower to do Nobel prize worthy scientific research, and very rarely suffer from depression or other mental health disorders.

The scientific establishment, however, seems to not have gotten the memo. If you suggest we engineer the genes of future generations to make their lives better, they will often make some frightened noises, mention “ethical issues” without ever clarifying what they mean, or abruptly change the subject. It’s as if humanity invented electricity and decided the only interesting thing to do with it was make washing machines.

I didn’t understand just how dysfunctional things were until I attended a conference on polygenic embryo screening in late 2023. I remember sitting through three days of talks at a hotel in Boston, watching prominent tenured professors in the field of genetics take turns misrepresenting their own data and denouncing attempts to make children healthier through genetic screening. It is difficult to convey the actual level of insanity if you haven’t seen it yourself.

As a direct consequence, there is low-hanging fruit absolutely everywhere. You can literally do novel groundbreaking research on germline engineering as an internet weirdo with an obsession and sufficient time on your hands. The scientific establishment is too busy with their washing machines to think about light bulbs or computers.

This blog post is the culmination of a few months of research by myself and my cofounder into the lightbulbs and computers of genetics: how to do large scale, heritable editing of the human genome to improve everything from diabetes risk to intelligence. I will summarize the current state of our knowledge and lay out a technical roadmap examining how the remaining barriers might be overcome.

We’ll begin with the topic of the insane conference in Boston; embryo selection.

How to make (slightly) superbabies

Two years ago, a stealth mode startup called Heliospect began quietly offering parents the ability to have genetically optimized children.

The proposition was fairly simple; if you and your spouse went through IVF and produced a bunch of embryos, Heliospect could perform a kind of genetic fortune-telling.

They could show you each embryo’s risk of diabetes. They could tell you how likely each one was to drop out of high school. They could even tell you how smart each of them was likely to be.

After reading each embryo's genome and ranking them according to the importance of each of these traits, the best would be implanted in the mother. If all went well, 9 months later a baby would pop out that has a slight genetic advantage relative to its counterfactual siblings.

The service wasn’t perfect; Heliospect’s tests could give you a rough idea of each embryo’s genetic predispositions, but nothing more.

Still, this was enough to increase your future child’s IQ by around 3-7 points or increase their quality adjusted life expectancy by about 1-4 years. And though Heliospect wasn’t the first company to offer embryo selection to reduce disease risk, they were the first to offer selection specifically for enhancement.

The curious among you might wonder why the expected gain from this service is “3-7 IQ points”. Why not more? And why the range?

There are a few variables impacting the expected benefit, but the biggest is the number of embryos available to choose from.

Each embryo has a different genome, and thus different genetic predispositions. Sometimes during the process of sperm and egg formation, one of the embryos will get lucky and a lot of the genes that increase IQ will end up in the same embryo.

The more embryos, the better the best one will be in expectation. There is a “scaling law” describing how good you can expect the best embryo to be based on how many embryos you’ve produced.

With two embryos, the best one would have an expected IQ about 2 points above parental average. WIth 10 the best would be about 6 points better.

But the gains plateau quickly after that. 100 embryos would give a gain of 10.5 points, and 200 just 11.5.

If you graph IQ gain as a function of the number of embryos available, it pretty quickly becomes clear that we simply aren’t going to make any superbabies by increasing the number of embryos we choose from.

The line goes nearly flat after ~40 or so. If we really want to unlock the potential of the human genome, we need a better technique.

How to do better than embryo selection

When we select embryos, it’s a bit like flipping coins and hoping most of them land on heads. Even if you do this a few dozen times, your best run won’t have that many more heads than tails.

If we could somehow directly intervene to make some coins land on heads, we could get far, far better results.

The situation with genes is highly analogous; if we could swap out a bunch of the variants that increase cancer risk for ones that decrease cancer risk, we could do much better than embryo selection.

Gene editing is the perfect tool to make this happen. It lets us make highly specific changes at known locations in the genome where simple changes like swapping one base pair for another is known to have some positive effect.

Let’s look again at the IQ gain graph from embryo selection and compare it with what could be achieved by editing using currently available data.

See the appendix for a full description of how this graph was generated and the assumptions we make.

If we had 500 embryos, the best one would have an IQ about 12 points above that of the parents. If we could make 500 gene edits, an embryo would have an IQ about 50 points higher than that of the parents.

Gene editing scales much, much better than embryo selection.

Some of you might be looking at the data above and wondering “well what baseline are we talking about? Are we talking about a 60 IQ point gain for someone with a starting IQ of 70?”

The answer is the expected gain is almost unaffected by the starting IQ. The human gene pool has so much untapped genetic potential that even the genome of a very, very smart person still has thousands of IQ decreasing variants that could potentially be altered.

What’s even crazier is this is just the lower bound on what we could achieve. We haven’t even used all the data we could for fine-mapping, and if any of the dozen or so biobanks out there decides to make an effort to collect more IQ phenotypes the expected gain would more than double.

Like machine learning, gene editing has scaling laws. With more data, you can get a larger improvement out of the same number of edits. And with a sufficiently large amount of data, the benefit of gene editing is unbelievably powerful.

Already with just 300 edits and a million genomes with matching IQ scores, we could make someone with a higher predisposition towards genius than anyone that has ever lived.

This won’t guarantee such an individual would be a genius; there are in fact many people with exceptionally high IQs who don’t end up making nobel prize worthy discoveries.

But it will significantly increase the chances; Nobel prize winners (especially those in math and sciences) tend to have IQs significantly above the population average.

It will make sense to be cautious about pushing beyond the limit of naturally occurring genomes since data about the side-effects of editing at such extremes is quite limited. We know from the last few millennia of selective breeding in agriculture and husbandry that it’s possible to push tens of standard deviations beyond any naturally occurring genome (more on this later), but animal breeders have the advantage of many generations of validation over which to refine their selection techniques. For the first generation of enhanced humans, we’ll want to be at least somewhat conservative, meaning we probably don’t want to push much outside the bounds of natural human variation.

Maximum human life expectancy

Perhaps even more than intelligence, health is a near universal human good. An obvious question when discussing the potential of gene editing is how large of an impact we could have on disease risk or longevity if we edited to improve them.

The size of reduction we could get from editing varies substantially by disease. Some conditions, like coronary artery disease and diabetes, can be nearly eliminated with just a handful of edits.

Others, like stroke and depression take far more edits and can’t be targeted quite as effectively.

You might wonder why there’s such a large difference between conditions. Perhaps this is a function of how heritable these diseases are. But that turns out to be only part of the story.

The other part is the effect size of common variants. Some diseases have several variants that are both common among the population and have huge effect sizes.

And the effect we can have on them with editing is incredible. Diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, Alzheimer’s, and multiple sclerosis can be virtually eliminated with less than a dozen changes to the genome.

Interestingly, a large proportion of conditions with this property of being highly editable are autoimmune diseases. Anyone who knows a bit about human evolution over the last ten thousand years should not be too surprised by this; there has been incredibly strong selection pressure on the human immune system during that time. Millenia of plagues have made genetic regions encoding portions of the human immune system the single most genetically diverse and highly selected regions in the human genome.

As a result the genome is enriched for “wartime variants”; those that might save your life if the bubonic plague reemerges, but will mess you up in “peacetime” by giving you a horrible autoimmune condition.

This is, not coincidentally, one reason to not go completely crazy selecting against risk of autoimmune diseases: we don't want to make ourselves that much more vulnerable to once-per-century plagues. We know for a fact that some of the variants that increase their risk were protective against ancient plagues like the black death (see the appendix for a fuller discussion of this).

With most trait-affecting genetic variants, we can make any trade-offs explicit; if some of the genetic variants that reduce the risk of hypertension increase the risk of gallstones, you can explicitly quantify the tradeoff.

Not so with immune variants that protect against once-per-century plagues. I dig more into how to deal with this tradeoff in the appendix but the TL;DR is that you don’t want to “minimize” risk of autoimmune conditions. You just want to reduce their risk to a reasonable level while maintaining as much genetic diversity as possible.

Is everything a tradeoff?

A skeptical reader might finish the above section and conclude that any gene editing, no matter how benign, will carry serious tradeoffs.

I do not believe this to be the case. Though there is of course some risk of unintended side-effects (and we have particular reason to be cautious about this for autoimmune conditions), this is not a fully general counterargument to genetic engineering.

To start with, one can simply look at humans and ask “is genetic privilege a real thing?”

And the answer to anyone with eyes is obviously “yes”. Some people are born with the potential to be brilliant. Some people are very attractive. Some people can live well into their 90s while smoking cigarettes and eating junk food. Some people can sleep 4 hours a night for decades with no ill effects.

And this isn’t just some environmentally induced superpower either. If a parent has one of these advantages, their children are significantly more likely than a stranger to share it. So it is obvious that we could improve many things just by giving people genes closer to those of the most genetically privileged.

But there is evidence from animal breeding that we can go substantially farther than the upper end of the human range when it comes to genetic engineering.

Take chickens. While literally no one would enjoy living the life of a modern broiler chicken, it is undeniable that we have been extremely successful in modifying them for human needs.

We’ve increased the weight of chickens by about 40 standard deviations relative to their wild ancestors, the red junglefowl. That’s the equivalent of making a human being that is 14 feet tall; an absurd amount of change. And these changes in chickens are mostly NOT the result of new mutations, but rather the result of getting all the big chicken genes into a single chicken.

Some of you might point out that modern chickens are not especially healthy. And that’s true! But it’s the result of a conscious choice on the part of breeders who only care about health to the extent that it matters for productivity. The health/productivity tradeoff preferences are much, much different for humans.

So unless the genetic architecture of human traits is fundamentally different from those of cows, chickens, and all other domesticated animals (and we have strong evidence this is not the case), we should in fact be able to substantially impact human traits in desirable ways and to (eventually) push human health and abilities to far beyond their naturally occurring levels.