A friend has spent the last three years hounding me about seed oils. Every time I thought I was safe, he’d wait a couple months and renew his attack:

“When are you going to write about seed oils?”

“Did you know that seed oils are why there’s so much {obesity, heart disease, diabetes, inflammation, cancer, dementia}?”

“Why did you write about {meth, the death penalty, consciousness, nukes, ethylene, abortion, AI, aliens, colonoscopies, Tunnel Man, Bourdieu, Assange} when you could have written about seed oils?”

“Isn’t it time to quit your silly navel-gazing and use your weird obsessive personality to make a dent in the world—by writing about seed oils?”

He’d often send screenshots of people reminding each other that Corn Oil is Murder and that it’s critical that we overturn our lives to eliminate soybean/canola/sunflower/peanut oil and replace them with butter/lard/coconut/avocado/palm oil.

This confused me, because on my internet, no one cares. Few have heard of these theories and those that have mostly think they’re kooky. When I looked for evidence that seed oils were bad, I’d find people with long lists of papers. Those papers each seemed vaguely concerning, but I couldn’t find any “reputable” sources that said seed oils were bad. This made it hard for me to take the idea seriously.

But my friend kept asking. He even brought up the idea of paying me, before recoiling in horror at my suggested rate. But now I appear to be writing about seed oils for free. So I guess that works?

On seed oil theory

There is no one seed oil theory.

I can’t emphasize this enough: There is no clear “best” argument for why seed oils are supposed to be bad. This stuff is coming from internet randos (♡) who differ both in what they think is true, and why they think it. But we can examine some common arguments.

We ate seed oil and we got fat.

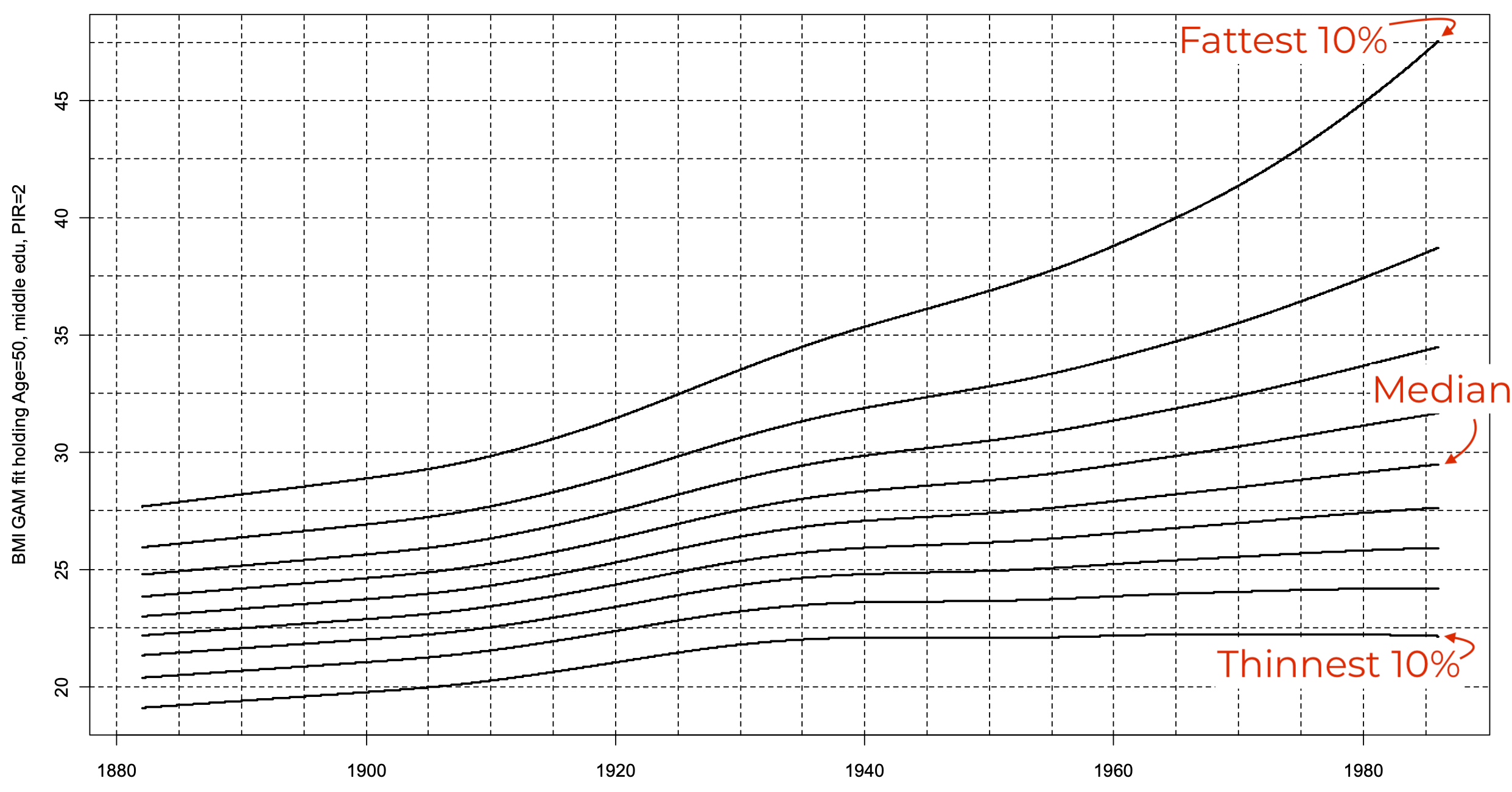

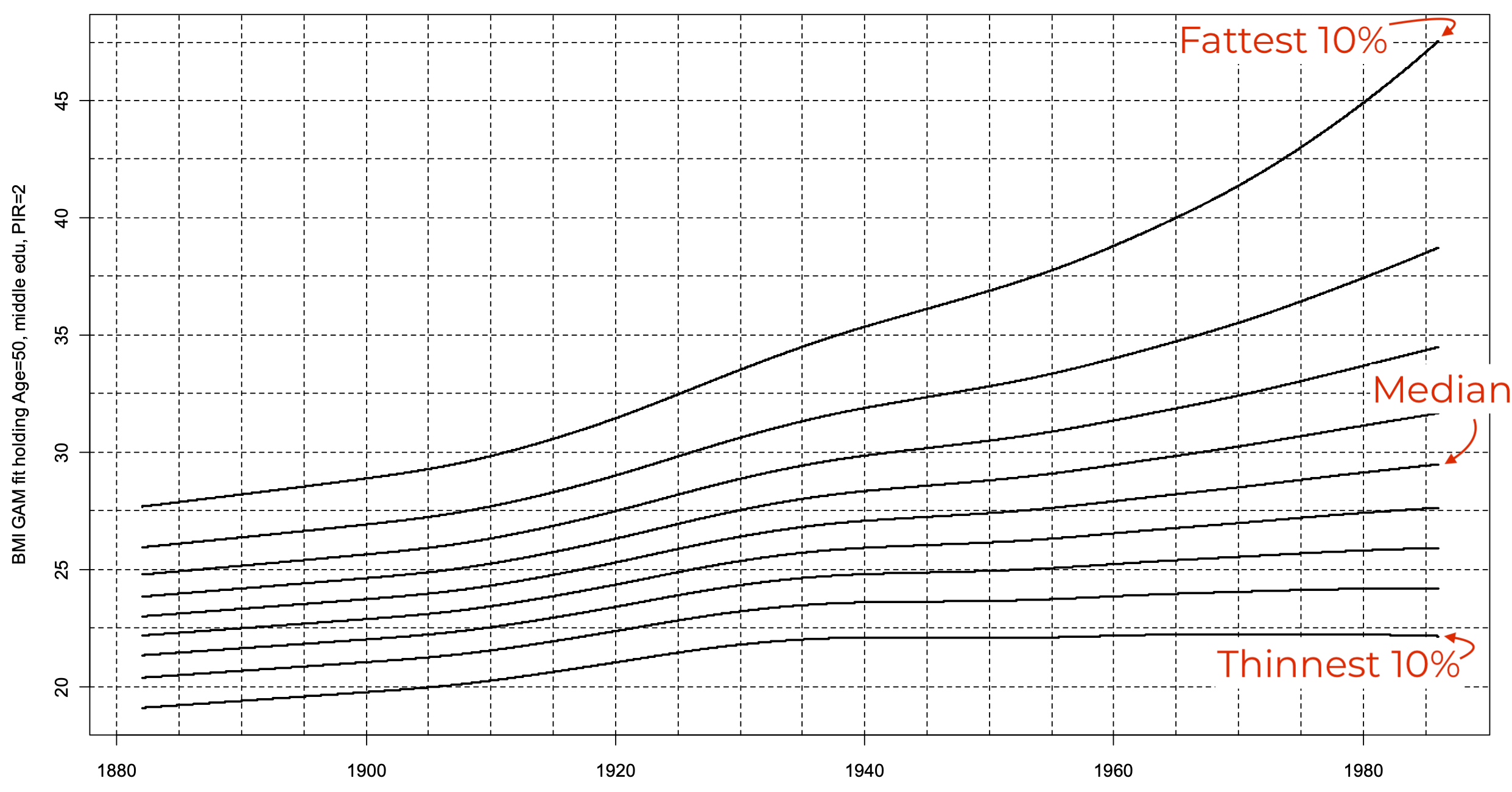

One argument is that for most of human history, nobody dieted and everyone was lean. But some time after the industrial revolution, people in Western countries started gaining weight and things have accelerated ever since. Here’s BMI at age 50 for white, high-school educated American men born in various years:

For the last few decades, obesity (BMI ≥30) has grown at around 0.6% per year. Clearly we are doing something wrong. We evolved to effortlessly stay at a healthy weight, but we’ve somehow broken our regulatory mechanisms. Anywhere people adopt a Western diet, the same thing happens.

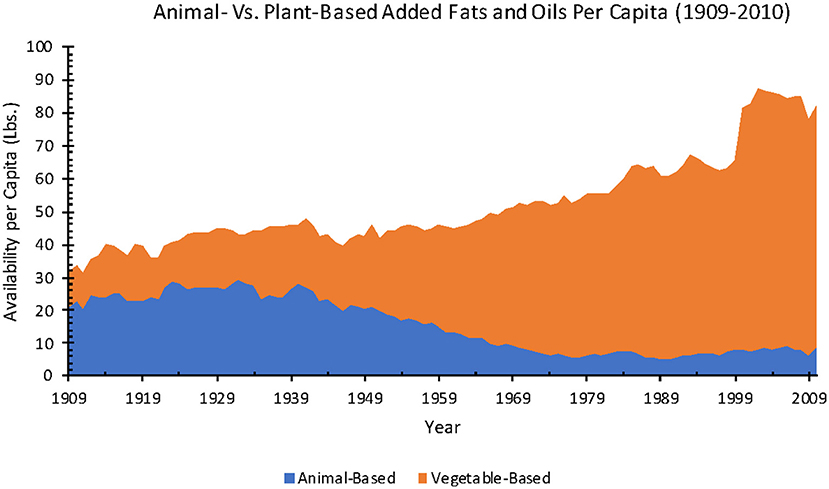

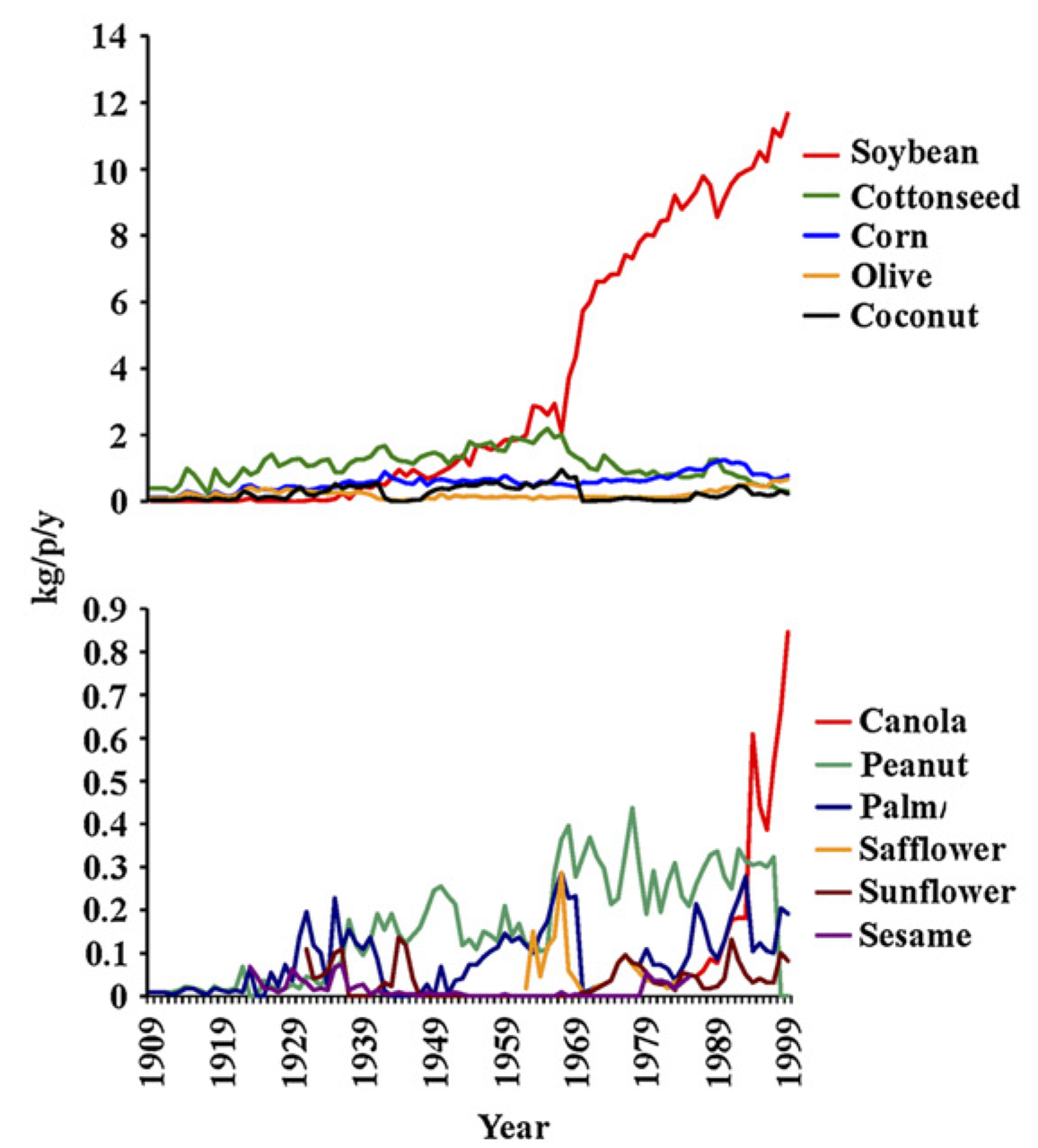

Of course, the Western diet is many things. But if you start reading ingredients lists, you’ll soon notice that everything has vegetable oil in it. Anything fried, obviously, but also instant noodles, chips, crackers, tortillas, cereal, energy bars, canned tuna, processed meats, plant-based meat, coffee creamer, broths, frozen dinners, salad dressing, and sauces. Also: Baby food, infant formula, and sometimes even ice cream or bread. People eat a lot more vegetable oil than they used to (figure from Lee et al. (2022)):

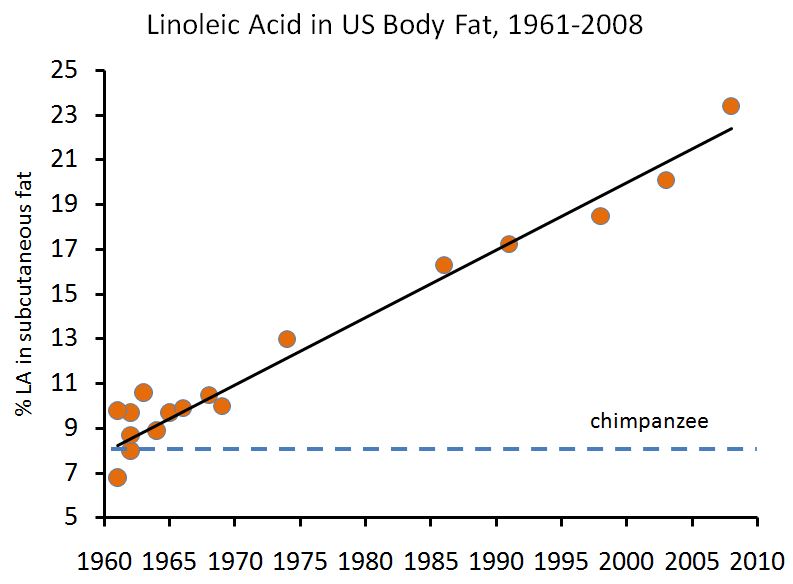

Many vegetable oils (and particularly seed oils) are high in linoleic acid. And guess what’s making up a rapidly increasing fraction of body fat? (figure from Stephan Guyenet):

Even many types of meat now have high linoleic acid levels, because the animals are now eating so much vegetable oil. It’s plausible this is doing something to us.

And seed oils are highly processed.

Another common argument is that even if we can’t identify exactly where the Western diet went wrong, we know that we spent almost our whole evolutionary history eating like hunter-gatherers (and most of the rest eating like subsistence farmers). And hunter-gatherers are all thin. So maybe we should eat like they did?

That sounds kind of fanciful, but consider the most conventional dietary advice, the thing that every expert screams every time they have a chance—AVOID PROCESSED FOOD.

The USDA defines processing as:

washing, cleaning, milling, cutting, chopping, heating, pasteurizing, blanching, cooking, canning, freezing, drying, dehydrating, mixing, or other procedures that alter the food from its natural state. This may include the addition of other ingredients to the food, such as preservatives, flavors, nutrients and other food additives or substances approved for use in food products, such as salt, sugars and fats.

Basically, don’t do… anything? That sounds awfully similar to eating like a hunter-gatherer. It’s unclear why many of these types of processing would be harmful. (Cooking? Washing?) But maybe that’s smart—maybe biology and nutrition are so complicated that we shouldn’t even try to understand them.

Traditional oils involve some processing, but they’re pretty easy. To make butter, you milk a cow and churn the milk. To make olive oil, you grind some olives and press them. To make lard, you take a beautiful pig with hopes and dreams, you kill it, you cut off the fattiest bits, and then you boil them and strain.

But here’s how you make canola oil: Take rapeseeds, put them through a vibrating sieve, then a roller mill, then a screw press, then do a hexane extraction, then do a sodium hydroxide wash in a centrifuge, then cool and filter out wax, then pass through bleaching clay, then do a steam injection in a vacuum. Whatever comes out of this is not something your DNA anticipates.

And some studies say seed oils are bad.

Another argument is that seed oils are bad experimentally. Even if you don’t understand how nutrition works, you can still try stuff—e.g. you can have people replace animal fat (or saturated fat) with vegetable oil (or unsaturated fat) and see if this makes them healthier. Usually, such trials were done with the expectation that they’d show vegetable oils were healthier. And often they do. But in a couple cases—notably the Sydney Diet Heart Study, and the Minnesota Coronary Survey—the groups with more vegetable oil did worse, not better.

And there are plausible mechanisms.

Our last argument is that we know how seed oils hurt you. People seem to suggest five possible mechanisms:

- Maybe linoleic acid (common in seed oils) is metabolized into arachidonic acid, and thereby causes inflammation.

- Maybe linoleic acid becomes oxidized LDL and thereby causes inflammation.

- Maybe it’s the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fats you eat that matters.

- Maybe vegetable oil doesn’t make you feel full like animal fats do, meaning vegetable oils lead to overeating.

- Maybe vegetable oils have an increased propensity to become trans fats.

On fat

There are many kinds of fat.

When first trying to make sense of these arguments, I encountered terms like “cis medium-chain omega-7 polyunsaturated fat”, which left me confused and terrified. (Biochemistry’s enormity has always had a way of making me feel insignificant.) After looking into things, I’m still quite scared, but at least I’ve made the Dynomight Fatty Acid Classifier.

Fat is made of fatty acids—chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms linked together with a couple oxygen atoms near the end. Usually, these are “single” bonds. But sometimes there are “double” bonds, which are very important because they are easier to break apart. So different fatty acids are categorized mostly based on the double bonds. So, behold:

If you want, you can further divide things up in terms of the length of the fatty acid, or even count how many single bonds there are between each double bond.

Different oils have different fats.

Here’s a picture (simplified from Mikael Häggström’s version):

Animal fat tends to be high in saturated and monounsaturated fat while vegetable oil tends to be high in polyunsaturated fat. But there are a few notable exceptions (not all listed above):

- Olive oil, canola oil, and avocado oil are high in monounsaturated fat.

- Coconut oil is high in saturated fat.

- Palm oil has both saturated and monounsaturated fat, but little polyunsaturated fat.

Of course, you can also break things down into different subcategories of fats or even individual fatty acids.

Trans fat is bad.

The double bonds in fatty acids have two possible configurations. They can be “normal” (cis) or they can be “reversed” in a way that leaves the rest of the fatty acid chain “flipped” (trans). (The Dynomight Biologist howls in protest at this description, but is overruled.)

Starting around 100 years ago, people noticed you could “hydrogenate” unsaturated fats by heating them and cramming in extra hydrogen atoms. If this is done completely, it will transform all the double bonds into single bonds, changing the unsaturated fat into saturated fat. This gives something similar to lard, but cheaper. You probably eat hydrogenated vegetable oils all the time—they’re used for “shortening” and are in icing and all sorts of baked and fried foods.

But if you don’t fully hydrogenate the oil you end up with—you guessed it—partially hydrogenated oil, in which many of the natural cis bonds will be converted to trans bonds. Partially hydrogenated oils are cheap, have high shelf lives, and can easily be made in a range of consistencies.

That’s a shame because trans fats are pretty rare in nature (maybe 3% of butter/canola oil, around 0.5% of olive oil) and evolution doesn’t seem to have prepared us to eat large amounts of them. The WHO calls them “deadly”. It’s consensus that they cause obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, though the mechanism of harm often still isn’t understood. Trans fats started being phased out around the world about 25 years ago. But before that happened, they were estimated to cause 30k to 100k deaths per year in the United States.

So, don’t eat trans fats.

About that, bad news—if you cook with unsaturated fat at high temperature you can make your own trans fats right in your kitchen. Though it seems like not much happens if you stay below 200℃, and even with high temperatures and long times, it’s hard to get above 8%. Still, deep-frying with the same oil for days on end seems like a bad idea.

And a note for Americans: If your food has less than 0.5 grams of trans fats per serving, then it can legally be labeled as having “zero” trans fat. Cooking oils typically have a serving size of a tablespoon (14g), meaning that the “zero trans fat” threshold is around 3.6% trans fat. Companies apparently respond to this by diluting their trans-fat-containing products with regular vegetable oil just enough to get down to 3.6%. Ain’t capitalism grand?

Anyway, trans fats seem like a good lesson about unintended consequences and how we should be careful about screwing around with what we eat.

Trans fats are also sometimes suggested as a reason that animal fats might be healthier than vegetable fats: Animal fats are mostly saturated fat, and saturated fat cannot become trans because it has no double bonds.

The outside view

Much of this is plausible.

There’s lots to like about seed oil theory. I’m sympathetic to the idea that the modern Western diet is somehow fundamentally broken. (Look at what’s happening to us!) Even if we don’t understand exactly why, it looks like “processing” is bad, and seed oils sure are processed.

The suggested mechanisms for seed oils to be harmful seem plausible, too. I could believe that omega-6 fats cause oxidization or inflammation or that saturated fats might make you feel more full. Experts seem to agree that most people should eat more omega-3 fats.

And if you want a monocausal story for every modern health problem, inflammation is a good mechanism. We have other cases where one source of inflammation causes a range of seemingly unrelated health problems (e.g. air pollution).

Finally, seed oil theorists often suggest replacing unsaturated fat with saturated fat. This conflicts with the old consensus that saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease. But there seems to be increasing doubt about that old consensus (Astrup et al. 2020). Many still defend it, but there’s real debate.

So that’s good. But there are also reasons for doubt.

But correlation ⇏ causation.

Just because two things happened at the same time doesn’t mean one caused the other. Maybe there’s some causal relationship, or maybe it’s just random. Let’s not belabor this.

And it’s a complex mechanistic argument.

Yes, there are plausible mechanisms for seed oils to hurt us. I agree! But complex mechanistic arguments for diet do not have a good track record. So far they’ve worked for… basically nothing? (We’re still debating if eating salt or cholesterol are bad for you.)

When humans build complex systems, we modularize, so we can understand what’s happening. But evolution is a lunatic. It doesn’t care about understanding. So biological systems tend to be spectacularly non-modularized. When I started reading Molecular Biology of the Cell I almost felt like I wanted to throw up, what with all the exceptions to the exceptions to the exceptions.

Did you know that dogs sneeze to signal they’re feeling playful? I guess this happened because evolution wanted a way to signal playfulness, so why not just use an existing instinct for expelling particles? It’s a little confusing, but no big deal, right? Our bodies are a collection of millions of these kinds of hacks stacked on top of each other.

Maybe the mechanisms people give for seed oils are right. I’m no expert, and I’ve exhausted the patience of everyone I know who is. But there are 8 billion other interacting mechanisms. Above all, I don’t understand why seed oil theorists are so damned confident. It’s fine to speculate about mechanisms, but you do that for choosing what to investigate experimentally, not as a final source of truth.

And seed oil theories have features that make them hard to falsify.

For example:

- There are many variants of these theories. Is it all vegetable oil that’s bad, or just seed oil? Is olive oil OK? Or is it unsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, omega-6 fat, or just linoleic acid? Is it the omega-6:3 ratio, and if so then why avoid canola oil with its extremely low ratio? People who criticize one theory are often told they aren’t arguing against the One True seed oil theory. But what is that?

- Say some study gives some people more seed oil, and those people are fine. Is that evidence against seed oil theory? Some say no, because the harms of seed oil are nonlinear—they mostly hurt you when you cross over some threshold. If people were already past that threshold before the study started, then adding additional seed oil wouldn’t do more harm.

- Or say you reduce seed oils and don’t get healthier. Evidence against seed oil theory? Again, some say no, because you can’t “un-ring the bell”. When you eat seed oils, you cause your body to get dis-regulated. But fixing your diet won’t make you well-regulated again, because the damage is done.

- People often report switching seed oils out for saturated fats and failing to lose weight. A common response is they should look at waistline size, not total weight.

- Say some trial shows that reducing sugar has a big effect. That might suggest that seed oils aren’t everything. But some just see this as further proof of seed oil’s primacy—it’s because of seed oil that the sugar is able to do harm.

All of these things are possible. Maybe an invisible dragon really does live in your garage. But the more such features a theory has, the less I trust it.

Some seed oil theorists are selling stuff.

Some of the big seed oil theorists run companies that sell seed-oil free products. I guess this is a conflict of interest, but… if you thought seed oils were killing everyone, wouldn’t you want to help provide alternatives? I’m more worried about the internet’s usual trick of corrupting everything by showering attention on the overconfident.

The inside view

Human RCTs mostly say saturated fat is bad.

If you replace butter with seed oil, what happens? The best way to answer this question is to try it. Fortunately, many trials have been done. I stress: many. In such cases, we shouldn’t stress about individual results because anything can happen in one trial, from p-hacking to fraud to contaminated coconut oil.

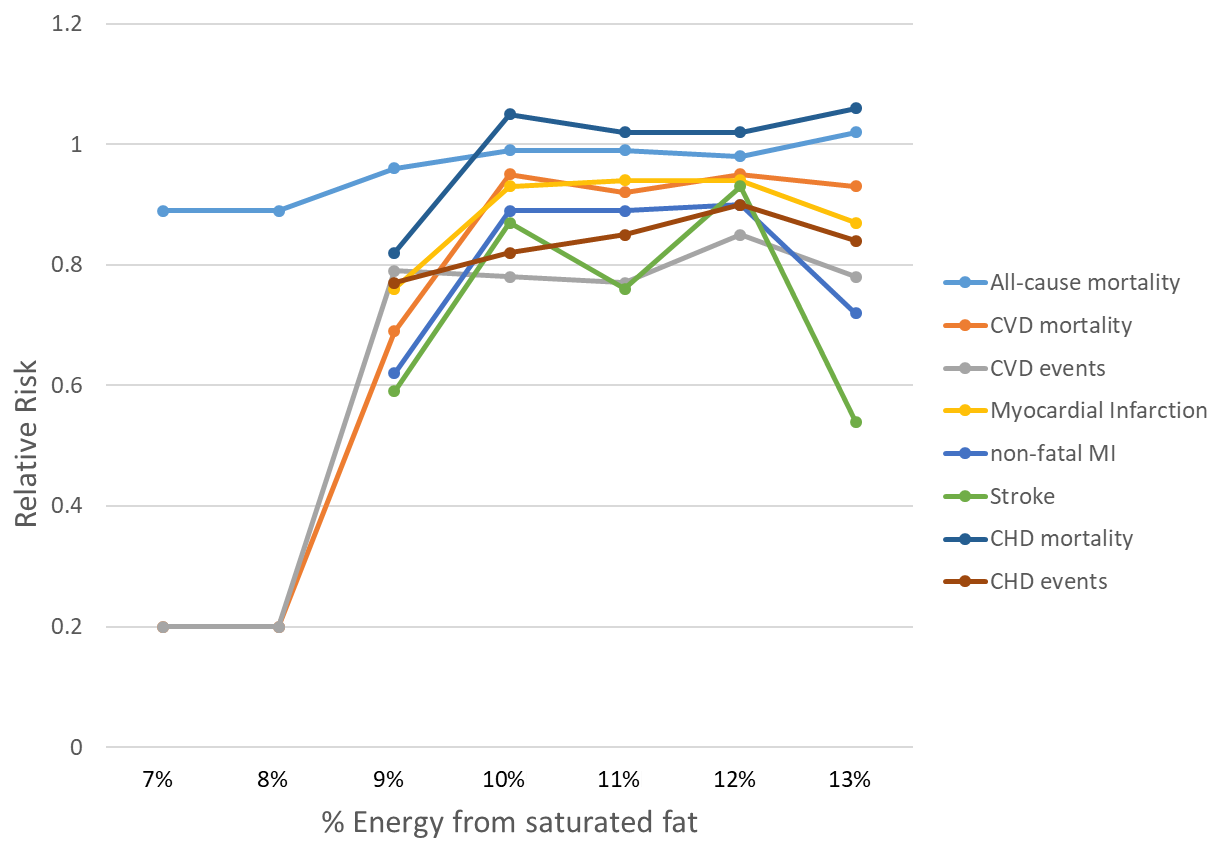

The thing to do is look at trials as a whole. Ideally, using a standard methodology. Enter Hooper et al. (2020), who did a honking meta-analysis of randomized trials in which saturated fat was reduced as part of the (highly respected) Cochrane project. They found that getting more of your overall energy from saturated fat was bad:

In more detail, they found that the groups that got less saturated fat:

- Had a 21% reduction in cardiovascular events.

- Had small (3-6%) non-statistically significant reductions in overall mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cancer.

- Had cholesterol that looked slightly better by most measures.

- Were an average of 1.8 kg (4 lb) lighter.

- Had no apparent change in cancer mortality, diabetes, or blood pressure.

This seemed to be true regardless of if saturated fat was replaced with polyunsaturated fat or carbohydrates. (There were few trials where it was replaced with monounsaturated fats or protein.)

These meta-analyses are our most important information. Averaged over decades of studies, replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats (i.e. replacing butter with seed oil) seems to be good for you, not bad for you.

I don’t see this as conclusive, or even close to conclusive. We really need more, bigger, better trials. But at the moment, the experimental evidence suggests vegetable oil is good, not bad.

There’s no conspiracy against the Sydney Diet Heart Study.

The Sydney Diet Heart Study study ran from 1966 to 1973. In it, 458 middle-aged men with a recent coronary event were randomized to either continue their normal diet or to substitute safflower (seed) oil for saturated fat. The group with the extra seed oil had lower cholesterol, but did worse both in terms of all-cause mortality, and cardiovascular disease.

Seed oil theorists talk about this trial a lot. It was a good trial! And the results aren’t good for seed oil. But it is included in the meta-analysis. Look:

In analysis after analysis, it’s sitting there, being taken into account. Along with all the other studies, which mostly don’t support the same conclusion. The Nutrivore points out that the vegetable oil group got Miracle brand margarine which was high in trans fats. That could explain their poor results, but the other group was surely eating some trans fats too, and this kind of single-trial nitpicking makes me nervous.

There’s no conspiracy against the Minnesota Coronary Survey either.

The Minnesota Coronary Survey ran from 1968 to 1973. There’s a story floating around that goes something like this: This was a huge trial with 9,423 subjects in nursing homes and mental hospitals. For the experimental group, they replaced saturated fat with vegetable oil rich in lionleic acid. They expected this to decrease heart disease, but when the opposite happened, the investigators just kind of dropped things. These “inconvenient” results were mostly ignored until 43 years later, when Ramsden et al. (2016) came around and recovered the old data.

When I read this story I was pumping my fist. Fixing publication bias by scrounging up lost data from decades ago! Yes! But when I looked into the details, that story is mostly bogus. The main results of this trial have been available for decades. Here is Figure 6 from Frantz et al. (1989), which clearly shows that the control group does a bit better:

Some say that even if the results were published, they were ignored before Ramsden et al., but that’s not true either. Check the citations if you want—most come before 2016.

Now, this study is not in the meta-analysis. They excluded it because there were high dropout rates, meaning the average subject was only in the trial for only one year. It was also very weird by modern standards—they created fake meat and cheese where the natural fats were replaced with vegetable oil. (There’s a whole sub-debate about if that vegetable oil contained trans fat. We’ll probably never know because the records are lost and no one who might remember is still alive.)

The exclusion of this study is no conspiracy. Lots of trials where vegetable oils look great were also excluded. For example, the legendary Finnish Mental Hospital trial ran for 12 years and found that a similar (also weird) diet reduced heart disease by almost 50% and overall mortality by 11%. It was excluded because it used a crossover design rather than randomization.

If you want different inclusion criteria, fine! Argue that your criteria are better, and do a new meta-analysis. But ad-hoc inclusion and exclusion of individual studies is a recipe for getting answers that fit with your preconceptions. Just look at the track record of using polling data to predict elections.

Public health authorities mostly say saturated fat is bad.

I’ve seen people claim that public health authorities in “other countries” support substituting saturated fats for unsaturated fats. This, for the record, is untrue. I looked up the official advice of all the G7 countries plus the WHO, Spain and Australia:

| Country | Total Fat | Saturated Fat | Vegetable oil | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO | Limit | Limit | Prefer | |

| United States | Limit | Prefer | ||

| Germany | Limit | Prefer | ||

| UK | Limit | Limit | Prefer | |

| France | Limit | Limit | Eat more α-LA good | |

| Italy | Limit | Limit | Prefer | Limit heat for unsaturated fats |

| Spain | Limit | Prefer | Olive oil good | |

| Canada | Limit | Prefer | Limit palm/coconut oil | |

| Australia | Limit | Prefer | ||

| Japan | Limit | “Enjoy your meals” |

Seed oil folks often bring up the French paradox, the (controversial) claim that French people are/were thin and have low cardiovascular disease despite eating lots of saturated-fat-rich croissants or whatever. And I guess France comes closest to the seed oil position, since they don’t endorse vegetable oils and suggest increasing α-LA, an omega-3 fat. But France still says to limit saturated fat. Japan seems focused on other things.

Seed oils don’t seem to cause inflammation.

The most comprehensive meta-review I could find (Johnson and Fritsche, 2012) looked at trials that increased linoleic acid or omega-6 fats (basically, seed oils). It found that “virtually no data” existed to support the idea that this increased inflammation.

Beyond that, the suggested “LA → AA” mechanism seems to be basically disproven. The problem is that metabolism of linoleic acid (LA) into arachidonic acid (AA) saturates at low levels of LA consumption (Liou and Innis 2009). A meta-review (Rett and Whelan, 2011) found that many different trials that decreased LA by up to 90% or increased it by up to 600% all seemed to do basically nothing:

It’s not clear if the timelines work out.

True, seed oil consumption has skyrocketed along with obesity. But hold on. If seed oil consumption is causing obesity, then people should have started getting fat after seed oils started increasing. Did they?

Blasbalg et al. (2011) give some long-term estimates of vegetable oil consumption: (Note the scale is smaller in the lower plot.)

How early would obesity have to have started increasing to falsify the idea that it’s caused by seed/vegetable oil? 1970? 1940? Earlier?

Now, when did people start gaining weight? This is tricky, because nobody was collecting BMI statistics back in the 1700s. But Kromlos and Brabec (2010) use a set of surveys taken between 1959 and 1994 and fit a regression to predict weight at age 50 from birth year. They then use this to extrapolate back to people born as early as 1882. (I think because someone born in 1882 would have been 77—and still hopefully alive—in 1959?) This gives this graph we saw earlier, with a long-term trend of people at the median gaining around 0.05 BMI/year:

While it looks like people were getting heavier back in the 1880s, I emphasize that the evidence is very weak: The leftmost part of the plot is an estimate for men born in 1882 in 1932 (when they were 50) based on data collected in 1959.

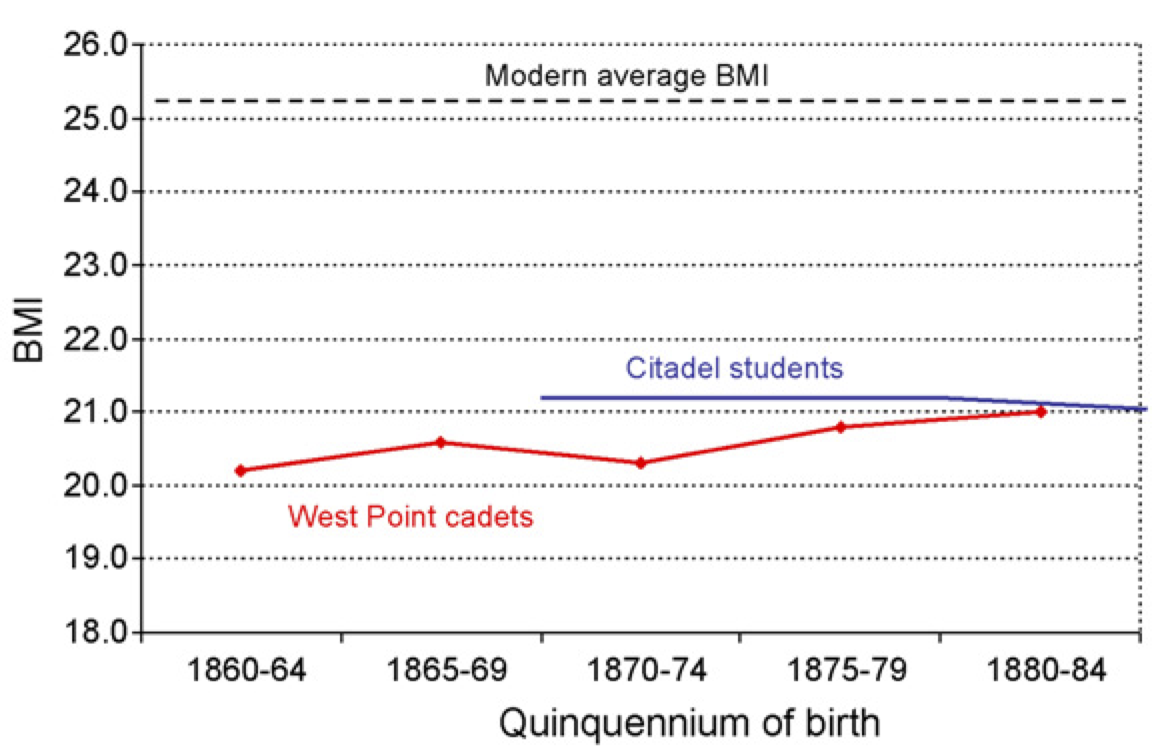

There’s also data for the incoming classes at a couple military academies. Hiermeyer (2010) collects data for people entering West Point and the Citadel:

Maybe West Point cadets got a little heavier? There’s a 20 year run, so at 0.05 BMI/year we’d only expect an increase of 1 BMI, close to what’s observed. But for the Citadel, if anything is decreasing. Coclanis and Komlos (1997) give more Citadel data, stratified by the age of the students:

| Birth Decade | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1870s | 19.5 | 20.0 | 20.2 | 20.2 | - | - |

| 1880s | 19.0 | 19.6 | 20.4 | 20.2 | 20.4 | - |

| 1890s | 20.2 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 19.9 | 20.1 | 20.0 |

| 1900s | 19.1 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 20.5 | 20.5 | - |

| 1920s | 22.1 | 21.2 | 21.4 | 21.8 | 22.3 | 23.0 |

| 1930s | - | 21.6 | 21.9 | 22.3 | 22.8 | 23.6 |

Again, it looks like not much changed between those born in the 1870s and the 1900s. But things started to pick up for those born in the 1920s.

All this data suggest people starting getting heavier during the 1920s or even earlier, when seed oil consumption was still very low. So I see this as some evidence against seed oil theory.

Of course, none of this data is very good. Surely there’s more long-term data on weight lurking out there somewhere? Typically, seed oil theorists point at data only going back to 1970 or so, but that will never prove anything, since obesity was already increasing at that time. We need to go back further.

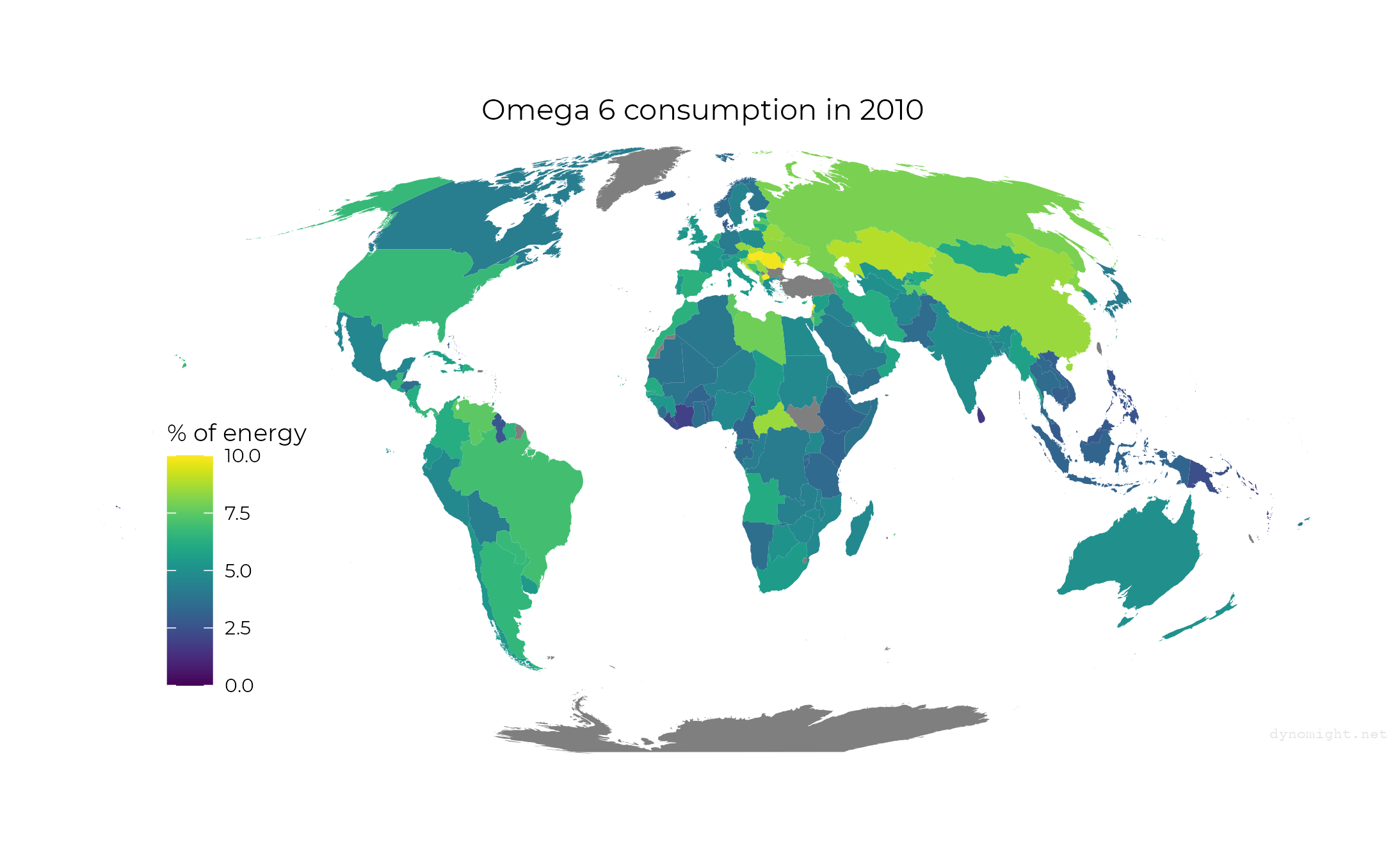

Omega-6 doesn’t explain inter-country obesity.

People in different countries eat different amounts of seed oil. If eating seed oil makes you fat, then must per-country seed oil consumption correlate with per-country obesity?

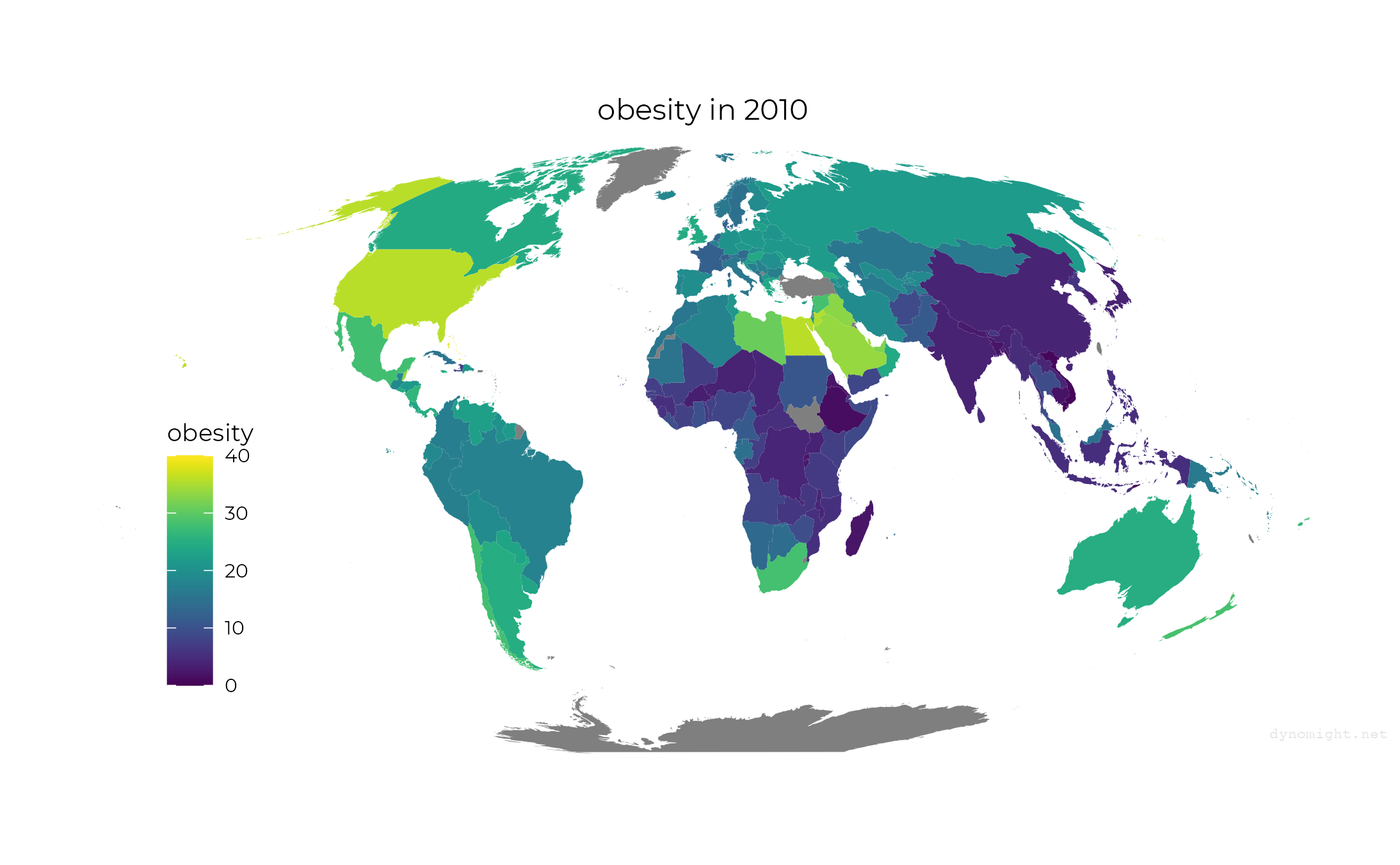

Not necessarily, no. But I decided to check anyway. I found the WHO provides some amazing data for obesity—the estimated fraction of the population that has a BMI of at least 30 by year. Here’s what that looked like in 2010.

(There’s no data for South Sudan because it didn’t exist in 2010. There’s no data for Antarctica because all the people there are penguins. I think there’s no data for Greenland/French Guiana because they’re considered part of Denmark/France. There’s no data for Taiwan because the WHO is afraid of China. I don’t know the deal with Turkey and Kosovo.)

The USA isn’t quite #1—It’s beaten by Egypt, the Bahamas, Kuwait, and a bunch of tiny island nations. American Samoa is way ahead at 71.63%.

Anyway, seed oil consumption data is harder to find, but Micha et al. (2014) give estimates for 2010. Here’s estimated omega-6 consumption:

Can you see a relationship with obesity? I couldn’t, so I made a scatterplot with one circle per country. (Click to zoom in and see country codes.)

Is anything there? Maybe so, I’m not sure. I did the same for saturated fat and all fat, which look about equally convincing. But if you put per-capita GDP on the x-axis…

Could it be that something else is going on here?

On distraction

A weak version of seed oil theory is that seed oils are highly processed, so why not use cold-pressed olive oil instead? If that’s the theory, fine. In fact, this is mostly what I do myself. I figure it might be useless, but it’s unlikely to be harmful, and olive oil is delicious.

And I wouldn’t be shocked if one of the suggested mechanisms for seed oil turns out to be valid. I wouldn’t be surprised at all if some mechanism turned out to be part of a larger, more complicated story.

And in practice, avoiding seed oils is probably really good for you, because it forces you to eliminate most of the processed crap you shouldn’t be eating anyway.

A middle-strength theory would be that seed oils might be harmful, so it’s safest to reduce seed oils and replace them with saturated fat. I disagree with this, because the balance of evidence says that saturated fat is more risky than unsaturated fat (monounsaturated or polyunsaturated). But I guess it’s not totally crazy.

But seed oil theorists mostly seem to push a much stronger theory: We know that seed oils are the cause of Western disease.

I’ll just be honest. I think this view is completely indefensible. I feel embarrassed when I see people promoting it. You’re sure? How? I don’t see any way to get to this conclusion other than heavily filtering the evidence—ignoring the flaws in everything that supports a predetermined view while scrambling to find flaws in everything that contradicts it.

Again, I’m sure you can send me long lists of random citations. (You don’t need to send them; it’s OK; I’ve seen them already.) But for anything that’s been studied in detail, there’s always lots of evidence to support any semi-plausible view. Do you have any idea how much evidence people can produce for UFOs or chronic Lyme or colloidal silver?

My real worry about seed oil theory is that it’s a distraction. If you want to be healthier, we know ways you can change your diet that will help: Increase your overall diet “quality”. Eat lots of fruits and vegetables. Avoid processed food. Especially avoid processed meats. Eat food with low caloric density. Avoid added sugar. Avoid alcohol. Avoid processed food.

I know this is hard. You could even argue it’s unrealistic. That wouldn’t make it wrong.

Look, I wish strong seed oil theory were true. That would be great. All we’d have to do is reformulate our Cheetos with different oil, and then we could go on merrily eating Cheetos. Western diet without Western disease! Sadly, I think this is very unlikely.

A cooked food could technically be called a processed food but I don't think that adds much meaningful confusion. I would say the same about soaking something in water.

Olives can be made edible by soaking them in water. If they're made edible by soaking in a salty brine (an isolated component that can be found in whole foods in more suitable quantities) then they're generally less healthy.

Local populations might adapt by finding things that can be heavily processed into edible foods which can allow them to survive, but these foods aren't necessarily ones which would be considered healthy in a wider context.